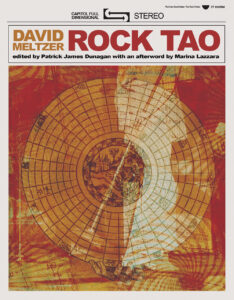

Rock Tao, 173 pages, published by Lithic Press, 2022, edited by Patrick James Dunagan with an afterword by Marina Lazzara.

Rock Tao is a high-spirited and engaging, funny and wise, philosophically and socially astute collage of poetry, song lyric and prose commentary that explores how Rock & Roll set the American musical imagination on fire and awakened a traumatized post war generation through the fifties into the soul-seeking turmoil of the sixties. The late David Meltzer, master poet and improviser, lets us experience how Rock and The Rock Concert, drawing on their Dionysian roots, bloomed into a sacred Rite echoing ancient archetypes. He firmly places our Rock & Roll as an uniquely important creative force within the continuum of mankind’s multicultural genius and heritage.

“Bob Dylan as Orpheus whose large fame can be likened to a race through Hades;

Chuck Berry as Orpheus in the night-world of race warfare & sorrow.

The Maenads, the Bacchae are enacted by the [. . .] followers, the fans, the fanatics” (Meltzer 26).

Rock & Roll turned us on and Meltzer portrays the big reasons why, showing how it rose from a larger need to acknowledge denied social realities, how it gave voice to a generation struggling with the Vietnam war, racial and social injustice, political assassinations, changing sexual perspectives, and how a whole generation sought in it authentic spiritual experience in the face of American hypocrisy.

Meltzer revered the present moment as a Portal into man’s timeless spiritual quest. America, 1965, was his. We are extremely lucky that 50 years later, and six years after David’s death, this book has miraculously come to light. It is a culmination of his personal journey back then, his two year immersion into pop culture informed by years of intuitive scholarship and musical/poetic practice. At the same time he was one of the most important poets of his generation, Meltzer had several bands of his own, including a bluegrass band, and produced three albums, one under the Vanguard label. His lucid and prismatic lens poetically reveals what was really going on in that historical moment and, through astonishing implications, in our own.

“. . . popular culture reveals more than it conceals about the condition of our souls, of my soul.

I began examining what is famous in America as a way to sight those archetypal inventions peculiar to the land” (26).

In the early 60’s, sacred traditions operated throughout the profane, as broadcast on AM radio in 1965. We hear Orpheus’ lyre strum over the popular airwaves of radio stations KDIA (Black Rhythm and Blues), KYA (Top Forty, “Boss of the Bay”), KEWB (Pop Forty, innovative programming) and KFRC (Pop Forty) straight into the heart of America’s teenagers. Anyone could catch these sacred fragments, often unwittingly snuck between the chaos of commercials, sponsors presumably too intoxicated with revenue to realize music’s revolutionary implications. Rock & Roll was teaching a generation how to dance.

A note on the collage form

In her afterword to Rock Tao, Marina Lazarra shares insight into Meltzer’s intention when he chose the collage as his form for this book:

“In conversation with David, the writer and educator, Christopher Winks, referring to David’s editing of the anthologies Birth, Death, Reading Jazz and Writing Jazz, he describes how ‘You’re making a new work out of all those quotes.’ David responds, ‘True. I was inspired by Walter Benjamin’s desire to ‘write’ a book by gathering texts together that told the story he would discover in the collage’” (Lazarra 63).

She further points out that “that no matter what form [David’s writing] takes it is a collage of perception” (62).

Meltzer’s incisive commentaries throughout Rock Tao show this thwarting of linear perception as it comes to us in traditional narrative. People often do this on their own. They read a book as a collage, despite its author’s intention—flipping pages, getting a take on it in snatches, especially when first checking it out. And even after they’re committed to reading it they deal with interruptions, impatience, failure of the book to hold their attention, their own distracting moods, and continue to flip around. This defies the normally intended development of a book, fiction or nonfiction, and yet it’s in tune with our fragmented times. We’re conditioned to it, through dreams if nothing else. From Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, through Eliot’s The Wasteland to Burroughs’ Naked Lunch we’re used to seeing life reflected as a shattered mirror. Its structure automatically frustrates linear time by shifting speed unexpectedly, switching voice and points of view without warning. Thus the chaos of the 20th and 21st centuries is caught in time’s relativity. In our time, after over a century of chaos and upheaval, the collage makes sense.

How then do you read a book that is a collage, such as Rock Tao, that nevertheless develops a narrative line? The key lies between what’s juxtaposed. Collage itself forces readers to meditate on why one thing is placed next to another. The intervals between selections provoke implications readers have to put into their own words. They’re like synapses the mind leaps over to reach thought. In this sense Rock Tao is a workbook, an interactive text. For example, Meltzer illuminates how sixteenth century Paracelsus articulates what Chuck Berry makes us feel.

