Put your hands at your sides.

Stand straight, shoulders back, tummies relaxed.

Keep your mouth slightly open to allow you to breathe.

Lower your eyes.

Breathe normally and focus on the feeling of the breath coming in and going out.

We will brush our brains for one minute or up to 60 counts once I ring the bell.

And our brain brushing begins now…

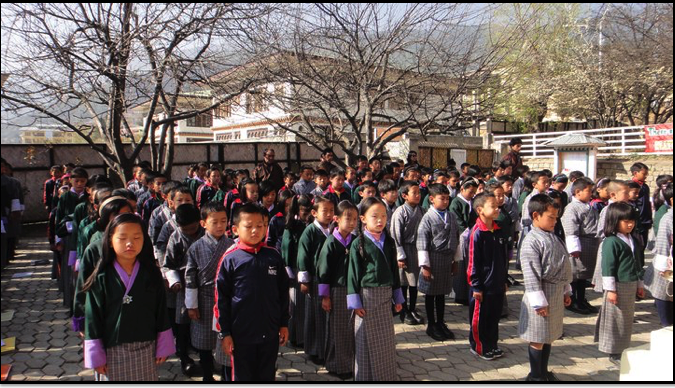

A few years ago, I taught in Bhutan for a few years, and this was how my school day began and ended, with a minute or so of daily meditating, brain brushing, mindfulness. Indeed, as a way to bring Bhutan’s principles of Gross National Happiness into everyday life, all students in all schools, public or private, meditate twice a day; once in the morning just before classes start, and again in the afternoon, just after classes finish.

At the primary school where I worked, we called it “brain brushing” — a term coined by the American U.C.L.A.-based professor of psychiatry, Dr. Dan Siegel — since comparing meditating to brushing one’s teeth made it easier for the younger students to understand the point of standing silently “doing nothing,” as a few kids liked to put it. Along with explaining the similarities between “mental hygiene” and “dental hygiene,” Early Learning Centre’s founder, Deki Choden, liked to emphasize that meditating allows us “to focus on all that we learn at school and be mindful in whatever we say and do.” For me, then, meditating and mindfulness are inextricably linked, with the former helping the latter to be that much more possible.

Our daily sessions lasted between one and two minutes, depending on how long the leader of the session, usually a sixth-grader, wanted them to be; during the warmer months, they were generally longer. When the bell rang signaling the start of our brain brushing, I found myself savoring the silence, stillness, and, despite being in a courtyard with close to a hundred students, solitude. In the quiet, by focusing on my “breathing in and breathing out,” as I looked down and stared at a cobblestone, everything else faded away; my breathing was all that I was.

At first, however, I fought this intense focusing. I didn’t enjoy losing full awareness of my surroundings, my thoughts, and my body, since I felt that my body, my thoughts, and my surroundings were what largely defined me. This zoning in had me zoning out and — being something of a control freak — I didn’t like feeling this loss of control.

Still, I stuck with it. Partly, I was curious to see where this meditating would take me. But even as I began to be one with my breathing, I could feel myself going somewhere else, to a kind of blankness, where thoughts and worries didn’t ricochet about because there was no room for thoughts and worries, just my breathing. I wasn’t me anymore, but I didn’t mind it. For quite quickly — by which I mean after just a few days of twice-a-day, minutes-long sessions — I relished being there, coming to see it as “my place.”

It’s not that my responsibilities melted away. I still had lessons to prepare, classes to teach, meetings to attend, calls, emails, and texts to make. It’s that their pressing urgency didn’t matter, didn’t apply, didn’t exist right then. Within this calmness, this respite, I could sense my heart not beating so fast, my lungs not breathing so hard, my body not bracing itself so rigidly against the day. It wasn’t “doing nothing,” as much as being nothing. When the session-ending bell rang, just as I had been aware of my breathing, when I returned to the courtyard, I found myself quite aware of an array of things, such as the breeze across my face, the sound of the birds in the trees, the warmth of the sun.

