How a time-honored weapon of statecraft has become a debilitating disease.

“We have never been more divided.” That’s the barstool truism that we seem to have embraced, and the evidence of our divisions is not hard to find. At this point it’s banal to point it out. We accept our divided state like we might accept a chronic illness or a battle wound that won’t heal. But we should not accept it.

In a recent article from the National Review (June 1, 2020), highlighted above the banner on the cover, David Mamet writes on contemporary politics through the lens of the plot mechanics of good drama, as if their characteristics were somehow structurally linked. “Why has the Left, intent on destroying the West, put forth no leader, and why has no leader put himself forward to fill the vacuum of power?” I’m not interested here in the questionable logic of his argument but rather in several dramatic claims he makes about the putative Left. The notion that “the Left” is parenthetically “intent on destroying the West” represents a kind of blinking signpost of our factionalized state. Does anyone seriously believe that, say, the Democratic Party is intent on destroying the West? Meanwhile, we have come to accept the idea that there is such a singular thing as “the Left,” that shapeless boogieman otherwise known as Liberals. Curiously, Mamet presumes that only a leader can solve the problem, not a functioning democratic system.

Sentiments like Mamet’s, while seemingly extreme, are in fact common in today’s conservative language, and there are plenty of counter examples coming back at “the Right” from the other side. No one, it seems, is innocent. Mamet goes on to say that “for four years I’ve found the ‘massteria’… around Trump healthy, as energy directed thus was unavailable for the Left’s beatification of a new leader (a fuhrer).” In other words, the good news is that the Left is effectively distracted, or perhaps even internally divided, and lacking a strong man. Mamet seems at ease with the strawman notion that “the Left,” assuming anyone agrees on what that means, would like to beatify a “fuhrer.” This is the bizarre language of faction.

For a counter example from “the Left,” we need look no further than the syndicated columns of a recent issue of the mighty New York Times. “Republicans’ insistence that they have a superior alternative to Obamacare is a zombie lie — a claim that should be dead after having been proved false again and again, but it is still shambling along, eating people’s brains. But why can’t Republicans come up with a better alternative to Obamacare? Are they just incompetent? Possibly,” writes the economics Nobel winner, Paul Krugman (NYT, 6/29/2020). A zombie eating people’s brains? If Krugman intends simply to come across as hyperbolic, he misses the mark and lands instead in the rotting territory of the absurd. We could perhaps dismiss these two figures, Mr. Mamet and Mr. Krugman, as edge cases of partisanship and then chock it up to the extremes of the spectrum of Left versus Right, the drama that sells journalism. But just about any further reading in the press reveals a pervasive penchant for faction. Over and over again, radical examples like these get past these stalwart editorial boards.

This doesn’t even begin to address what passes for television news at this point, where unapologetic divisiveness has become the guiding rule rather than the exception. We can choose to call this opinion journalism or even entertainment, but it all adds up to the same thing. Factionalism is churning at peak performance like a well-oiled machine on a mission. There is plenty of research to back this up. “Pew Research Center conducted its foundational ‘Political Polarization & Media Habits’ report. That study – which was conducted among web-using adults only – revealed that political polarization had bled into Americans’ news preferences. The new 2019 data suggests that the chasm has widened in the five years since.” In a five-year span, the gap in trust between “the Left” and “the Right” has grown by as much as 25%. That’s an arresting number. 25% in five years? What is going on here? Why are we growing more and more divided, and at an accelerating pace?

When we search for foundational reasons that explain the factious state of our political environment, we might consider Federalist 10 where Madison drolly states that “as long as the reason of man continues [to be] fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed.” We can almost see Madison winking at us here because, of course, the “reason of man” will remain fallible forever, and therefore factions will naturally develop in a system predicated on freedom. Liberty + Reason = Faction. Case closed. But his concern is not happenstance. He wrestles with the serious challenge of a democratic system’s ability to hold itself together. We have no guarantee, in other words, that our democracy, or any democracy, will continue to flourish or even function. Democracies have flowered in the past and then withered, and factionalism is usually at the heart of the failure. “Among the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of factions.” If we take Madison at his word, he warns that functioning democratic governments demand that we pay close attention to the systems that can “break and control the violence of factions.” To break and control — these are serious considerations of structure and governance.

