I am a Muslim. I wrestle with the Quran daily, often replacing rote interpretations with insights more consistent within the context of my life. In 2001 I stood before cameras to disavow the extremists who brought down the World Trade Center in New York City, and more recently hung my head in somber genuflection at Friday prayer services the day after the murder of 50 Muslims at the hands of white supremacists in Christchurch, New Zealand.

And as a Muslim I have a duty at least once in my lifetime to go on Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca as prescribed by the Quran. Mecca, as every Muslim knows, is the most holy city in Islam. It is in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as it has been known since 1932, in historic Arabia. But, as a result of an accumulation of serious concerns about the Saudi regime I have come to a point where I have made a conscientious decision not to undertake Hajj any time soon.

This is a form of personal protest, not against Islam itself, but for Islam by prioritizing its performative dimension over inherited identity. And not by adding to the escalating bloodshed and tyranny crippling Africa and the Near East, but by using a nonviolent protest against a brutal regime that continues to deny its own people, especially women, fundamental human rights; that has committed atrocities against innocent people in the war in neighboring Yemen; and that murdered Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul, Turkey for daring to suggest the Saudi leadership could do better.

And, as a former emergency responder with the New York City Fire Department during the 9/11 attacks on the U.S. that killed more than 3,000 innocent people, I am deeply troubled by the extent to which the Saudi regime was allegedly complicit in those attacks.

Those long-simmering allegations are now contained in a lawsuit filed March 20, 2017 on behalf of thousands of members of the families of 9/11 victims. The action, which names Saudi Arabia as a defendant, was made possible when Congress in early 2016 almost unanimously overrode former President Barack Obama’s veto and amended the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act to allow for lawsuits to be filed against foreign powers allegedly involved in terrorist attacks in the U.S.

Last year, Saudi Arabia filed a motion with the court to block the action, but the judge denied it, and the case continues. It is a complex case that will likely take years to resolve. It has not received a great deal of publicity in the past two years. Suffice it to say here, the affidavit filed on behalf of the plaintiffs offers much detailed food for thought.

From Ritualized Imitation to Radical Introspection

Even before I made my decision to not undertake Hajj any time soon, I found myself steeped in a process of self-questioning and reflection ever since 9/11. Quranic verses that presented Muslims who preceded Prophet Muhammad led me to contrast Islam’s performative nature over identity.

It’s this reciprocal relation between action and reflection that evolved into an epiphany of Islam as radical introspection: a perspective aware of the contingency of its own perspective; an understanding that perpetually prostrates itself before absolute uncertainty; and an ongoing process that seeks daylight from unfathomable ocean depths where we battle our inmost fears.

Hajj then became a metaphor for our inward journey, where the Kaaba that Muslims circle in Mecca signifies the human heart within. That’s really what my story is about.

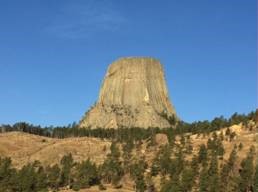

Making Hajj at Bear Lodge

These were but some of the ideas percolating in my head when my son suggested a trip to Wyoming last September. Now it bears mention that I join collective prayers at Friday’s Jumaah, abstain from alcohol and pork, and pause as adhan, the call to prayer, evoke shivers down my spine and goose bumps on my arm. For sure, on Friday I stand shoulder to shoulder and face Mecca with fellow mosque congregants.

But at home conscience dictates I pray facing all directions as a reminder that while Mecca functions as a collective reference point it no longer constitutes my focal point. Rather, my vision undulates in the remembrance that wherever one may turn there is the countenance of Allah.

Keeping this in mind, I took my son up on his offer and we made our own impromptu spiritual pilgrimage last fall to Bear Lodge in Wyoming. It was a joyous, transformative retreat; one that recalled the sweat lodge my son invited me to some years ago in Shinnecock, Long Island. The Park Service sign at the trailhead barely hinted at the aura of timelessness that awaited us.

We saw a handful of hardy souls on the dusty path as we snaked around the soaring monolith that served as a sacred focal point for indigenous people in the area since time immemorial. Little different from the hot rocks in the sweat lodge, we were slow cooked to perfection by the glaring sun beating down on the boulders around us. We connected, laughed as we took selfies, and experienced the natural beauty of Wyoming where the azure blue sky seemed to overflow the horizon in all directions. The morning transported us atop the world looking out on forever.

Conceivably, it may have been this very same path that inspired Lakota Sioux Chief Luther Standing Bear to remark that after all the world’s great religions were written about in fine books with finer covers, each of us must confront the Great Mystery on our own. Looking back, a sense of irony enveloped me in knowing that the science fiction movie classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind was filmed there. One can read about absolute being in scripture; seek it with others in churches, mosques, or synagogues; or experience it on their own terms in wide open spaces: Hajj is also where the heart is…

A Lesson from Hudaybiyyah

Political Islam was preceded by the primordial Islam, our natural disposition (fitrah) to question and discern meaning each moment from embedded and embodied perspectives. However your parents, schools, and census questionnaires label you, from this vantage we are all born in a state of Islam.

And it’s these conflicted notions between political and primordial Islam that have reached a vital crossroad. Will it continue to be usurped by terrorists and despots for self-serving ends? Or will it fulfill its promise by awakening a primal force for social justice and human rights in each and every one of us in a solidarity informed by radical introspection and critical dialogue? It’s up to Muslims to reclaim the truth of Islam, however, and Prophet Muhammad himself shows us how.

Of all of the campaigns of Prophet Muhammad the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah was the most effective in transforming the hearts and minds of people. Virtually unarmed and vulnerable, the Prophet and fellow pilgrims put it all on the line when they set out to make Hajj in year six of his mission. Although they left the outskirts of Mecca without making Hajj that year, Prophet Muhammad entered Mecca triumphant a scant two years later with nary a drawn sword.

Now, I have no doubt that Prophet Muhammad would shun a land steeped in the hypocrisy, moral bankruptcy and the self-idolatry of its rulers – that’s why he fled Mecca in the first place. Indeed, the Prophet’s momentary vision bespoke a multimodal Quran grounded in his univocal firmament. Thus, as the seal of the Prophets, he extended an invitation for each of us to think for ourselves in real time, to apply the criteria of right and wrong step-by-step as he did amidst dynamic times, places, and circumstances.

Building on Khashoggi‘s plea to Saudis, Muslims and the world deserve better. Thus I fervently hope that a bold first step that takes a pacifist stand against tyranny in the birthplace of the Prophet will create a ripple effect. Not only across other faith communities, but in nation states to promote the ethical character of their citizens rather than arbitrary entitlements conferred by borders, race, or the DNA in which they had no say.

What you do is your business however – you will never see the world through my eyes, or I through yours. Perhaps one day we can circle the Kaaba together in solidarity against oppression. But until then, I have my life to live, things to do, family to care for. And to take a line from Jimi Hendrix’s “If 6 was 9”, since I’m ultimately the one who’s going to die when it’s time for me to die, I’ll do the best I can to take my stand, sing my song, and live my life moment by moment immersed in an Islam that makes sense to me.

###

Originally published in the Bookend Review.

Leave a Reply