Students and teachers at Early Learning Centre could have extra meditation time during the day if they wanted. And so my fifth graders, classes 5A and 5B, would occasionally request them, and regularly did so in the run-up to tests. I occasionally asked my students what they liked about meditating, and after they had joked that it took up class time — of course, it did do that — they relayed how it helped them feel relaxed. And how about mindfulness? That wasn’t so clear-cut for them, or, really, for me.

We talked about how being aware of something could prove to be the first step towards being mindful of it. For instance, since I mentioned that I felt more aware of the birds in the trees whenever we finished meditating in the morning, one student, Sonam, suggested that I could and should take it further, and be mindful of birds, and trees, and nature in general. Thinking about meditation and mindfulness in that way prompted us to consider how being aware of our breathing could then get us to be mindful of our lungs and, by extension, our health in general.

And from there, being mindful of everyone else’s health? It felt logical, but also a bit of a leap, and something of a stretch. A kind of variation on, “Think globally, act locally?” If everyone were to take care of themselves, then everyone would be taken care of? Or, perhaps, an inverse of the so-called Golden Rule? Treat yourself, as you would like everyone else to treat themselves?

One way Early Learning Centre tried to answer that question, tried to make that leap from self-awareness to being mindful of others, was through “The Kind & Wise Way,” an empathy awareness class that I also taught. During the semester-long, twice-a-week class, third graders sorted out and carried out weekly acts of kindness, so that such acts would become a welcomed regular part of their lives, rather than regarded as unusual or un-cool. As for who and what would benefit from their acts of kindness, my two sections of kids came up with the categories of friends, family, animals, nature, poor people, and teachers, and they enjoyed reporting back that helping — by way of, say, writing a kind note, running an errand, picking up garbage, donating clothes — made them feel good about themselves and those that they helped.

Even so, they could be incredibly rambunctious. Granted, they were third graders, and third graders anywhere can be boisterous. Still, when I made clear they needed to behave in class (as well as in their other classes; as I said, they were rowdy), their response caught me up short.

“But, Sir Ivor, we are Buddhists, and we are like this because of our past lives,” their ringleader told me. “We can’t help it. It’s karma.”

With their smiles letting on that they were kidding (or at least semi-kidding), I told them that while I didn’t know a lot about Buddhism, I had a feeling their religion allowed for self-improvement, or at least self-restraint. When they rejected my points with laughter, I went on to say that they could then regard being quiet and respectful in class as an act of kindness towards me, their teacher, one of their chosen categories. I had them there, at least for the next few classes. In addition, I also confirmed that Buddhism does in fact allow for bettering one’s self. As one colleague told me, “Buddha teaches that the wise master themselves.”

The elementary school in the suburbs of New York City where I currently work as a substitute teacher has a mindfulness instructor visit every month to briefly discuss mindfulness and partake in meditation with the students. Not surprisingly, compared to the students at Early Learning Centre, mindfulness and meditation remain somewhat abstract and unknown, if not a novelty. Still, they enjoy the sessions, so much so that some fifth graders recently asked that we meditate just after they’d come back from lunch.

Getting them to settle into silence at their desks proved to be, also no surprise, a challenge. But just like with my fifth graders — my “fives” — at Early Learning Centre, we got there eventually, and I enjoyed feeling a little like I was back in Bhutan. Still, a classroom is not a courtyard, and intermittent meditation is not the same as meditation every day, twice over. But with the books put away, the lights dimmed, and the students hushed, I could begin to sense the calmness. Then, about two-thirds through, breaking the stillness, the class joker loudly whispered, “Mr. Hanson, I am seeing my future!” to which I quickly shot back, “Is it the Vice Principal’s office?”

Not only was I back in Bhutan, I was once more in my “Kind & Wise” class. That said, I did feel we were making some progress, in that plenty of his classmates made clear they did not want their meditating to end. As one student put it, “I am really liking breathing!”

Ivor Hanson is the author of Life on the Ledge: Reflections of a New York City Window Cleaner.

Leave a Reply