I’d like to take a step back for a moment and explain that I recently began considering the topic of divisive factions after an exchange with some of my family members. Like many families, our extended brood is made up of a disbursed mixture of conservatives and liberals, and our ability to communicate has grown harder and harder in recent years as a direct result of increasingly divided political sentiments. The family fabric itself has grown destabilized, stretched thin and torn by divisive ideas that elude our ability to fully grasp. Statements like Mamet’s and Krugman’s are not only reserved for incendiary essays in the media. We have become energetically factionalized in everyday life. In the conversation I had with my family, I took the seemingly moderate position that we are in fact more alike than different and that our current state of divisiveness has grown exaggerated, based largely on the fabrication of differences. Our differences, in other words, appear to be overstimulated.

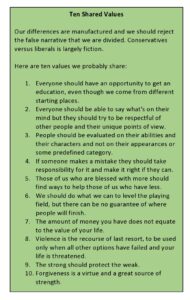

But perhaps it’s not such a moderate position after all. To suggest that we have more in common than not might represent a radical proposition in 2020. To make it more concrete, I proposed ten values that “both sides” shared. I could have easily provided many more than ten shared values, but it seemed like an appropriate number and a reasonable place to start. The conversation continued on for several days, and as I thought about it more, it occurred to me, almost in passing, that we had somehow managed to aim the statecraft weapon of “divide and conquer” on ourselves. That thought got me to digging.

The phrase divide and conquer puts a name to an ancient military and political technique. The linguistic root of it stems from the term divide and rule, or divide et imperia. You can rest assured that you are dealing with a dog-eared concept when there’s a Latin term for it. The distinction between 1. conquer and 2. rule is, of course, quite important. It is one thing to conquer a nation or a people and quite another thing to rule it. As it turns out Divide and Rule has techniques that can be used for both.

Returning to Federalist 10 for a moment, Madison employs the metaphor of a “mortal disease” as a way to explain the dangers of a factionalized democracy. He also defines “faction” as a “vice” that requires a “proper cure for it.”

The instability, injustice, and confusion introduced into the public councils have, in truth, been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have everywhere perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations. (Federalist 10)

Divisiveness and discord represent the leading causes of death for democracies, and they will be employed by the “adversaries of liberty” as long as they continue to be fruitful. Who, we might ask, are these adversaries? As we will see later in this paper, democracy has many adversaries, and those adversaries are actively working to weaken western democratic governments.

Good leadership, moreover, by no means provides a guarantee in a democratic system. “It is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm.” What matters most, in other words, is the democratic system itself. According to Madison, the republican form of democracy provides the remedy for these ills. A republic, unlike a purely popular democracy, places special burdens on a set of selected individuals who bear the shared responsibility of stewardship for the common good of the government and all of the people that it represents. “A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking.” In a republic, as Madison’s argument goes, the elected representatives function as “a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice to temporary or partial considerations.” According to Madison, larger republics are better equipped than small ones. In larger republics a greater number of fit representatives can pursue the greater good which creates greater stability. This strength-in-numbers position provides structural form to Madison’s systemic argument, a system, as we like to say, of checks and balances. Perhaps he is right, but then again perhaps Madison is merely speculating, or even extrapolating. The size of our current republic dwarfs the size of Madison’s, and we remain susceptible to raging factions.

While Madison sees factions as a sickness that requires the cure of a properly designed republican form of democracy, factions can also be created and exploited as tools of warfare in the pursuit of aggressive statecraft. This learned practice is less about the nature of humans who tend to disagree, and more about the human ability to wage war. The approach can be traced to ancient Roman strategies, and it also appears clearly in the Art of War by Sun Tzu. Stated simply, in warlike situations, the natural tendency of humans to factionalize can be orchestrated in order to defeat adversaries. Machiavelli covers this martial technique in his own Art of War, and he frames it in a variety of different contexts.

