“[O]ur economic system and our planetary system are now at war. Or, more accurately, our economy is at war with many forms of life on earth, including human life. What the climate needs to avoid collapse is a contraction in humanity’s use of resources; what our economic model demands to avoid collapse is unfettered expansion. Only one of these sets of rules can be changed, and it’s not the laws of nature.” ― Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

There is a painful aspect of global warming (climate change) that is hard to accept: Americans live on a hedonic treadmill (also known as hedonic adaptation) of seeking constant validation that we are living the good life and that it just gets better with making more money and consuming more, driven by novelty-seeking and status competition. Bombarded by constant media conditioning, this perspective is fueled by the socio-economic paradigm we live in, subliminal messaging, capitalistic expansionism, and our “keeping up with the Joneses” mentality renders this version of society desirable, seemingly beyond our choice. “The interconnected environmental catastrophe is the result of a particular lifestyle, a materialistic way of life relentlessly promoted by mass media and governments throughout the industrialized world and beyond. Consuming stuff, most of which is unnecessary, is the key ingredient; excess is championed, sufficiency scoffed at. Far from addressing need, satisfying desire is the driving impulse; the object of desire changes with every new fad, of course, and discontent is thereby ensured, unlimited consumerism maintained,” says Graham Peeples (Nation of Change, “Consuming Stuff: The Polluting World of Fashion.”)

“Since these conveniences by becoming habitual had almost entirely ceased to be enjoyable, and at the same time degenerated into true needs, it became much more cruel to be deprived of them than to possess them was sweet, and men were unhappy to lose them without being happy to possess them.”

– Jean Jacques Rousseau in his Discourse on Inequality (published in 1754)

“This, without a doubt, is neoliberalism’s single most damaging legacy: the realization of its bleak vision has isolated us enough from one another that it became possible to convince us that we are not just incapable of self-preservation but fundamentally not worth saving,” claims Klein. Can these issues be correlated with the rise of global warming effects – on both sides of cause and effect? All these societal problems will be much worse when global warming effects become worse. “It is a civilizational wake-up call. A powerful message—spoken in the language of fires, floods, droughts, and extinctions—telling us that we need an entirely new economic model and a new way of sharing this planet,” says Klein. And the time frame is much shorter than we imagined or would like to believe.

To be sure, addressing the significant kind of behavioral changes on the individual level that can have an impact is a huge challenge. This challenge falls in the realm of personal “psycho-spiritual transformation”; shifting habits and cravings and dependency on the distraction of devices is a monumental transformation. But the good news is that there is already a rising awareness and support for making changes of this magnitude, like the Mindfulness movement and the Green New Deal. From a Buddhist perspective, it is a matter of viewing the world through the lens of compassion, recognizing the interconnectedness of the world. In referencing the philosophy of Stoic Marcus Aurelius, Demian Entrekin notes, “…the right individual behavior is inherently considered within the context of how that individual fits into the community. There is no right behavior without the community.” Judging from historical narrative, a fundamental shift from “me” to “we” is necessary and may be easier than we think. And better for society in the coming decade.

The underlying question is how seriously one takes the threat of global warming. Do we “pay our dues now or pay them later with interest”? It is our kids and their kids who will be paying with interest –- and they are not happy. The Extinction Rebellion and Our Children’s Trust (The Youth Climate lawsuit Juliana v. the United States) demand climate justice. Contrary to what some might say, we do have a choice; we just need to accept the seriousness of the problem and have the intention to make the behavioral and socio-political changes that are necessary.

