Hammond, Louisiana, 1964

On the afternoon of my first jump, wind gusts rocked the Cessna 170 on the ground and swept bright clouds across the sky. Four weekends in a row had brought violent winds up from Texas and the Gulf, and all our skydiving flights had been cancelled. There was much discussion between the two pilots, one to fly and the other, the jumpmaster, to locate the jump spot and put me out of the plane. They decided to take a chance.

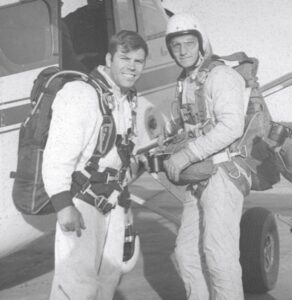

Without commercial licenses they weren’t allowed to get paid, but they did it for the free jumps. In ’64 sport parachuting was an extreme sport with few regulations. Our main chutes had been used on jet fighters; they were heavy and offered zero maneuverability, so the guys cut out panels of the parachute’s fabric and attached toggle lines. By pulling down on one side the skydiver could pinch a panel shut; air rushing into the other side would turn the chute. One guy kept cutting more panels to give himself greater forward speed and ability to turn, until he broke both ankles.

“It steered great!” he said.

Some of our pilots had been in Vietnam when it was Indochina, and in the secret war in Laos. Another of them had a contract from General Curtis LeMay—Dr. Strangelove—to train special ops soldiers in martial arts. I didn’t know his name at the time, but 38 years later Lloyd Kelly turned up in my first Spalding University Creative Writing workshop, and now he’s one of my best friends.

Another pilot who ferried jumpers specializing in high-altitude jumps would soon captain a DC-3 for Pablo Escobar— drugs.

He gave up Escobar when the feds caught him, and soon after that he was shot dead in Baton Rouge.

These hard asses would only speak to me, a mere Tulane student, when necessary, but they were suitably impressed when my girl—a lookalike for the movie star Lee Remick—stepped up beside the plane. She kissed me, and I winked at her and climbed aboard wearing the two parachutes. Then we taxied along and lifted off into the cross wind.

We circled and banked and rose; green and brown squares of farmland shrank until they were far away; trees and cows and cars grew small, and finally at 3,000 feet, the roads shriveled to pencil lines.

Over the jump spot the engine cut back a little and we slowed, the spotter yelled into my ear “Go!” and I climbed out.

I placed my left foot on the small step below the door, and my right foot on the tire. My hands grasped a strut supporting the wing. The engine noise amplified near my head and the wind flapped my cheeks. The jumpmaster was supposed to reach out and slap my calf, the signal to jump.

I’d fold my knees and let my boots rise into the air. During that moment I’d be attached to the plane by fingers and thumbs only. If I released hands and feet at the same time, the horizontal stabilizer would slice me in half or decapitate me. It was a matter of folding my knees, feeling my boots rise, then shoving off from the strut neither too quickly nor too late. The push would send me downward on a diagonal line The stabilizer would miss my head.

Thus far I was fine. I’d prepared so carefully for this moment that it seemed I was moving in slow motion, seeing forward into time. But now something was wrong with my calf. It seemed to have its own consciousness and a tremor as it anticipated the slap. Mr. Calf Muscle was ready to go, poised for the knee to bend and the foot below to float skyward. Captain Calf knew its job, to take that slap and send a quick pain flashing along the nerves into my brain.

But there was no slap, unless I hadn’t felt it. I should have felt it by now, and my calf knew that. Sensitive Master Calf had felt the phantom slap, the shadow twin of contact dreamt and imagined and rehearsed. My leg had found the nothing-there, the inverse chord; this not-slap provoked and aggravated Mr. Expectant Calf.

Whether it had detected an absence or a presence I could worry about later—later? It knew more than I did, but I wanted to argue. Surely my leg wouldn’t betray. Perhaps I’d gone into shock.

But wait, I was experiencing this in slow motion, so perhaps the spotter’s hand was moving through air in slow motion right now, fluttering against the wind, approaching my body with the speed of cool downhill molasses. That must be it. This was a waking dream, a daydream but a good one, exactly like what my friend Dennis Pearson had described about exiting a C-46 with his smoke jumping buddies over the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana. This had to be the same slow motion he’d conjured up late at night before the fire in our cabin. I wasn’t scared because from all his stories I knew how it felt, how it was supposed to feel. And I heard his voice in my head, low and calm. Mr. Competence, he was. He said, “That’s right Luke. You got the tire. You got the step. Hold tight on that strut. That’s it. Wait for the slap. Doin’ fine.”

Then a high-pitched angry bark sliced through the engine noise and I turned my head as the spotter screamed a second time,.

“Get back in the plane!”

Something was wrong, I thought. It’s all been in slowed-down time from the first step outside, so telling myself that the hand was late made no sense. Unless there were two alternate dream times at work here, my leg in slow zone one, his hand in slower zone two.