For Machiavelli, dividing the adversary’s forces is a critical technique to both defeat and to rule. With respect to defeating an adversary, “a Captain ought, among all the other actions of his, endeavor with every art to divide the forces of the enemy, either by making him suspicious of his men in whom he trusted, or by giving him cause that he has to separate his forces, and, because of this, become weaker.” This form of tactical divisiveness plays out in two dimensions. In the first dimension, the enemy captain suffers the loss of fidelity and loyalty of his men. His ability to command with confidence damaged, the enemy captain’s power is diminished. We will return to this line of thought later in this paper. In the second dimension, the enemy captain will break his ranks up into smaller ranks so as to avoid the potential that they might unite against him. This is a simple mathematical advantage problem. In both cases, the captain is “made weaker” through the factions created within his ranks.

Machiavelli avails himself of classical examples in history to illustrate his point further and perhaps to demonstrate his acumen. Dividing people against each other is not merely a time-tested method. It is also the lesson of a classical education. Those who study the histories of Greece and Rome acquire the language and technique of classical faction-making.

You know how Hannibal, having burned all the fields around Rome, caused only those of Fabius Maximus to remain safe. You know how Coriolanus, when he came with the army to Rome, saved the possessions of the Nobles, and burned and sacked those of the Plebs. When Metellus led the army against Jugurtha, all the ambassadors, sent to him by Jugurtha, were requested by him to give up Jugurtha as a prisoner; afterwards, writing letters to these same people on the same subject, wrote in such a way that in a little while Jugurtha became suspicious of all his counsellors, and in different ways, dismissed them. Hannibal, having taken refuge with Antiochus, the Roman ambassadors frequented him so much at home, that Antiochus becoming suspicious of him, did not afterwards have any faith in his counsels. (Art of War, Book Six)

This tidy list of historical examples outlines a diverse array of techniques for dividing people, especially powerful people, against themselves and each other. We have here the destruction of property and food sources for some but not others, the preservation of possessions for some but not others, the arrest of a carefully selected individual followed by a letter campaign to sow seeds of doubt in his comrades, the excessive and public display of friendship but only to a selected individual. In order to become schooled in the Art of War, and therefore in the art of aggressive statecraft, one must become deft in the art of creating factions.

So we can see a clear distinction between Madison’s formulation of disease/cure and Machiavelli’s formulation of conquer/rule. We must now traverse the chaotic space between these two models. While Madison wrestles with the nature of democratic systems and the fallible “reason of man,” Machiavelli reveals a toolbox for the martial captain who manipulates armies and peoples in order to achieve victory. Fast forwarding to our contemporary situation, the RAND corporation issued an exhaustive outlook in 2008 called “Unfolding the Future of the Long War, Motivations, Prospects, and Implications for the U.S. Army.” This book-length report lays out several forward-looking prospects for the ongoing struggle between the Islamic world and the West. In their own words, “the long war has been described by some as an epic struggle against adversaries bent on forming a unified Islamic world to supplant Western dominance, while others describe it more narrowly as an extension of the war on terror.” The scope of RAND’s “The Long War” is both exhaustive and inconclusive. The paper offers a blunt discussion on the options for “Divide and Rule” and we can draw a straight line between Machiavelli and RAND.

“The Long War” defines Divide and Rule as one of ready-made tools that can be deployed by the US Military from the aggressive statecraft toolbox. While there is no mention of the historical context of Divide and Rule, the RAND authors wield the technique much the way a mechanic might wield a socket wrench. It offers the simple, dry language of military bureaucracy:

Divide and Rule is a strategy that focuses on exploiting fault lines between the various SJ groups [Salafi-Jihadism/Salafi-Jihadist] to turn them against each other and dissipate their energy on internal conflicts. For example, the United States could conceivably exploit the tensions that exist between local SJ groups that wish to concentrate on overthrowing their national government and al-Qaeda, which aims to fight a transnational jihad. In such a strategy as Divide and Rule, the inevitable choosing of sides may inadvertently empower future adversaries in the pursuit of immediate gains.

