This essay is based closely on the original version, first published in BAILE ’98, the Journal of the Geographic Society at University College Dublin. It reports on an adventure Luke had as part of a Regional Planning team working to protect the Connecticut River in Massachusetts. The story is reprinted in High Horse!, Fleur de Lis Press, Fall 2004, an anthology of work by the faculty of the Spalding University MFA in Writing Program, and in Luke’s 2006 book Conservation Writing: Essays at the Crossroads of Nature and Culture.

The version here is updated in 2017 for Sisyphus. There are a few corrections added to the text. All the paintings are by Luke Wallin. Following the essay, there is a section of links and updates on some of the participants in the project, and on what has happened to the river over the past 30 years. The news is mostly good.

We slip our canoes into the Connecticut as clouds of spirit-mist rise from its cool surface. We’re just below Turners Falls dam, near the Massachusetts-Vermont line, and this surface fog seems strangely alive. The Indians once saw in these whitish movements the ghostly residents of a place, and this morning as we slide past sandbar willows out into the current and breeze, that vision feels true.

This site — Peskeompscut, to the local Potumtucks — was the scene of a terrible massacre in 1676. English colonials surprised sleeping villagers and destroyed 100 people: children and “many old men and women.” Another 140 died leaping over the falls, or when their attackers followed along the shore and shot them as they swam. I wonder whether these souls are among the spirits rising from the river’s silvery surface on this perfect fall morning.

There are ten of us in four canoes. Nine are members of a University of Massachusetts Amherst team charged with preservation strategy and tactics. The tenth is our leader, Terry Blunt, a trim, quiet intense man of about 35. Terry is a senior planner for the Commonwealth, and his first lesson to us was about language.

“Don’t use the word ‘preservation’,” he said. “It makes people mad. More than mad, furious. ‘Conservation’ is all right, but the best word is ‘protection’.”

We have taken this deeply to heart. We are to formulate a plan for our study area, Reach II of the Connecticut River in Massachusetts, stretching from the Vermont line down to of the town of Northampton. It is the last free-flowing section of the river within the Commonwealth, and Terry wants to safeguard its quiet values before the region’s development craze overwhelms them.

We make good speed over the water, and our bowman, John Bennett, maneuvers us closer to Terry’s canoe to hear his soft commentary. Terry is pointing high above us, upriver in the sunlight. Just a few years ago the river was terribly polluted and all the osprey had vanished. But new laws have brought better waste treatment plants to the river and the osprey have heard the news; they’ve returned in healthy numbers and become a symbol of valley pride.

Terry indicates a pipe protruding from a high bank, streaming liquid down into the current. “That’s why I’m here,” John Bennett says to me as we paddle past. John is a powerful young man in his mid-twenties; he is handsome, self-contained and practical. “I was working for the state as an inspector. I’d visit all these plants and they’d show me how they’d sealed off their pipes. They’d claim they were doing proper disposal, not dumping anymore. But you could look at the valves and tell they were lying. You could look in their eyes and tell. I knew it and they knew I knew.”

Terry motions us over to the east bank, where we hold all four canoes together, bobbing, as he shows us a deposit of thick blue clay. “The old Indians liked this,” he says, “it works beautifully in pots.” And then he gives us another warning: “Please don’t anybody tell where this vein lies. We don’t need people digging out the side of the bank, undercutting the ledge.”

I look up to tall maples and oaks in fall colors, and at the steep eroded slope laced with poison ivy. It is amazing that people would destroy this bank, that we must hold the secret of the blue clay.

For the past few years I’ve researched and written books involving endangered species and Native American culture. The aim of my books has been art, not action. Joining this project has given me a sense of how people can combine skills in conservation work and make things happen. But the first lessons, it seems, are restraint, study, care, and silence.

The man in the middle of my canoe is Chris Ryan. He learned to make maps in the army, and now produces limited editions for conservation groups. His work is first-rate, and I have proposed to him that we collaborate on a book which would identify all the ancient tribal territories in Massachusetts, and provide maps and directions to each. When the traveler arrives, there will be a local path to a special place — an overlook, a grove, a waterfall. We would choose each spot by our sense of sacred place, and give the visitor a chance to experience what the old tribes might have most appreciated.

Toward this end, as well as the Reach II project, I’ve been visiting with Bob Paynter, archaeologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He’s been considering my request for site information.

