Charlottesville, VA 2017

History, despite its wrenching pain,

Cannot be unlived, but if faced

With courage, need not be lived again.

Maya Angelou, On the Pulse of Morning

“In Charlottesville on Saturday [August 12, 2017], as militarized groups of neo-Nazis, the Ku Klux Klan, and white nationalists gathered in Emancipation Park around the statue of Robert E. Lee [because the Charlottesville government was planning on removing the monument], clashes broke out between the white supremacists and counter protesters. Social justice activist Heather Heyer was killed and many others were injured while marching peacefully that day, when a purported neo-Nazi sympathizer allegedly plowed a car into a crowd of counter-protesters.” Bill Gainer, Dartmouth News

Before I listened to a Southern man being interviewed on CNBC, I hadn’t thought much about the statues. But as I listened to the interviewee, I thought what the person was saying was what I might say if I had been interviewed. For the first time, I confronted what I thought these Confederate monuments represented.

I was born and raised in Birmingham, Alabama, but my roots in the south are shallow. My maternal grandmother came over from England as a child.

The Southern sentiment is that the Civil War was about states’ rights more than about slavery. The interviewee was reiterating ideologies that I had heard my whole life about the Confederate generals being “upstanding and honorable” and Union generals being amoral degenerates, about the North being “just as oppressive” as the South.

This mentality was not considered extremist. It was “normal,” like the weather. We breathed it in. The re-visioning of history had been cultivated for a hundred years, after all. Politico offers the following insights from Joshua Zeitz:

“Confederate organizations—particularly the United Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, whose local chapters funded and organized the construction of many of the monuments that are now in contention—de-emphasized the ideological origins of the war and instead promoted a powerful but vague cult of Southern chivalry, battlefield valor, and regional pride. They recast the war as a battle over the principle of states’ rights and Southern honor…

’Whatever else I may forget,’ the ex-slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass said in 1894, ‘I shall never forget the difference between those who fought for liberty and those who fought for slavery.’ Douglass … deplored an emerging national consensus that the Civil War had been fought over vague philosophical disagreements about federalism and states’ rights, but not over the core issue of slavery…

As long as we continue to perpetuate the myth of Confederate innocence—the idea that good men on both sides fought over distant abstractions and then came together again in brotherhood—we continue to lie to ourselves. If just removing statues and icons doesn’t force a change in outlook, venerating and fetishizing them, and refusing to be honest about their meaning, almost ensures that the country won’t fully confront its past.”

48% of the United States population still believe that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights. Only 38% believe that the war was because of slavery. But the Confederacy was based on protecting the institution of slavery, as evidenced by its own founding documents. In addition, Robert E. Lee wrote of an 1866 proposal, “As regards the erection of such a monument as is contemplated, my conviction is, that however grateful it would be to the feelings of the South, the attempt in the present condition of the Country, would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating its accomplishment; [and] of continuing, if not adding to, the difficulties under which the Southern people labour.”

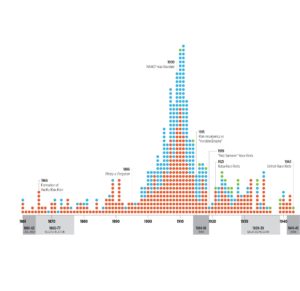

Through the Southern Poverty Law Center, I determined that there are more than 1500 Confederate monuments displayed in public places, in 31 states and the District of Columbia. That is 20 more states than were in the actual Confederacy. Though, granted, a number of these statues have been coming down in the past weeks, I wonder, why has it taken us so long? How much do the racial bigotry and racial bias of the American way of life contribute to that answer? What will it take now to relegate the monuments to the “dustbin of history?”

Southerners have been on the wrong side of history for a long time. A majority of Confederate monuments were erected in town squares and courthouses between 1890-1920, well after the Civil War but during the cementing of the Jim Crow laws. The monuments were and remain symbols of a failure on the part of the South to admit defeat. They offer a means to maintain the myth of Southern chivalry and white ownership of the South. A whitewashing of history. The statues memorialize a tyrannical, despotic way of controlling black people’s lives and turning them into chattel, instead of treating them as Americans, human beings who should be afforded equal rights. The statues represent the treasonous rebel leaders. They are also intended as intimidation – a clear message of who still controls the South. Capitalism and its insistence on profit and infinite growth became more important than human decency and morality.

In 1954, one hundred years after the Civil War, Brown v. Board of Education ignited the Civil Rights movement, and the South erupted in a new wave of racial antagonism. There was a second spate of Confederate monuments erected, this time on school and college campuses, reinforcing racial segregation by rewriting and memorializing history. Even then it didn’t sink in how divided the Southern black and white populations were.

