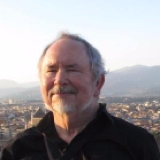

In response to this issue’s call for submissions, the statement “we invite authors to reflect on how the influence of previous generations shaped your identity” set me thinking about a key moment of conversation with my father. This would have been about 1955, when I was twelve.

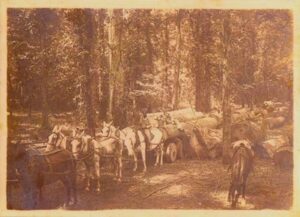

My father was a sawmill man in Mississippi, who had been raised by a sawmill man in Arkansas, who had been raised in the woods by a logger. My father loved everything about his work, from the forests to the milling to the lumber. I was in awe of him, and of our family’s stories about generations in the woods.

My grandfather, Luther Wallin, Sr., eventually known as “Mr. Luther” and to me as “Papa,” reclining on his logs in a suit, about 1910. Notice the size of the logs on the ground near his shoes. Mules would pull box-wheeled wagons through the mud. In the foreground Papa’s horse is saddled and waiting. The man riding the mule carries a shotgun for squirrels to feed the crew.

I grew up with the smell of fresh sawdust and the sound of the bandsaw. I listened to the way men spoke to my father, and he to them. He was calm, even-tempered, fair, and enjoying himself.

When I was nine years old my dad introduced me to old school hunting. That is, the main thing is being in the woods, being alert to every sound and movement, and when you take an animal such as a squirrel, make sure you will personally clean, cook, and eat that creature. Never kill any animal you don’t plan to eat, and never leave a wounded animal behind.

Although he hunted occasionally, mainly quail, he wasn’t very interested. He just wanted to show me the right way forward. I’m sure my parents were surprised by how immersed I became in two things, hunting and religion. I was raised on Baptist sermons about Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac in the wilderness. Prophets would appear from out of the wilderness to accuse a king of misbehavior. And Jesus, after his baptism, went into the wilderness to fast for forty days and forty nights. After that time he was hungry, and the devil appeared and said, “If you are the son of God, turn these stones into bread.”

At the age of seven I was thinking about these things in my parents’ garden. In addition to flower beds and fruit trees there were large oaks and the tallest pines you could imagine. And just beyond our garden there was a hardwood forest of about 25 acres which someone had bequeathed to the town as a park. I studied the wildness of bees, the battles between streams of red and black ants, and I hid to watch long lines of quail pecking along in the grass. There were two oaks almost identical, and I tried to form a question about this: how could there be two things that somehow were the same? When I asked about this my parents “looked at me funny.” I would have to wait until I reached college to discover that Plato was interested in that question, 2500 years ago.

I was that kid who believed what his parents told him about the Bible, and who tried to imagine events involving Abraham and Jesus, Satan and Angels, taking place in the woods—overwhelming to a child—behind my house. A lot of hunting also took place in the Old Testament, which I read every night.

By college I had worked in the logging woods and the sawmill, and with two friends I had built fences through the swamp to mark land lines.

It was while hunting alone in our forest in the Tombigbee River bottom that I wrestled with whether I had a call to preach. Wilderness had two different spiritual dimensions, one just the magic of nature, the other conjuring the nearness of the Garden of Eden, of Noah’s Flood, of Isaac’s sacrifice, and of the hunter Esau’s deception of his father by using a freshly killed deer.

In the woods I watched otters rolling in play, foxes running up trees, a turkey vulture laying her giant egg on the ground inside a hollow tree, a pair of does following bobcats, and other wonders hard to believe.

Another of my father’s lessons was about Native Americans. “They were treated mighty badly,” he would say. “They hunted to survive, not for sport.” This statement was powerful medicine for me. Hunting was normal in our culture, as well as in the Bible. Nobody in the 1950s in Mississippi said it was wrong to kill an animal. Yet my father implied not only that it must be done with minimal suffering, and that one must always eat one’s kill, but also that there was something wrong with sport hunting.

I appreciated my family’s forestry and sawmilling activities, yet I didn’t want to follow that path. One day my father said something to me that—in retrospect—seemed to magically open a door of understanding. We had been discussing the widespread practice of clear cutting a forest. “Clear cutting is wrong,” he said, “because the animals need a home, too.”

As a parent, you never know what will change the course of a child’s life. A single negative remark can leave that child struggling for years. My father practiced something called selective harvesting, in which all the trees of a certain size (or smaller), say 24” in diameter four feet above the ground, are spared so that the forest can recover relatively quickly. Of course if you love a forest “relatively quickly” means long miserable years. Yet this is infinitely better than clear cutting.