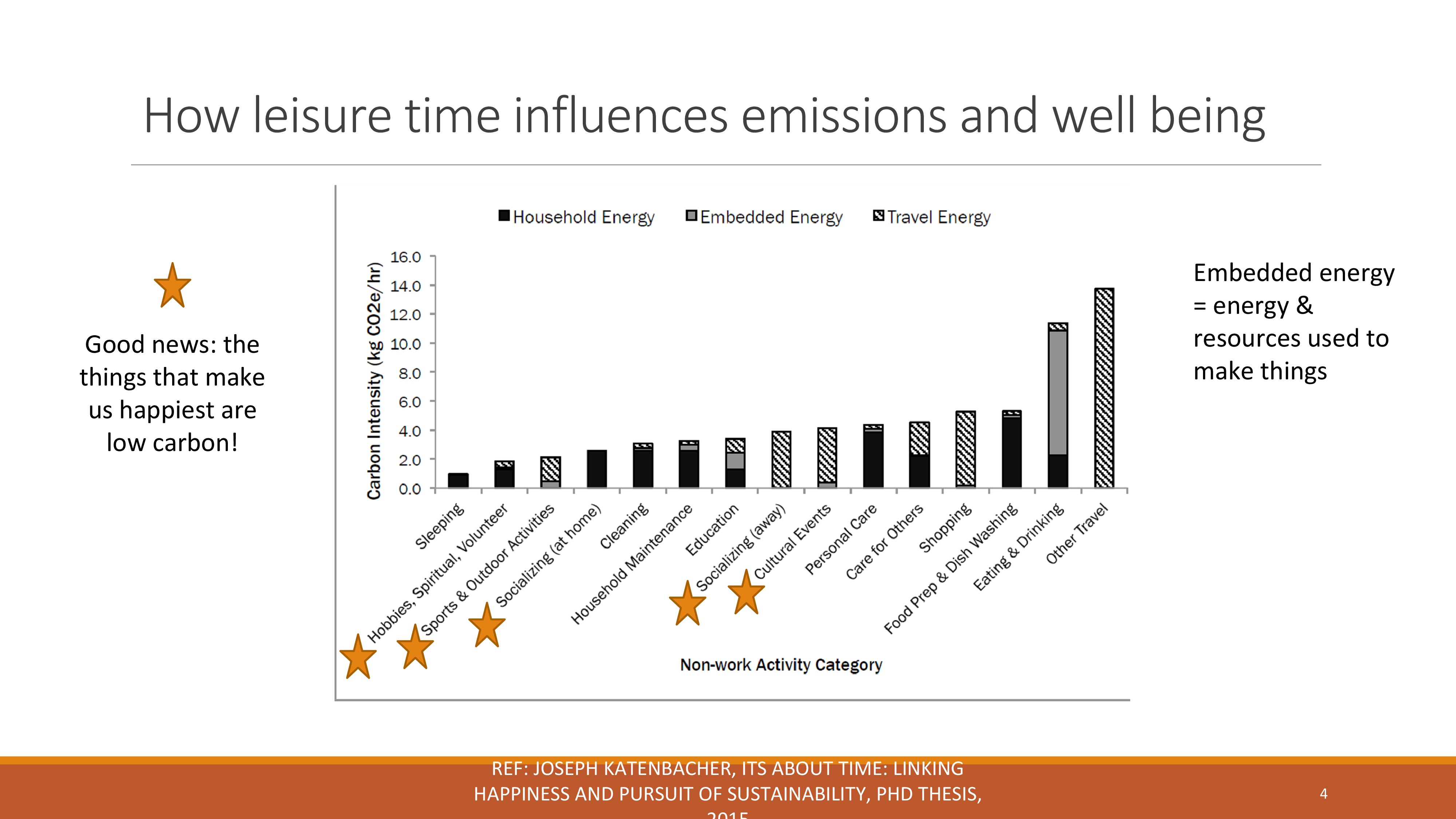

While much depends on regulation of big ag and big business, individuals still have a major role, since personal consumption is a major driver of carbon emissions — everything we buy has a carbon footprint. Certainly, there is a basic level of consumption that is necessary for our survival and another for a reasonable level of comfort. But beyond that it’s a matter of choice — over-consumption or luxury spending has little connection to overall life satisfaction and personal well-being. Not changing behavior is also a choice, and the science is clear that no change in environmental behavior is tantamount to human extinction.

Compounding the problem of conspicuous consumption is the failure of the recycling movement. Virtually everything we buy comes in significant and often unnecessary plastic packaging. All our increasingly disposable goods and copious packaging are all very difficult and expensive to recycle. The problem is exacerbated by the breakdown in communication between the White House and China. “For decades, we were sending the bulk of our recycling to China—tons and tons of it, sent over on ships to be made into goods such as shoes and bags and new plastic products. But last year, the country restricted imports of certain recyclables, including mixed paper—magazines, office paper, junk mail—and most plastics,” claims Alana Semuels (“Is This the End of Recycling?” The Atlantic). Foreign policy and tariffs have driven China to stop buying recycled materials from the United States. Costs of recycling have escalated dramatically, to the point that many cities have stopped collecting or are burning or dumping all material in landfills. Eventually, it ends up in the ocean and then into the world water cycle and food chains.

“As the trash piles up, American cities are scrambling to figure out what to do with everything they had previously sent to China. But few businesses want it domestically, for one very big reason: Despite all those advertising campaigns, Americans are terrible at recycling [placing product categories in correct bins],” says Semuels.