But he has given me second thoughts with a story. There’s a man in Greenfield, Massachusetts, who specializes in looting Indian graves and middens. He absorbs the rumors of a new discovery, and he’ll bore like a coal miner, like a human mole. Once he went underground from a neighbor’s property, and tunneled all the way into an incredible site. He looted it, broke pots, took the bones of the dead. This man is the link between an international artifact-trading network, and the places we want to protect.

And especially since Lady Bird Johnson, first lady to President Lyndon Johnson, held a White House conference on Scenic Beauty back in 1969, planners have been able to articulate vistas like this one as common property “visual resources,” in Emerson’s sense. There are systems of comparison, rank-ordering, quantification.

As the canoes bob in the current and Terry reminds us of our vow of silence about the vein of blue clay, I wonder whether the sacred-places book would only invite the least spiritual among us. For that matter, will our efforts at a protection plan only draw more visitors to this fragile river?

But when we slide into the current again, and the wind picks up, clean fresh air drives some of my doubts away. Whether it’s negative ions or benevolent spirits, I believe in our mission.

We paddle in a long, lazy curve and the banks are timbered with thick beeches and maples. Straight, impressive hemlocks rise in a shadow-dark wall atop the bluff. There is no clear sign of humanity, of farming or building, though we have learned this wildness is an illusion.

The entire valley has been intensely farmed for centuries, and now only a narrow band of forest graces the banks. But these enclosing trees and bluffs give a sense of timeless peace.

It is a quality we will claim in our report as a rare cultural memory: we are experiencing what New England river valleys were like five hundred years ago.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, writing in 1835, declared that Smith and Jones may own their farms, but the view encompassing each of them belongs to everyone. And since Lyndon Johnson held a White House conference on Scenic Beauty back in 1969, planners have been able to articulate vistas like this one as common property “visual resources,” in Emerson’s sense. There are systems of comparison, rank-ordering, quantification.

We come into sight of a pair of black cormorants, and watch them dive deep. The Dutch and Chinese trained these birds to retrieve fish from the sea, and ensured their return by placing brass rings around their necks. Only by returning could they earn an occasional fish, and be allowed to swallow. Such an old interaction between humans and birds brings to mind our mission. Our team is not outside the ecosystem of the river, far from it.

What we accomplish may determine the fate of these birds, certainly of the ospreys and bald eagles. This winding, riverine landscape is both a centuries-old, humanized site, a kind of grand public garden, and also a bit of wild nature in the midst of intense farming. I dip my fingers into the cold water as we shoot past the cormorants. A cluster of gray and white gulls bobs close to shore.

After an hour Terry motions for us to beach our canoes on a big sandbar up ahead, and soon we walk and stretch our backs. He instructs us to pull driftwood and stones into a rough circle. Once we are settled on these dry seats over the damp sand he shows us silver maples and a tall cottonwood on the bank. Here beside us grow limber saplings of sandbar cherry.

“Since the river cleanup, fish populations have become more stable,” Terry says. “All year you have walleye, channel cat, northern pike, small and largemouth bass, rainbow trout, pickerel, and anadromous (migrating) Atlantic salmon and short-nosed sturgeon. That last one’s on the federally endangered list, and there’s a $20,000 fine for possession.”

“Now the water flow is a big factor for all these fish, especially herring and shad, and especially during spawning. Large fluctuations can sweep away larvae and kill them through lack of oxygen. To keep things even, the Cabot Station hydro plant is required to release 1,430 cubic feet of water per second at all times.”

[I have learned that this is a tiny amount for a river the size of the Connecticut, and that the numbers of herring are way down.]

This information stuns me. It brings home how utterly dependent all this river life is upon constant human monitoring and care. We literally have the fate of Connecticut in our hands, and I hope some dial-watcher won’t nod off some lonely midnight.

Terry wants to limit powerboats to 10 miles per hour. This would give the shad better protection, and it’s the sort of regulation the six river towns might agree to. He says common sense would tell us this is a sound idea, yet he can’t get a biologist to testify seriously: there aren’t data, no way to get any.

The biologists, who met with us a few days ago, were chagrined by their professional codes. They didn’t want motors in the reach at all. They said they know oil and gas spills, and props, churn up the shallow bottom. What they don’t know is how to close the gap between their concern and their science.