The spotter was angry. I was all of a sudden sick. Get back in the little 170? How? My steps to out here in the roaring blue—so well rehearsed, but how to repeat them in reverse? My left calf, so sporty and philosophical a moment ago, fell silent.

I back-crawled inside with a weak stomach and a headache and indignation.

“What happened?”

“You took too long getting out there and we passed the spot.”

“Oh.”

“We’re making one more pass and that’s it.”

I nodded.

The plane banked and roared as it lurched, swept in a big fast climbing circle while I attempted a dry swallow. Gone was the comfortable storehouse of memories of all my previous jumps, I mean of all Dennis’s jumps, my borrowed memories. Gone was the thrill of having my girl watching, from so far below on hard planet Earth. Planet of rock and stones, I realized now. How could I climb out again, shaky and weak? I was scared. I’d felt proud of my slow motion sense of calm, but it must have been actual slow motion as well.

How fast was I supposed to move? This now seemed the central question and it had never once come up in training, nor in the stories of Dennis.

The airplane leveled and slowed. The jumpmaster said, “Get out.”

This time I went like a squirrel, clutched the strut tight, and planted my boots. He slapped my leg. It came as a sting, nothing like that metaphysical shadow my calf had been reporting earlier; I bent my knees and let the boots rise. I extended my legs, shoved off with my arms, and traveled down on a diagonal line as the stabilizer missed my noggin. I forgot to count the seconds, “one thousand, two thousand…”

The static line should snap open my chute at three to four seconds. If more than five passed, something would be wrong. Even though I’d forgotten to internally speak the numbers of the seconds, my body was counting; when Second Five arrived I knew it.

On “six” I was to look up and check whether the main chute was twisted above me. If it was I’d curl into the fetal position, which would flip me to my back. I’d hold the reserve chute tightly to my chest with my left arm, and yank the rip chord with my right hand. As the chute opened I’d gather the shroud lines—shroud lines—in both hands for an instant, then throw the loosening parachute forward, out in front, so the reserve would have a chance to inflate and clear the tangled main streaming from my backpack. If the two chutes twisted together I’d be a human streamer all the way into the ground.

That was one type of malfunction, but there were others and I was supposed to remember different responses to each.

With this new crisis, falling through the sky, slow motion calmness returned, and sickness evaporated. I had ages in which to observe the Fifth Second fading into past time, and the Sixth Second emerging from non-being into the present moment of my life.

Following this, there was time to revisit the missed count, bring it from where it was archived in the brain, up into consciousness, then travel backward along the knotted string of seconds, then forward again performing recount. Yep, I thought, this is Number Six. Look up.

Then the static line tightened and my parachute popped loud and glorious against the sky. It yanked me upwards, knocking my breath away, but in a few moments I was breathing again, swinging lightly in the cool air, and the plane’s droning was far away, feathering out.

I drifted down in the silence. A silence I’d never heard before. I wished this floating ride could last for hours. But the squares of green and brown came into focus again, with their clean sharp edges, and I knew the earth had never looked this beautiful. I’d never felt so happy, floating in the sky with I-knew-who waiting down there. Then with alarming speed I experienced ground rush.

A single green square swelled outward in all directions, pushing the other colors away, becoming the landing field. The springtime earth approached, spreading fast, coming to meet me with a suddenness I would never forget.

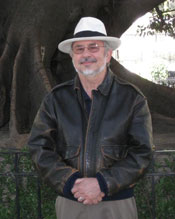

Postscript #1: 41 years after this adventure out on a wing, I traveled to Baton Rouge to attend the wedding of Lloyd Kelly’s daughter, Kristin. During the festivities I met several of Lloyd’s old friends, including Cappy Conners. Cappy had been involved in skydiving in a big way; he had taken one of the first air-to-air photos while in free fall. By the time he’d finished up he had over 500 jumps. After the wedding he gave me a ride to New Orleans, where more fun was planned.

As we drove that raised highway over the bayous we got to know each other a little bit. I told him the story of my first jump, and he listened quietly to the whole thing. Then he smiled and said, “that was me who put you out of the plane that day. And I’m sure it was because… it only ever happened once.”

Postscript #2: Over the years I’ve discussed this adventure with Lloyd many times. He’s always annoyed with my slow performance and especially with both pilot and jumpmaster allowing me back inside.

I could have slipped and the chute accidentally opened, tangling with the little plane and killed us all. Lloyd insists he would have ordered me to jump (and land in a tree or on a highway — who knows where) and if that hadn’t worked he would have pushed me off!

“He should not have let you back in, way too dangerous—no way would I have let you back in.”

Something of a nail-biter, a great vicarious adventure from one who enjoys a bit of parasailing with my grandson. Enjoyed it very much!

Andrea Walker