I confess, even those of us who try hard find it frustrating due to the lack of standardization of the plethora of types and varied chemical properties of all the materials, not to mention the fact that, for example, plastic, metal and glass containers must be 99% clean before they are accepted by recycling manufacturers. We mostly, since we are bereft of time affluence, adopt an “out-of-sight-out-of-mind” attitude, eager to move on to the next pressing engagement or titillating experience.

Recycling programs grapple with the “double emission” paradox — we buy way more than we need (for a variety of personal and social reasons) creating “upstream” emissions. “Upstream activities are cradle-to-gate…emission factors, which include all emissions that occur in the life cycle of a material/product up to the point of sale by the producer.” Then we compound the problem through the emissions created by their disposal.

Since worldwide affluence has risen over the past few decades and products and the cost of production have declined due to various factors, this perfect storm of consumerism has fueled a domestic “throw away” culture. Products are more easily obtained—we don’t have to shop at the market when we can order from Amazon in our slippers. Our consumerism is perpetuated by intense marketing campaigns and intentional targeting to addictive behaviors.

Despite not fully contributing in economic upturns or downturns, the average consumer finds themselves compelled to buy things we don’t need, with money we don’t have, to make impressions that won’t last, on people we think will care, to paraphrase a quote widely attributed to author Tim Jackson (Prosperity without Growth, 2017), commenting about about the 2008 recession.

The product development/distribution model is based on the capitalistic notion of infinite growth. “As industrial ecologist Robert Ayres has pointed out: ‘[C]onsumption (leading to investment and technological progress) drives growth, just as growth and technological progress drives consumption.’ Protagonists of growth seldom compute the consequences of this relationship.” The unsustainability of this process is clear.

Tim Jackson also points out that the concept of endless economic growth is unsustainable. International trade has rendered “absolute decoupling” impossible. Absolute decoupling means that energy use and carbon emissions are decoupled from economic growth. In other words, emissions decline as GDP rises; but recent data shows that despite significant advances in energy efficiency, absolute decoupling is not happening. This fact has been proven by tracking the relationship between GDP and carbon emissions in European countries over the past few decades.

Economic growth is antithetical to environmental health. Focus on GDP also creates an externalities problem where there is no cost placed on the carbon content of products. (Economic externalities often occur when a product or service price equilibrium cannot reflect the true costs and benefits of that product or service). As global trade flourishes, it is more difficult to track externalities and thus environmental impact.

“Degrowth economics have a simple solution to global warming: downscale production and consumption and ditch GDP as a measurement of human flourishing. Degrowthers argue that this is possible without affecting our standard of living through measures such as work-sharing, consuming less, and devoting more time to art, family, nature and community. ‘Degrowth means a phase of planned and equitable economic contraction in the richest nations, eventually reaching a steady state that operates within Earth’s biophysical limits.’ — Samuel Alexander (The Conversation)”

“Economists agree that average national output (GDP) is not a good measure of a country’s economic well-being because only what is sold in the marketplace is included in GDP, and all other human activities are ignored,” says Dr. Clair Brown, in an interview about her theory of Buddhist Economics. “Yet GDP is used to measure economic performance around the world. Economists have created several ways to measure pollution and environmental damage, income inequality, happiness, human capabilities, and non-paid activities (both useful and harmful). These metrics have been used to create various holistic measures of economic performance, such as the UN’s Human Development Index, the OECD Better Life Index, the Genuine Progress Indicator, the Happy Planet Index, and Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index. Buddhist Economics relies on these measures, and any one of them is better than using the GDP.

“The major change in perspective for a rich country, like the OECD nations, is to focus on the quality of life of everyone and go beyond consumerism to create happiness and a better world. Our perspective shifts from a focus on chasing after more income to creating a meaningful life and preserving nature. In a Buddhist economy, ‘Practice compassion to be happy,’ replaces ‘More is better,’ and ‘Everyone’s well-being is connected,’ replaces ‘Maximize your own position.’ Our motivation is that we are dissatisfied and want to have a more meaningful life; we want to get off the materialistic treadmill and enjoy the relationships and experiences that make us happy; we want to pass along a healthy planet to future generations.”

“If we are to collectively overcome the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced,” opines Peeples, “environmental considerations need to be at the forefront of our daily lives. A shift in living is required, a movement away from lives based on desire and the pursuit of pleasure to simpler lives based on meeting need, cultivating right relationships with others and the natural world and living harmlessly. The responsibility rests with all of us to live well and to pressurize our governments to act to halt the environmental catastrophe before it’s too late.”