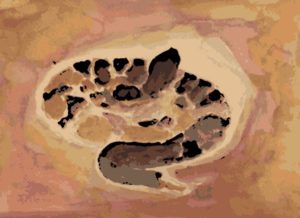

It is time for another secret. “Right up there,” Terry says, “is an endangered-species habitat. Whatever you do, don’t talk about this.” We are alert. “Crotalus horridus,” he says, “the timber rattlesnake.”

There are cries of, “Eeeww.”

“It seems strange,” he says, “but some folks would hunt them down, if they knew where to find them.”

“The old males turn almost black. They’re in demand in carnivals, and even for cowboy hatbands.”

We talk a while longer, then fall silent and listen to the river. It speaks strongly and softly, flowing within its frame of banks and timber, carrying its strange mixture of wildlife and culture. It seems a long time before Terry rises and says, “Well.” And I am beginning to feel a belonging here, even to these recent strangers. Our task together feels less important than our canoe trip, at least right now. This feeling, called the “river effect,” this sense of the possibility for quiet transit and learning, is precisely what we must protect.

Downstream we approach a site where Terry is on the brink of closing a deal to buy development rights. This is one of his — and our — most valuable preservation tools. Farmers who want to protect the scenic or wildlife or cultural values of their land, but who need cash and must face exaggerated land prices, can sell development rights but retain ownership. Many don’t know how this works, so publicizing the process is one of our tasks.

But we mustn’t tell anyone about the farm up ahead. Terry has been discussing the sale of development rights, and the farmer is most uncertain. Not only are negotiations at a delicate stage, but this river’s edge is a small, fragile ecotone of rare plants. And again, there are those who, if they knew, would steal and market them.

The more I learn of the threats, the more amazed I am at the river’s surviving richness, its wealth of life and history, its unspoiled timber and sandbars and long thin islands. Hedged in by the development boom in the valley, assaulted by looters, the river itself is coming to seem an island of sacred space.

I think of my friend Barry Greenbie, a professor of planning at the University who has an intriguing theory of cultural space. Barry canvassed decades of research on brain physiology, wondering whether this work could illuminate the human need for safe, comforting spaces. The ancient limbic system seems to require secure borders, nest sites, and memories. But the outer cortex, a later phenomenon, gives us abstract thought and projects our concepts, grids and schemes, onto global, impersonal space. Some cultures, such as the Japanese, recognize this and provide for dual spatial experience. They allow stability and comfort within the home and walled gardens, preserving tradition in this sphere, while encouraging innovation and change in the professional realm of global trade. Because the Japanese are so traditional, Barry contends, they are able to excel at the modern.

But when a culture represses this duality, the result is psychological disturbance; for example, densely crowded apartment buildings in the “international” style fail to give residents a clear inner/outer experience. As a result, there is no peace of mind for renewal, planning and creative struggle in the outside world.

It seems to me that Reach II of the Connecticut River is precisely a safe, bounded home territory for those valley residents whose working lives are spent amid increasing traffic, development, and competition. Perhaps an argument of this kind can be constructed within our project, perhaps not. But either way, this experience of the quiet river is a blessing. It may be natural habitat as well, for the ancient limbic brain.

We pass the spectacular Sunderland Cascades, huge water-worn boulders on the river’s east bank, across which thin, glassy sheets of spring water pour. This is another site targeted for special protection, another in-process deal of which we team members must not speak. We glide past in admiration, and soon come into sight of our landing beneath the Sunderland bridge.

Our trip is over. There are good feelings as we drag the canoes up the muddy bank, and carry them to car top racks and pickup beds. I am tired as I wave goodbye to my new colleagues. My house is only one mile away, and in a few minutes I am home with my family, filled with images and sounds from the river.

My little boy, three-and-a-half, asks, “Did you save the river, Dad?”

I smile and meet his mother’s eyes. His question reminds me that conservation is a daily effort.

“We made a start.”

“Good,” he says.

I drive them back down the road to the water’s edge in the falling light, and we stand beside the empty landing. A bat skims narrowly past my head.

My responsibility is to write the section of our report on Native American “cultural resources.” And although Bob Paynter seems close to showing me the site files, he has almost begged me not to reveal where the arrowheads, pottery, and human bones lie.