The authors openly concede at least one risk of Divide and Rule in that it “may inadvertently empower future adversaries in the pursuit of immediate gains.” The risk highlighted here by RAND is cited only as an essential risk to the US Army and perhaps the Western powers more broadly. But these divide-and-conquer techniques, by design, wreak havoc on the culture. There are certainly other risks that should merit at least some form of acknowledgement, such as the physical and emotional risk to the children, the poor, the uneducated and the disabled. In fact, we might acknowledge those risks here at home as we confront our own currently divided culture. How many problems are we unable to solve as we squabble amongst ourselves? The bloodless term “collateral damage” comes to mind for such unstipulated risks.

But we are talking about a weapon here, and the RAND authors delve more deeply into the tactics of a Divide and Rule strategy. They provide practical entry points for practitioners who want to engage the adversary with the techniques. Practitioners will need to educate themselves on the fault lines where factions can be exploited and tensions can be fueled to create divisions:

If we place Divide and Rule in the context of the project’s broader GTI [Governance, Terrorism, and Ideology (Construct)] framework, we find that this strategy is dominated by the ideological component because it focuses on fault lines and contradictions in SJ ideology to turn the various jihadist groups against one another. In order to execute this strategy, U.S. policymakers and intelligence analysts would need to develop a keen understanding of the nuances of SJ ideology as well as its historical evolution.

It’s a bit like reading a cookbook, and this language sounds eerily familiar to our own situation in the West. The Divide and Rule technique requires ingredients like “fault lines and contradictions” that can be exploited and expanded. These fault lines will require policymakers to educate themselves on the “nuances” of the adversary’s history and ideology. Clearly, these weapons are unlike kinetic munitions (guns and bombs) that require soldiers to go bodily into the field to fire upon the bodies of the enemy. The nuanced weaponry of Divide and Rule is employed by “policymakers and intelligence analysts” who are schooled in psychological techniques. We should harken back to Madison’s idea that factions are a disease of human societies, because the RAND authors clearly state that the fault lines and contradictions are already there as a natural aspect of the society. Ergo, the proficient practitioner of Divide and Rule locates those pre-existing fault lines, studies their characteristics, and exacerbates them to the point where they turn the “groups against one another.” Looking at this RAND strategy feels all too much like looking in the mirror.

I’ve talked briefly about the polarized press, the natural tendency toward factions in democratic governments, and the adversarial instigation of factions in times of war. But there is a relatively new ingredient in the odious brew of our factious state. Social media, broadly speaking, has furnished the world with a platform where anyone and everyone can insert their unmediated messages into the public discourse, and they can do it with a few keystrokes from anywhere. Social media platforms, it must be said, make their money through advertising on those platforms, and more viewers means more revenue. More conflict means more viewers. It offers social media platforms a simple formula. In a December 2019 article in The Atlantic, the authors quote Madison’s Federalist 10 as an opening into the examination of social media and democracy: “social media turns many of our most politically engaged citizens into Madison’s nightmare: arsonists who compete to create the most inflammatory posts and images, which they can distribute across the country in an instant while their public sociometer displays how far their creations have traveled.” It would seem that Madison’s 1787 examination of faction is now quite current, and social media is the next chapter in divisive public discourse.