In the mid-1960s, I took a job at Head Start, teaching in one of Birmingham’s black neighborhoods. I didn’t realize my father was going to be so upset. After all, these were just pre-school children. I was dumbfounded by his fury and judgment. It shook me to the core. My father and I almost came to physical blows and I realized I might be thrown out of the house. He hadn’t wanted me to attend college and we argued about that. My father perceived this educating of black children as my use of my education to enable more young black people to edge white people out of the job market. My uneducated father thought of job opportunities as a zero-sum game—there were only enough for your own people. It was a competition, there were winners and losers, and I had joined with the enemy by helping the wrong side. My father called me “a traitor to my race.” His perception of my “betrayal” of the family was the final break in our relationship.

I couldn’t understand why he embraced a racially-divided ideology. I don’t understand today why this is a national conversation we are still having.

It is interesting to consider who is paying attention to the monuments today. Recall that a majority of the monuments were erected in front of courthouses and government buildings during the Jim Crow era and places of education during the Civil Rights struggles. I believe they were erected with the intention to intimidate. That theory is reinforced by the make-up of the crowds who react to having them removed. NPR offered the following analyses in an article by Miles Parks on August 20, 2017:

“’Most of the people who were involved in erecting the monuments were not necessarily erecting a monument to the past,’ said Jane Dailey, an associate professor of history at the University of Chicago. ‘But were rather, erecting them toward a white supremacist future.’

James Grossman, the executive director of the American Historical Association, says that the increase in statues and monuments was clearly meant to send a message.

‘These statues were meant to create legitimate garb for white supremacy,’ Grossman said. ‘Why would you put a statue of Robert E. Lee or Stonewall Jackson in 1948 in Baltimore?’

‘Who erects a statue of former Confederate generals on the very heels of fighting and winning a war for democracy?’ writes Dailey, in a piece for HuffPost, referencing the just-ended World War II. ‘People who want to send a message to black veterans, the Supreme Court, and the president of the United States, that’s who.’”

I ask further why statues of Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney stood for 145 years in both Annapolis and Baltimore. Justice Taney handed down the decision universally considered by historians to be the Court’s worst ever to this day, only the second time that the Court considered an Act of Congress to be unconstitutional and an indirect catalyst of the Civil War. In 1857 Taney presided over Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred Scott and his wife Harriet were slaves who sued for their freedom after they were taken from the slave state of Missouri into territory where slavery had been prohibited. Justice Taney’s court ruling held that “a negro, whose ancestors were imported into [the U.S.], and sold as slaves,” whether enslaved or free, could not be an American citizen and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court. The ruling also stated that the federal government had no power to regulate slavery in the federal territories acquired after the creation of the United States. It was functionally superseded by the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted in 1868, which gave African Americans full citizenship.. And yet, the legislature of Maryland saw fit to erect a bronze statue in front of the Maryland State House in Annapolis in 1872 that was not finally removed until 2017 in the dead of night, a memorial to a man who wrote that black Americans could not be citizens and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The mayor of Baltimore also removed a second Taney statue (and three other Confederate monuments) under the cover of darkness.

In August 2017 William A. Bell, the mayor of Birmingham, Alabama, draped a Confederate memorial with plastic and surrounded it with plywood with the rationale, “This country should in no way tolerate the hatred that the KKK, neo-Nazis, fascists and other hate groups spew.” Immediately afterwards Alabama Attorney General, Steve Marshall, sued Bell and the city for violating a state law that prohibits the “relocation, removal, alteration, or other disturbance of any monument on public property that has been in place for 40 years or more.” It is still happening. It is time to acknowledge how statues are symbols, potent reinforcers of specific political ideologies.

As I mentioned, I never really gave these statues and monuments much thought. I am sure I walked by many of them. Now that I ponder their significance, I realize how much they represent. They are not just art. The symbolism in the bringing down of the statues of Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Saddam Hussein and Christopher Columbus is akin to the symbolism in the bringing down of the Berlin Wall. Germany destroyed all Nazi-related iconography. The Ukraine brought down all 1320 statues of Lenin. It’s time to take down our Confederate monuments because they are inappropriate in an inclusive society.

We can’t begin to heal if we haven’t acknowledged our history. We can’t ignore what has taken place if we have any hope to heal our culture. Bryan Stevenson (director of the Equal Justice Initiative) suggested that the North won the Civil War but the South won the narrative and the statues are part of that narrative of racial inequality. Avoiding honest conversation about this history has undermined our ability to build a nation where racial justice can be achieved.

Unfortunately, in his response to Charlottesville, the President has refused to acknowledge a unified nation. Donald Trump’s reaction to the protesting white supremacists, neo-Nazis, nativists and counter-protestors (making statements acknowledging blame on “many sides, many sides”) demonstrated his refusal to choose which side of this issue he was on, and offered a false equivalence.

