In 2009 I lost my career to an off-shoring deal: my entire department had been laid off, a department that numbered in the hundreds of people. Our jobs were sent to Asia. We trained our replacements, packed our boxes, and then we went home.

In the long months (and years) which followed, I was mostly shocked, paralyzed. I felt like the whole world was falling away from me, like a scaffold falling away from an unstable pile of brick. Having lost my status and income, I found myself increasingly on the margins. I was now surplus, like an extra, milling about the set of a film in which I no longer had a role.

With my camera I looked for subjects that were attuned to my alienation, to my sense of having been forsaken, abandoned, to being lost among the ruins.

I didn’t lack for material.

This is how The Recovery looked to me.

There wasn’t much to advertise in the Winter of 2010. No one was buying, no one was hiring. The system was down. An alternative title for this might be “No Options.”

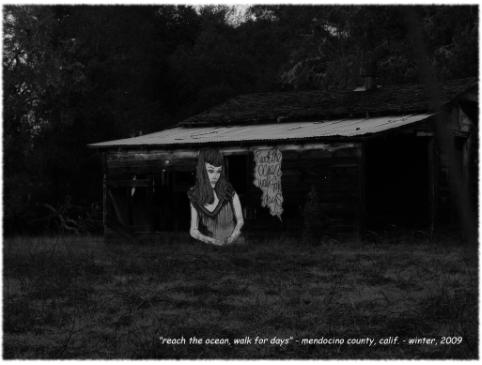

Next to what looks like an old cabin that would be right at home in a Civil War-era photo, someone had erected a standee of a woman with text alongside reading, “Reach the Ocean, Walk for Days.” I found this compelling, fascinating. Who had erected such a thing and why? To reach the ocean and walk for days, alone and solitary, wandering, lost, was the most compelling thing I could have imagined. There was a sense of solidarity in this, a sense that I wasn’t so alone, a negation of alienation in an image that reeked of it.

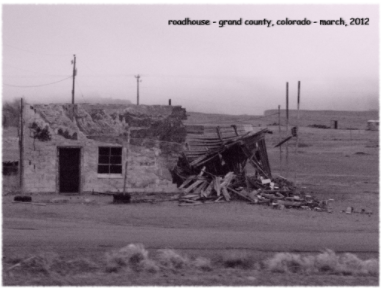

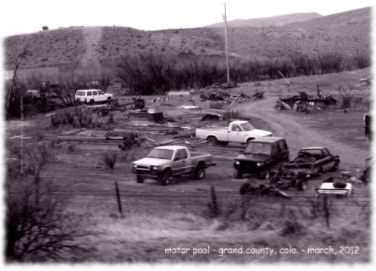

These two images were taken within a few miles of each other, from the window of a moving train, somewhere in Grand County, Colorado. Having moved in with a friend, still jobless after three years’ time, I was on my way for a long visit with my mother. The “roadhouse” itself astonished me, having a distinctly “Dust Bowl” quality about it. The graininess and bleakness and collapsed building could easily have been found in a photograph from 1931.

Although the Motor Pool vehicles were stationary and unmoving, they appear to be like angry bees, circling, furious and ready to tear into each other. The Dust Bowl feeling depicts the alienation of forgotten rural America, as well as juxtaposing the relatively contemporary appearance of the vehicles with the implied poverty of the Great Depression.

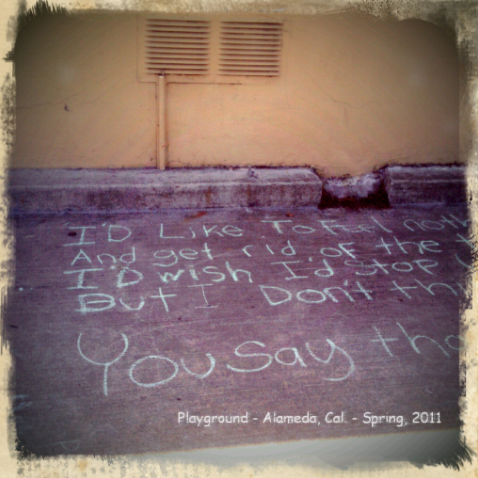

Sometime in the Spring of 2011, I passed a playground on my morning walk and found this message written in chalk. Here, in the midst of the Long and Never Ending Downturn, a person wishing s/he felt nothing nakedly wrote his/her heart on the pavement, perhaps unwittingly expressing the angst of so many forgotten, left behind as the “Recovery” gathered steam.

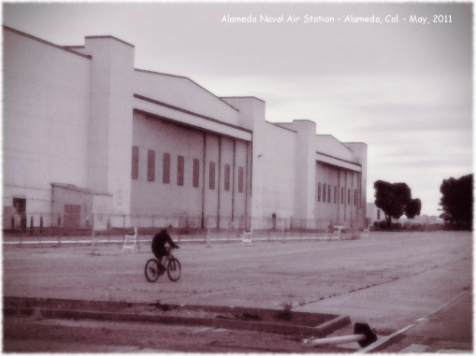

I began venturing onto the abandoned military base in Alameda, fascinated by the ruins of Empire. Having stopped for a moment near the aircraft maintenance hangers, I turned and saw a man riding his bicycle across the former tarmac, where fighter jets had once taxied on their way to and from the hangers and aircraft carriers. I found this compelling, because the bicycle is old, pre-flight technology. The man is grounded, stuck to the Earth and riding among the ruins.

And the Wright Brothers had been bicycle mechanics before their trip to Kitty Hawk.

Travelling to Colorado by train, I passed this queue of people lined up for holiday food at the Stockton Food Bank. The framing of the image makes me feel as if the people are falling through its borders, as they are indeed falling through the margins of society. The poverty in this image easily equals anything I’d seen on a trip to Latin America in 2012. This is a scene of the American Favela.

On a supply run from our own encampment, I found this neat lineup in the alley behind the enormous supercenter. I was intrigued, not only by the poverty and desperation of fellow exiles living behind Walmart, but also by the air of domesticity (bicycles neatly racked on the roof of the ancient RV, travel van parked neatly in front, etc.). The neat placement and descending lines, from the cargo truck to the two smaller vehicles, suggested camouflage to me.

This family stayed in place for several months. I passed by regularly throughout the autumn, as the Presidential Campaign lurched on. After the election, the family moved on.

The spot is now vacant.

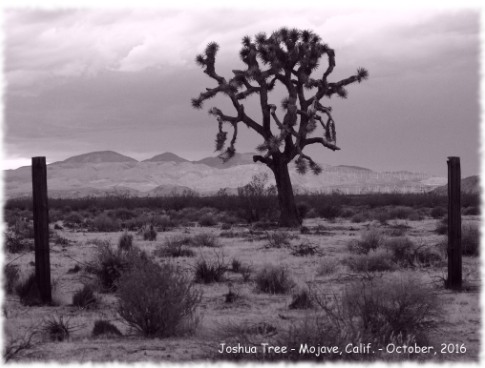

The Mojave Desert is the driest, most arid desert in North America. Joshua trees, native to the Mojave, thrive in this environment. With little water and often bad weather, these weird hybrid trees live for decades in defiance of their environment.

The Joshua tree has become something more to me than just the title of a decent album from my youth. The tree symbolizes hope, strength, and survival against the odds in a harsh and hostile climate.

Leave a Reply