“[Music] is the remedy of all who suffer from melancholy and fantasy, disorders that ultimately make them desperate and solitary. But music has power to hold them in human company and preserve their minds [.]”

— Paracelsus, 1500’s

“—As I was motivatin’ over the hill,

I saw Maybelline in a Coupe de Ville

Cadillac a-rollin’ on a open road.

Nothin’ out-runnin’ my V-8 Ford.

Cadillac doin’ about 95.

Bumper to bumper, rollin’ side to side.

Cadillac and Ford up to 104.

Ford got too hot and wouldn’t do no more.

It got cloudy and started to rain.

I tooted my horn for the passing lane—

The rain water poured all under my hood.

I knew that wasn’t doin’ my motor good.

— Maybelline, 1957

Meltzer’s commentaries, his incandescent mind, wide erudition, talent for sharp, economic description and a restless, ecstatic but dogged temperament are at work throughout. Consider this comment and the juxtaposed citations that follow. First, a beautiful Meltzer commentary:

“Time is memory of it. Music is time: a theme fragment, a few sung words, & one remembers a specific moment gone. Time is evidence of loss. Song reduces the collective dream to the most recognizable substance. What is complex in time, the form of a time’s dream, is partially known in songs. Time is realization of destruction: it is also the awareness of creation’s process. The heart needs regular demolition. We submit to the heroic because the heroic is what we possibly are. The song challenges nothing. It fills in the gaps. It’s a tool for the creation of memory.”

Then this from Mercea Eliade:

“ . . . the basic experience is ecstatic, and the principal means of obtaining it is [. . . ] magico-religious music. Intoxication also produces contact with spirits, but in a passive and crude way . . . the use of drums and other instruments of magical music is not confined to séances. Many shamans also drum and sing for their own pleasure; yet the implications of these actions remain the same: that is, ascending to the sky or descending to the underworld to visit the dead.”

—Mercea Eliade’s Shamanism: Techniques of Ecstasy (48)

Next Johnny Rivers:

“—I can heal the sick and raise the dead

I can make you little girls talk right out of your head

I’m the one, yes, I’m the one, I’m the one

I’m the one, the one they call the seventh son” (47, 48).

In addition to thematically related quotes such as these, Meltzer juxtaposes vivid descriptions of concerts and performances. This one describing a James Brown performance shows how contemporary performance theatre and transformative shamanic practices share the same psychological root:

“Brown sings a song with a full comprehension of the Book of Gestures: all the mudras & bandhas essential to the movement of his body & the motion of song. Tie loosened, coat thrown to the floor. Gangster Cagney stances. Sweat forms early beneath the rise of his teased turret of glistening curls. The cameras close-up to his face to follow song’s agony: sweat, muscled neck wide with the efforts of expelling song. Then Brown sings his first big hit (1956)

Please, Please, Please . . .

He falls to his knees holding the mike in his hands like a lover & wails without restraint in time with the beat. One of the Famous Flames (Bobby Byrd), who earlier picked up Brown’s discarded sports coat, picks Brown off the floor, takes the mike out of Brown’s hand, sets it a right, then leads him tenderly off stage, draping Brown’s checkered sports coat around heaving shoulders. Brown looks ahead, fierce tragedy in his eyes.

Suddenly Brown snaps around, rushes back to the mike, grabs it like an old-time movie-star grabbing a fluttery heroine & bending her back to kiss her. He falls to his knees & begins screaming & sobbing, louder than before.

Baby, you’ve done me wrong,

Took my love and now you’re gone

Baby, take my hand.

Please, please, please, please, please don’t go!

Again he is picked up off the floor by Bobby Byrd & led off-stage:

Byrd’s face & bearing revealing brotherly sympathy & compassion” (Meltzer 115).

Not quite narrative, though you feel the currents under the boat, Rock Tao is metaphysically picaresque in its juxtapositions, a Tristram Shandy take on a chaotic moment in world history, seen through its pop culture. But it’s not a book of endless digressions to avoid resolution, like an old river getting slower and slower, bending back on itself in ox-bows as if to stave off its eventual disappearance in the sea. There is a narrative thrust, a strong thread that answers the essential question of why Rock & Roll was a necessary and ecstatic experience. By reuniting the mind and body it recovered the dance. It restored our zest for living and helped us embody our wholeness as human beings. Those decades were a high point, exciting, full of danger and uncertainty and the art that came out of them made it clear that nothing will be the same again. All efforts to turn back the clock to before Chuck Berry are futile.

In Rock Tao James Brown the pop artist comes off performing a shamanic act, changing the stage into a temple. Although he sings from the pain everyone feels, the voice rises, as with Otis Redding, from one man, sittin on the dock o the bay.

Meltzer began his book with a question that he resolved with a prediction:

“Is there a way to penetrate that unknown core fixed in America’s heart?

If there is, it will be the same path leading to the unknown center of my own being” (28).

The top’s down, Cadillac revving, and the radio’s on . . .

The idea of James Brown as a shaman makes perfect sense.