His response is probably best summed up by Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone:

“Trump opened by blasting the ‘alt-left’ for coming to the rally ‘with clubs in their hands, swinging clubs.’ He then drifted into a freewheeling rant about the removal of statues of figures like Robert E. Lee. ‘George Washington was a slave-owner,’ he complained. ‘Are we going to take down statues to George Washington? How about Thomas Jefferson?’ He shook his head, adding, ‘You really do have to ask yourself: Where does it stop?’ He then pulled out a line that might have been straight from a Stormfront editorial. ‘You’re changing history, you’re changing culture,’ he said, hurling log after log on the bonfire of his credibility. Nothing like this had ever been seen before. It was the presidential equivalent of a run on the bank, an instant mass liquidation of political capital.

When it was done, stunned reporters watched as Trump retreated from view, presumably to plot his next mistake. The whole cycle was classic Trump: offend, deflect, reverse course, deny, counter-accuse, re-offend, re-ignite. Arguments about one set of remarks turn into interminable arguments about even worse sets of counter-remarks. Life in the Trump era is like the president’s favorite medium, Twitter: an endless scroll of half-connected little anger Chiclets rapidly spinning us all into madness and conflict, with no end in sight.

This is Trump’s legacy. Because of his total inability to concentrate or lead, he will likely never do anything meaningful with the real governmental power he possesses – if he had a tenth of the managerial skills of Hitler, we’d be in impossibly deep shit right now. But as an enabler of behavior, as a stoker of arguments and hardener of resentments, he has no equal. Under Trump, racists become more racist, the woke necessarily become more woke, and areas of compromise among all quickly dwindle and disappear. He has us arguing about things that weren’t even questions a few minutes ago, like, are Nazis bad?”

Now it is time for the country to wake up. Time for Congress to speak out. Time for the leaders of our country to speak to what it means to be an American, to adhere to the tenets laid out in the Preamble to the Constitution.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice and insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty for ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

These are the bedrock principles on which the country is based, and our elected President has the responsibility to uphold the American ideals and defend the Constitution. Instead, the current president is not considering the general welfare, but rather the agenda of the 30% that voted him into office, placing the rights of the few over the many. Hillary Hanson, in an article for the Huffington Post, shares a video that illustrates the point. “This represents a turning point for the people of this country,” said [ex-KKK leader David] Duke in video uploaded to Twitter by Indianapolis Star photojournalist Mykal McEldowney. “We are determined to take our country back. We are going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump. That’s what we believed in, that’s why we voted for Donald Trump. Because he said he’s going to take our country back. That’s what we gotta do.” Duke further tweeted, “… remember it was White Americans who put you in the presidency, not radical leftists.” No matter how he ended up in the Oval Office, Trump is now tasked with representing all the citizens of the United States, not just the few.

Who will inspire us to let go of the fear of the “other,” the pre-civilized instinct for fight-or-flight? What will it take to eradicate the “us versus them” mentality? What will it take for people to realize that our stories of our own superiority are illusions? What will it take to realize that the civilization’s rise and fall is outside of our control, but that each of us is responsible for acting with dignity and morality?

“’[Our] stories do not end when statues fall,’ Dr. Lucia Allais of Princeton said in an article by Jacey Fortin for the New York Times. ‘We should definitely not think that historical legacies are made, or ended, only by destroying symbols.’”

What is at stake is the planet. Even though it is mainly propaganda, America has always held itself up as a guiding light, a moral choice between right and wrong, between barbarism and civilization, between rules of law and the tyranny of hegemonic rulers. Can we actually step forward and embrace our own best selves and stand by perceived American ideals? Can we embrace a more Christian concept of forgiveness? It may be true more in the promise than in the reality, the aim rather the achievement.

America has behaved horribly: our country has committed genocide against its original occupants, captured and enslaved human beings from other continents, overthrown democracies around the world for our own business interests with disregard of our own professed ideals. We have devolved to autocratic rulers who put greed before anything else. I think the statues are erected by people who romanticized the agrarian society that embraced slavery to enhance its wealth and power. We need to step forward, recognize and acknowledge what we have done, take down the statues, and step into the future.

Great article–lucid, powered by strong personal emotion and wonderful sweep of historical context and comments on revisionism. Good fiction uses imagination to reveal truth; biased accounts of the past that twist facts to twist a point of view are fiction in the service of untruth. The dangerous strategy that if you bang people over the head long enough with distorted views of history they will succumb, accede and believe lies as truth. This essay rises up against revisionist history and establishes real motives behind the erection of these statues and what they represent.

I can’t help remembering that little plaque in Junction City Kansas, in the small park center of town, 1961, dedicated to the first white boy child born in that town. Bars were still segregated there, in Kansas, and the streets in black neighborhood weren’t paved. The situation would likely be the same today had not the Civil Rights movement taken place.

The mix of the personal and sociological in this article is compelling. Thank you, Charles.

Thank you for your comments and good thoughts, Meryl. The most interesting thing about the magazine is generating dialogue.

Thanks for the feedback, Gene. That is a startling story about Junction City, KS. I guess we have to try harder to listen to one another, to see what its like to walk on another’s path.