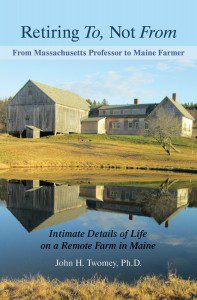

Photos courtesy John Twomey

In 1988, I began teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. Late in the day I’d pass through a grove of white pines to my building’s parking lot. Often I’d see a man watching the small pond across the road, where graceful birds danced and dove in the air. One day we fell into an easy silence, watching together. “Tree swallows,” he said. It turned out he had made and installed their wooden houses on poles. He kept count of breeding pairs, eggs, and fledglings.

John Twomey had been teaching there for several years. His still, intent way seemed unusual, more like a hunter than a professor. Our first conversations were about the pond, and the life it sponsored.

John welcomed me to the university, and we began a quiet twenty-year conversation about the nature around us. We were glad to be in different departments, he in Spanish, I in English. We could leave work matters on the other side of the pine grove.

John expressed his sorrow at having seen the Connecticut farmland of his early days cut into suburbs. He was set on doing something, at any scale he could, about habitat destruction. He had a long-term plan for after retirement. Did he ever.

John and his partner, Leigh Norcott, moved up to the farm in 2009. They manage the land for wildlife, grow their food, chop their wood, and feed the birds from their hands.

When I met him, I thought his ecological awareness was unusual. As time passed I became aware of his longing for this life of good work and solitude among wild beings. He was pouring his love and care into public land (our campus), soaking in what he could amid cars and students.

For his children and grandchildren, he has invaded his own privacy and written a book about his life on the farm. It is filled with details about how to grow vegetables, fruit, chickens, and trout, how to preserve one’s food, and how not to crowd one’s wild neighbors. His book manifests his generous spirit.

The book is a practical guide which reveals a land ethic. While John refers to himself as a farmer, and his home as “the farm,” he never sells anything. He could, of course. He produces a surplus. But he keeps his project closer in scale, and spirit, to gardening.

If the guiding principle behind a farmer’s hard work isn’t to make a living, nor even to feed himself, what is?

The short answer: protection of all the living beings within his reach. His reach includes the 125 acres of the farm, and another 30 acres nearby.

Of course, before conservation can begin, decisions must be made about what to protect, and how. Then somebody must actually be there to nurture the land.

“I encourage the summer flowers,” John said to me, “—but also dandelion and violet for the early spring, then golden rod and asters for the fall and late fall. Another favorite of mine is called ‘sow thistle’—a little flower, not unlike the dandelion, but it blossoms in late summer through fall. For many years, I’ve gathered the seed heads and spread them to the twelve green patches, where now that flower is quite well established and is self-seeding. Wild bees love to feed on the blossoms and wild turkeys adore the buds prior to opening — they snap them off and gobble them down.”

In a talk John said, “nurturing was, and always has been, central to my life. Nurturing gave, and gives me, a sense of purpose, and a sense of direction.”

I always felt John’s mix of sensitivity and steel determination. I wonder whether others might sense his way of being-in-the-world if they listen to this radio interview he gave to the program “Maine Calling,” on May 8, 2017: http://mainepublic.org/post/retiring-farm

It’s a lively discussion, with host Jennifer Rooks, and callers who ask good questions. Even the station’s announcements seem to contribute to the community-within-nature discussion and energy.

John is a subtle man, and his passion sneaks up on you—maybe. Who can say what one friend sees in another?

In his book On Friendship, Alexander Nehamas describes a mystery. Suppose two people, A and B, know a third person, C, pretty well. A and B agree in all their judgements about C. They find him admirable and accomplished. Yet one of them, B, isn’t particularly interested in C. A, on the other hand, finds C fascinating, and values any time they spend together. Nehamas discusses various explanations for this, but when all is said there remains a mystery about the feeling between friends.

John is a good listener. People know that. Whether they perceive his awareness, or his joy, in the creatures around him, I don’t know. My question is whether he was born this way, or created himself from fortunate, or unfortunate, circumstances.

I asked John to tell me about his childhood, what encouraged or discouraged him, on his path.

Luke Wallin: When you were young, did you have mentors who were farmers or conservationists in the ways that you are now?

John Twomey: Yes… I observed the farming operations of two neighbors. Both seemed quite contented with their rural activities, both knew their land and animals well, and both truly cared about their land.

My mother lovingly encouraged my interest in gardening, raising chickens and pigeons, feeding wild birds, and hunting and fishing.

LW: Your passion for the natural world seems a lot like mine, which, emotionally, is still tied up with hunting. I don’t hunt now but thrill to seeing a nice buck, or a gobbler, or a woodcock overhead. Did you ever have that drive to hunt? You seem to have it for fishing.

JT: I most certainly did. Uncle Ed bought me a BB gun and turned me loose on the “mountain” at age seven -– hard to imagine in today’s world. All on my own I learned to stalk birds and other critters –- when to move and when to remain still –- and how to sit for long periods of time –- motionless!

I truly loved every minute of these experiences.

I spent hours and hours alone –- hunting, observing, silently taking in the ways of the creatures and the woods. To this day I find that that early wiring of my brain allows me to read wildlife and know how to move or not move around them, and it makes it possible for me to be completely at home in the woods.

In my sophomore year, a year when I was anything but a good student, I wrote an essay about waking up in my upstairs bedroom, coming downstairs, having coffee, and going rabbit hunting with my beagle. At that point in my life I tended to view myself as a country bumpkin and was somewhat inclined to hide my rural upbringing. Much to my surprise, Ms. Little wrote back that I was so fortunate to know what I knew about beagles, rabbits, hunting, and the outdoors. I remember that positive feedback so well –- it was the first time I experienced someone thinking that there was some value in what I was doing –- aside from putting meat on the table.

I did not have a great relationship with my father, a man with an unpredictable temper and rather strong propensity toward physical violence and verbal abuse. While he would spend weekend afternoons watching sports on TV, I would retreat to the forest and the wild creatures I had come to know so well.

LW: You extend the gift of solitude to the creatures, as well.

JT: I’m interested in how things are going in these secluded locations but rely mainly on tracks in the snow, such as those of fishers and bobcats, to inform me on the comings and goings of those who frequent these particularly quiet spots. I do find the information I glean from tracks to be quite enough — I’m happy to speculate on what good things are going on once they get into the areas where we do not venture.

LW: Your emotions seem to be about the creatures—rather than the “farming” focus of your book.

JT: You are absolutely right. I did have an early inclination to garden, and began gardening on my own around the age of eight.

But it is the wildlife and wildlife habitat that are the heart and soul of what I do on the farm. Fortunately, once again, Leigh feels exactly the same way. Being around relatively undisturbed wild creatures meets some sort of a need deep within me.

I never tire of watching critters like deer, turkeys, squirrels, and small birds. To see a fox, coyote, or bobcat hunt is a special treat. While watching them I absorb their movements and reactions –- I feel as if I’m gaining an understanding of their inner needs. Spending time now working on wildlife habitat is, I believe, sort of a way of repaying nature for all it did for me at a critical point in my life.

Retiring To: Not From, may be ordered at http://johnhtwomey.com.

#

Just today on August 15, 2021 I ventured to visit with John and Leigh. We walked through field after field while John explained how he managed the farm for wildlifes benefit. And he has so many heirloom apples grafted onto his wild apple trees! Now he is raising Speckled Sussex heirloom chickens. So delightful!