One also senses that the financial pressures on the press and the audience-jacking by social media have driven the press to act more and more like social media. In other words, it appears that the lines between journalism and social media are beginning to blur. Is Twitter news or is it social media? When prominent officials use Twitter to communicate policy, we must answer “both.” From a business point of view, it’s a messy situation in the digital media landscape, and digital media means the news. It provides, furthermore, the information that drives our ability to know, to think, to discern, to render judgement. This is especially true since citizens cannot be present for the action — they must rely on their representatives and the press. Without a functioning press, we are driving blindfolded. In an Esquire article from December 2013, Luke O’Neil confesses that “in order to make a living, those of us who had the bad sense to shackle ourselves to a career in media before that world ended have to churn out more content faster than ever to make up for the drastically reduced pay scale.” So much has been said and written about the dark vortex of the Internet that I will refrain from recapitulating that story here. But it has become an over-sized factor in the modern understanding of faction. We appear to have taken the ordinance of faction, digitized it, and pointed it back at ourselves. Here’s O’Neil again: “this conflation of newsiness with news, share-worthiness with importance, has wreaked havoc on the media’s skepticism immune systems. It didn’t happen out of nowhere; it’s a process that’s been midwifed by the willful blurring of the lines between fact and fiction on the part of a key group of influential sites, that have, unfortunately, established a viable financial model amid the wreckage of traditional media.” O’Neil points out that this does not impact only fringe media sources. It impacts the most renowned media players as well. Is this a disease or a weapon? The answer, it seems, is not so easy to answer.

The year 2020 may represent a new extreme in the divisive fever infecting Western culture. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of social unrest and race-based protests and counter-protests, not to mention rioting in the streets throughout the western world, we have discovered new, and renewed old, ways to inflame factions. The figure of Madison himself, a slaveholder of over 100 people and one of the architects of the 3/5th compromise, must now be considered as a divisive figure. There’s simply no getting around that hard fact. Furthermore, in the midst of the global pandemic, we consider it a political statement to wear a face mask. We have not put Science in the back seat. We tossed it out of the vehicle and replaced it with Faction and gave it the keys to the car. As O’Neil points out, we are all “blurring the lines between fact and fiction.”

We gaze confoundedly at our factious state, and we see that the competing notions of disease/cure versus conquer/rule fail to describe our condition. We are lost and scrambling in the space between the two. With so many participants engaged in the mechanics of division, it becomes impossible to find a single source or actor that we can blame. We might think instead of a forest fire burning out of control. The wind picks up to fan the flames and the flames move to spread the fire. We can’t simply blame the information warfare of Vladimir Putin or social media or the Left or the Right. The hot spots are all around us. Problem-solvers are fond of straightforward cause-and-effect relationships because they lead us in a clear direction that provides the feeling that we can solve the problem. But what happens when there are so many causes and so many effects that there is no clear source of the problem? What happens when the fire is burning out of control?

There is still another angle we must consider here, and this angle takes us right back to Mr. Machiavelli, RAND and the ever-handy toolbox of Divide and Rule as a weapon. What if we consider the proposition that we are at war right now, and divisiveness is the weapon of choice? What if the West is in fact under attack? What if anti-democratic forces are actively orchestrating discord in various domains of public discourse? What if these agents are actively undermining our systems of governance as a means to erode the potency of democracy in the world? What if our adversaries are using tools that we built and handed to them? What if we are actively and unwittingly supporting the attack on democracy? We cannot, and should not, dismiss these questions. The evidence of an ongoing and sustained attack is all around us. Franklin Foer of The Atlantic writes that “a year after the [2016] election, the Department of Homeland Security told 21 [US] states that Russia had attempted to hack their electoral systems. Two years later, a Senate report publicly disclosed that Russia had, in fact, targeted all 50 states” (June 2020). And as a result of these hacks, Foer further points out that voting rights are now back in the fray for partisan behaviors. “The subject of voting divides Republicans and Democrats. Especially since the Bush v. Gore decision in 2000, the parties have stitched voting into their master narratives. Democrats accuse Republicans of suppressing the vote; Republicans accuse Democrats of flooding the polls with corpses and other cheating schemes.” Voting rights have always been a partisan topic, and they occupy the very heart and soul of a democratic system. Erode faith in voting and you erode faith in democracy. Recall that it was Madison who proposed the ratio of the Three Fifths Compromise, which perversely calculates how many representatives a state can have based on how many citizens they have.