I began this assignment eagerly, thinking the best argument for protection would be a clear designation of the values at risk, of what could be lost without strong action. But I know now that I’ll be writing for the looters of graves and rare plants, of blue clay and rattlesnakes, as well as for those with the will to preserve.

I must convey a sense of Reach II’s worth without compromising the choice locations, especially tribal sites. We must protect the graves; everywhere there is a storm of Indian demand for the return of ancestral remains. Many Native Americans say their ancestors’ ghosts will walk the landscape, restless and weary, until their bones are finally consecrated in the proper ground.

Standing by the dark, gurgling river with my family, I believe I hear what the mist-spirits were telling me this morning. It is something to know the ancient riverside camps and middens and graves. These, Bob Paynter will tell me in time. He will unlock a dusty, unused room and show me the eyes-only site files. Some will indeed reveal sacred places, and if I visited them I would feel those spirits, even now. But such secrets have no place in my report, nor in a guidebook of maps. I must take up, this time, the path of silence.

[The six river towns voted our protection plan into their zoning codes, giving it the status of law.]

River of Silence Updates, September 2017

John Bennett, who was in my canoe that day, works for the Windham Regional Commission in Brattleboro VT. He is still active in the issue of erosion along the Connecticut River above the Turners Falls Dam as a member of the Franklin Conservation District.

The entire watershed became the Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife Refuge in 1997. I’m pretty sure it’s the only Refuge that contains an entire watershed, complete with all the people living in it. You can read more about it at https://www.fws.gov/refuge/silvio_o_conte/

The Connecticut River was named an “American Heritage River” in 1998 by the Bill Clinton administration.

The Connecticut River was named the first, and then only, American Blueway, under the Obama administration in 2012. See https://www.fws.gov/northeast/ctblueway.html.

The Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant closed down at the end of 2014. The plant heated huge volumes of the river, and so the closing greatly affected the river all the way down to Holyoke. That winter, the river in the northern stretch of Massachusetts reached 32 degrees F and froze over for the first time in decades.

The Connecticut River Conservancy has been conducting bacteria testing in the river and can see that the river mostly meets water quality standards for swimming, except after large storm events. Results are posted at www.connecticutriver.us under the “Is it Clean?” page.

In general, thanks to the Clean Water Act, the river has been gradually getting cleaner. Still, there are problems and threats.

The Turners Falls Dam and Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage plant is currently in the process of being relicensed through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The new license will cover all operational and mitigation requirements that will be in place for the next 30-50 years. Stakeholders are actively involved in getting a better deal for the river, one that improves fish passage, flows in the river, improves water quality, reduces erosion, and provides for new and improved recreational amenities.

Numbers of migratory fish have been counted at Holyoke Dam every year. See numbers online at https://www.fws.gov/r5crc/migratory_fish_counts.html

A good source of information for Native American interests in the Turners Falls area is the Nolumbeka Project. See https://nolumbekaproject.org/

Many thanks, for information and perspective, to Andrea Donlon, River Steward with the Connecticut River Conservancy, formerly Connecticut River Watershed Council, 15 Bank Row | Greenfield, MA 01301 | www.ctriver.org

I was saddened to learn of team leader Terry Blunt’s passing. He was ideal for our mission—patient, kind, and with a will of iron. He went on to protect land in the valley throughout his career. Terry Blunt’s obituary contains this:

Blunt said in 2006, “Land is like a child, it really can’t defend itself.” He said that if land was not protected, “it could otherwise turn into housing lots or cell towers.”

Robert D. Yaro (President Emeritus and Senior Advisor, Regional Plan Association) was the UMass Amherst professor of planning who supervised our project. He was wonderful to work with.

For more than 40 years, Bob Yaro has been a practitioner and thought leader in urban, transportation and environmental planning in the U.S. and around the world. Yaro served as president of RPA from 2001-2014 and has been part of the organization’s leadership for more than a quarter century.

He led development of and co-wrote RPA’s third regional plan, “A Region at Risk,” and initiated the organization’s fourth regional plan in 2013. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, he convened the Civic Alliance to Rebuild Downtown New York, a broad coalition of civic groups that helped plan the rebuilding of the World Trade Center and Lower Manhattan.

This document, for sale on Amazon, contains our report on the river.

Thanks to Charles Entrekin, old friend and publisher of Sisyphus, for suggesting this update and visuals.

Leave a Reply