WATCH A SHORT FILM ABOUT THE GREEN NEW DEAL BY THE INTERCEPT AND NAOMI KLEIN HERE (7 MINUTES)

Acknowledgement: I would like to express my gratitude to Charles Entrekin (and his assistants) for the editing and the very powerful additions that help drive these issues home.

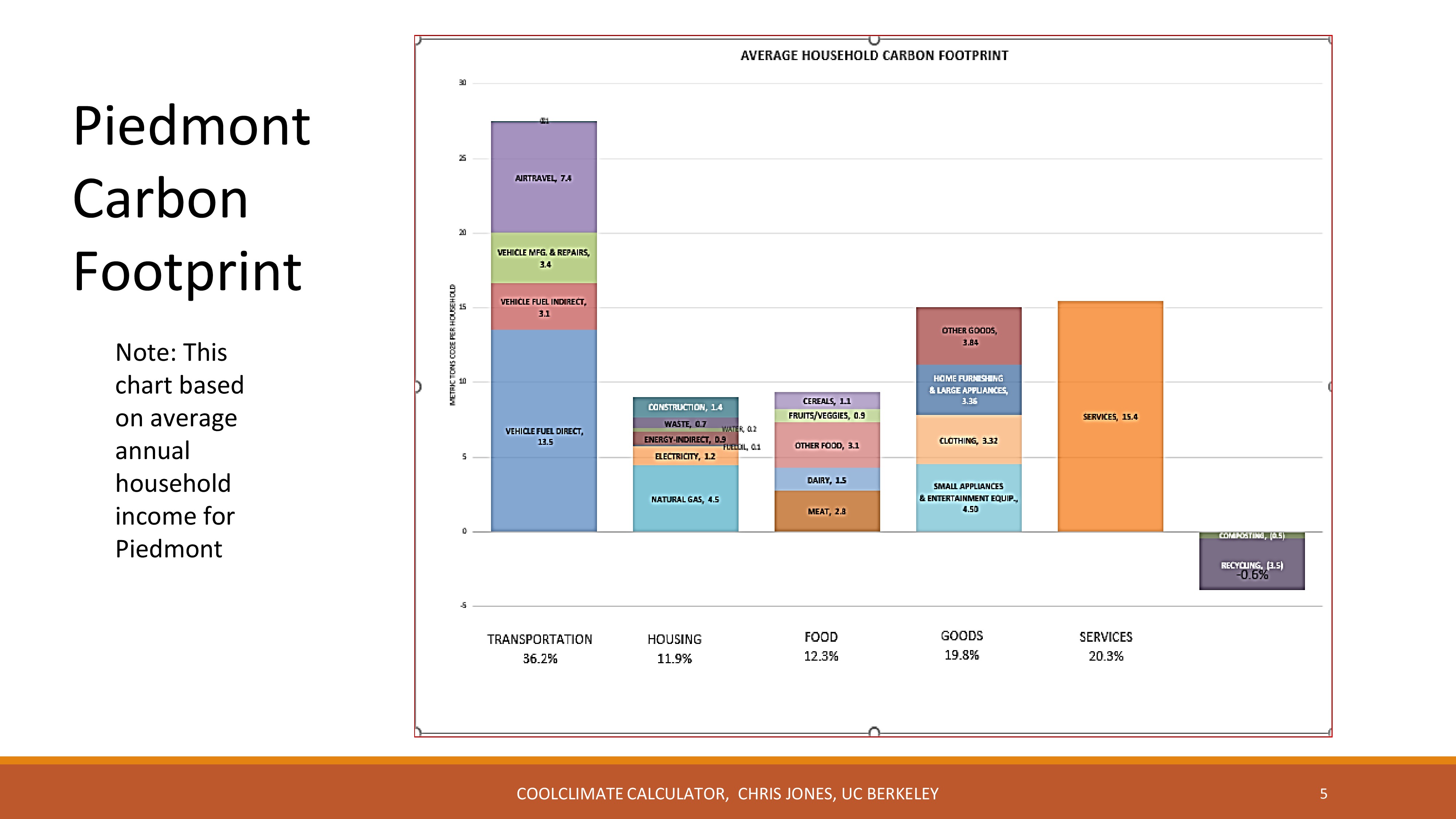

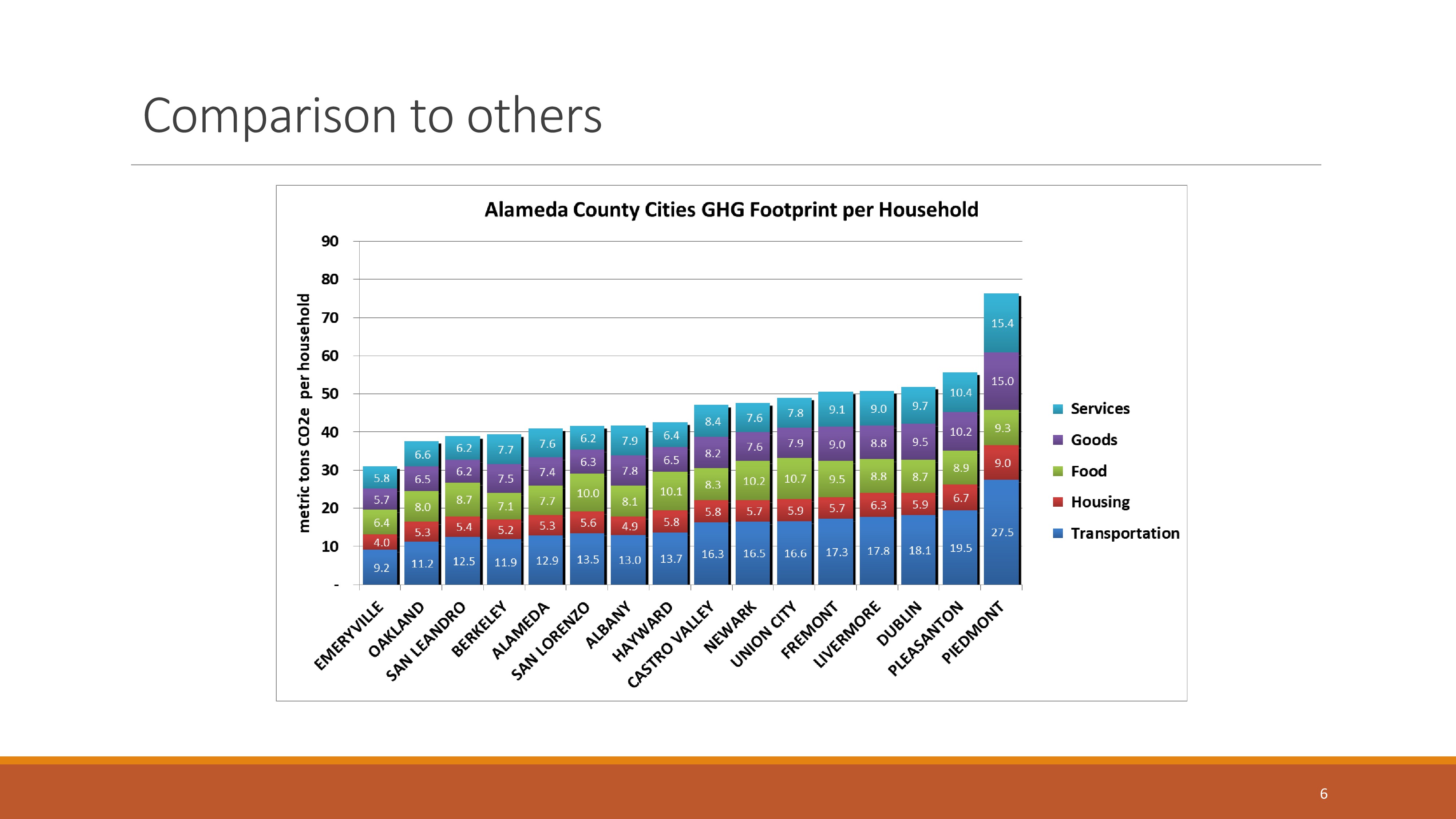

Editor’s Note: While producing this article, author Tom Webster created the following presentation to encourage residents of his community to reduce their carbon footprint. Grassroots organizing begins at home. Carbon Footprint Calculator courtesy UC Berkeley. Nitrogen and Water hyperlinks courtesy The Homeowner’s How-To Permaculture Handbook (Tyler Varian-Gonzalez, 2018).

While I agree (obviously) that we are, by necessity, becoming more “we” oriented, I do worry deeply that the change required is so fundamental that we will only deal with it after the crisis has become undeniable even to the most religious capitalist.

Thanks Demian, point well taken, that is why I call the changes we need to make are at the level of “psycho-spiritual transformation.” A heavy lift for sure but there are rewards on this path such as discovering our true selves and opening our hearts to levels of joy and happiness that have been unattainable in our everyday life experience.