But the digital battleground extends beyond direct assaults on election systems. The ongoing attack includes nearly all forms of democratic media. David Von Drehle calls out the divisive tactics of Putin’s Russia: “not sure what to believe? Bingo. This fever of mistrust is the desired symptom of a powerful virus — a confidence-sapping worm of mutual suspicion — that Russia has planted in the operating system of American democracy. At little cost and with surprising ease, Vladimir Putin and his government have exploited partisanship and social media to serve Russia’s long-term goal of weakening the West by encouraging disorder and disunity.” One of the outcomes of successful Divide and Rule techniques is to erode trust systematically. Machiavelli and RAND spelled this out in their didactic prose. When people distrust each other, how do they unite around a common cause? When the people distrust the press, how do they make informed decisions about what is true? When social media succeeds because we are divided against each other, how do we respond? When the press is under siege economically and politically, how do journalists stand their ground? Seen from this vantage point, there may not be a meaningful distinction between a disease and a weapon. This “virus” is now the new disease, at least in the modern sense of a virus specifically designed to undermine digital technologies that are the backbone of the communication infrastructure, the broken language of the democratic discourse.

This weakening is not purely a domestic problem internal to the democracies of the West. It is not just about friends and families unable to communicate and collaborate. It impacts the ability of democratic governments to engage with the rest of the world, and that is the ultimate point of it. Drehle goes on to argue that “millions of us are unsure whether elections will be free and fair, whether the news we consume is real or fake, whether our foreign policy serves national or personal interests. This is a massive victory for America’s enemies. A climate of mutual suspicion at home erodes our ability to affect events abroad.” The truth that anti-democratic foreign powers are actively sowing divisions in the West is not even a credibly debated topic at this point. Robert Mueller pointed out unequivocally in public hearings that we are under attack every single day. It is widely considered to be an empirical fact that Putin, among others, regularly and actively engages in divide-and-conquer techniques to undermine Western democracies by destroying the credibility of the press and pitting factions against one another.

It does not appear to be the Russian government, per se, that has become the enemy of democracy, the sower of division and faction. Vladimir Putin, rather, now stands at the front of a larger group of extremely wealthy and powerful individuals who have managed to rise above the untidy and bureaucratic workings of government, and who have achieved the status of Hegemonic Freedom. He can be viewed more like the frontman of a syndicate who happens to have a day-job as “elected” president of Russia. “Putin has transformed the anarchic plunder of the 1990s into a centralized structure of state-approved oligarchs, with himself at the top of the pyramid.” The trail of evidence for these claims has been documented over and over again, but when the press has had its credibility trashed by the corrupt system it tries to document and uncover, how can we rely on the claims of those critical pieces of journalism? Where is our grounding in fact and in evidence? And as for the man, Drehle points out that his wealth speaks for itself since “Putin is believed to be among the richest people on Earth — impressive for a man who has worked his whole life for the government.”

The West is not innocent in such divisive orchestrations, manipulations and foreign interference. There is plenty of blame to go around here at home, and the Divide and Rule toolbox has been used extensively by the Western colonial powers, and it remains an active technique as plainly evidenced by the discussion of this in the RAND paper. It appears, once again, that no one is innocent. This line of thought articulated by Drehle about Putin’s Russia could easily be added directly to the RAND cookbook as a case study for Divide and Rule techniques: Putin “supports whichever [Western] candidates are most divisive and amplifies whatever arguments are most bitter. Whoever is freaking out on Facebook or Twitter is a potential ally in his cause. At the State of the Union address, he no doubt enjoyed both the snubbed handshake and the ripped speech.” We do it. They do it. We all do it. But at what price?

The divisions in the West are too deep to explain with a single cause. They are rooted in our natures and they are reinforced by our history, our philosophy, and our actions. We have our own tribal divisions, and our enemies exploit them daily. Now what? Even if we are under attack today by anti-democratic forces, and all evidence points in the affirmative, we must look inward if we want to know the thing for what it is.

The critical question at hand is the question of contemporary democracy and its ability to survive. I have said it already, and I’ll say it again: No one, it seems, is innocent. But our own culpability does not absolve us of the imperative to point a way forward. We must not sit back with our arms crossed and make high-minded moral pronouncements. We must take action on our own behalf. Looking back at what instigated this investigation, which was the idea that our differences are largely fabricated, I am led to the idea that we as individuals must assert our own sovereignty as agents in this divided state. We cannot sit back and bemoan our factions and wallow in the slop with the dividers. We must not assume that we are powerless to change the way things are now. That is the very definition of a failed democracy.

Fifty years after Madison’s Federalist 10, Tocqueville states unequivocally in Democracy in America that “when one wants to speak of the political laws of the United States, it is always with the dogma of the sovereignty of the people that one must begin” (Chapter 4). The sovereignty of the people means quite simply that individuals possess both the power and the responsibility to take matters into their own hands. They do not wait for the larger forces of government or nobility to direct their options, their choices, or their actions. In a rhetorical flourish, Toqueville declaims that “the people reign over the American political world as God does over the universe. They are the cause and the end of all things; everything comes out of them and everything is absorbed into them.”

The claim that I stated in the opening sentence that “we have never been more divided” is not a fact, but rather it is a choice. Let us not be mistaken: this species of choice is what makes democracies work, and it is furthermore what makes them resistant to the diseases that come from within and the assaults that come from without. “The collective force of the people will always be more powerful to produce social well-being than the authority of the government” (Toqueville, Chapter 5). And it is this vital force that strengthens democracies against their adversaries, both internal and external. Social well-being is inextricably tied to the ability to defend a democracy against anti-democratic forces. Nations that have forsaken the sovereignty of the people are already in trouble. As Toqueville plainly warns, “I say that such nations have been prepared for conquest” (Toqueville, Chapter 6). There must come a time for each of us when we step back and see our divided condition as something that we control and not as something that controls us. In that moment, we would question the very nature of faction, and we would take ownership of our assumptions and our choices. Perhaps, in fact, that time has arrived.

References

Federalist 10, Madison

The Federalist (Dawson)/10

Art of War, Machiavelli

The Art of War (Machiavelli)

The Long War, RAND

Unfolding the Future of the Long War: Implications for the U.S. Military

Democracy in America, Toqueville

Democracy in America

National Review, Mamet

The Code and the Key

PEW research

In recent years, partisan media divides have grown, largely driven by Republican distrust

Atlantic, Jonathan Haidt and Tobias Rose-Stockwell

Social Media Is Warping Democracy

Esquire, Luke O’Neil

The Year We Broke the Internet

Washington Post, David Von Drehle

Has Putin already disrupted the 2020 elections?

Washington Post, Adam Taylor

How rich is Vladimir Putin? Official wealth and income disclosed ahead of Russian election – The

New York Times, Trump’s Love for Putin: a Presidential Role Model, Stephen Lee Myers

Trump’s Love for Putin: a Presidential Role Model

Atlantic, Putin Is Well on His Way to Stealing the Next Election, Foer

Putin’s Goal Is to Bring Down American Democracy

NYT, Kevin Roose

What if Facebook Is the Real ‘Silent Majority’?

Washington Post, Elizabeth Dwoskin and Craig Timberg

Facebook removes Russian disinformation network …

Politico, Alan Abramovitz and Steven Webster

‘Negative Partisanship’ Explains Everything

Reading this exhortation toward common sense and a middle way requires rare mental stamina but it’s worth it. I admit I had to pull over a few times, and this is one of them, before returning to it. I looked at an early cover picture on one of Dolly Parton’s cd’s for a respite. So far, the reliable salability of divisive extreme perspectives stands out, to say nothing of its addictive tendency. But I have faith in writer’s urgent motive for wholeness. History certainly has shown such fractional behavior we’re struggling with leads to perilous paralysis. We’re not sow bugs who can curl up and roll away from a german shepherd’s curious but enormous nose. To be cont’d. . . .

This essay rises out of a broken heart held together by a mind determined not to forget how the heart sings in all of us