It wasn’t the technical aspect of this matter than meant so much to me. He was saying there was something ethically wrong with the way his entire generation was treating both forests and animals. These two issues were linked. And he was speaking as one who made his living from the forest.

If we could question such things, and make our own ethical decisions, and change practices within our local, humble, domains, then we could apply critical thinking and ethical change to issues and events on a larger scale.

I don’t think he meant for me to go that far. And maybe it was his actions through time more than a single statement that allowed me to break some generational expectations.

Having a progressive thought about forests was one thing; being able to do something to protect them was another. I entered college in 1961. That was before the conservation writing of Rachel Carson, John Muir, and Aldo Leopold had made its way into Philosophy Departments. And it was six years before Wilderness and the American Mind by Rodrick Frazier Nash was published.

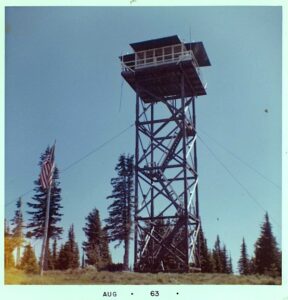

During college I worked for the U.S. Forest Service in Idaho, fighting fires, clearing brush from fire-prone mountainsides, and I spent one glorious summer in a lookout tower.

Later I would be told that the U.S. Forest Service was guilty of the worst clear cutting imaginable. I wanted to go back and visit those mountains covered in tall Douglas Fir trees. One of my buddies had done that. He said, “Don’t go back. They cut every last tree.”

When I went to grad school in Philosophy, Ecological Ethics were not yet taken seriously.

When I studied fiction writing at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I began to write about my woods experiences, and ten years later published my first novel for young people, The Redneck Poacher’s Son. This took on deer hunting, family violence, and characters who treated the forest badly indeed.

I was coming to terms with the fact that wilderness could be felt as authentically wild, while at the same time having meanings that were cultural inventions. This applied to hunting, or course, but also to one’s understanding of Native Americans whose forest homes had been perceived as a “wild frontier” by whites. My ancestor Thomas Walling had taken part in King Philip’s War in 1675 in New England. In the 1700’s several ancestors had been market hunters for deer hides in Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky.

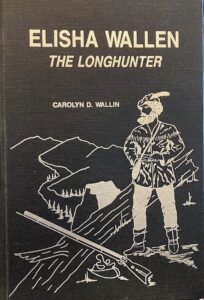

Elisha Wallin II, The Longhunter, was my 3rd Great Grandfather John’s brother. The brothers and their father, Elisha I, were all longhunters but Elisha II became famous for leading others including Daniel Boone on hunts up to 18 months-long in the wilderness.

There were many conflicts with Native Tribes. Family stories say Elisha I, as an old man, was the first white “scout” scalped in Harlan County.

Mary, the first wife of my 3rd Great Grandfather John, was killed and scalped at the spring near their cabin in Virginia. The following year John married Elizabeth Roberts, probably Mary’s sister. One morning a Cherokee raiding party knocked on their cabin door. When Elizabeth opened it they fired and wounded her. She slammed and barred the door. Her husband jumped out of bed, took his rifle down, and killed one of them, probably firing through holes between the logs. He killed two more and the raiders left.

Their leader had been Bob Benge, celebrated as a hero of the Cherokee resistance, and described by the whites as a “forest bloodhound.” Elizabeth was my 3rd Great Grandmother. One of her and John’s sons, Jessie, took part in the removal of Creek Indians from Georgia during the Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

My fourth novel, In the Shadow of the Wind, explored this tragic period in American History.

In an article in Educational Horizons, James Briggs discusses these two novels in detail, and reports on using them in his history classroom. That essay is on my website, here: https://www.lukewallin.com/reviewyan.htm

Writing books for children and young adults I explored many versions of wilderness. My father had pointed to the difference between indigenous subsistence hunting and sport hunting, and I came to realize how deep this divide can be. In my fifth novel, Ceremony of the Panther, I explored a 1980s case in which a shaman sacrificed a Florida Panther in order to obtain healing medicine. My fiction imagined the conflict between traditional Mikisuki medicine and the government’s wildlife biology approach to understand what a panther is, and what a human being is. People speak of Native American history as if it were past. But it’s a set of 10,000 year-old cultures that are alive today. My book follows 16-year-old John Raincrow as he tries to find a way between the science he respects and the father he loves.

For myself, the day came when I never wanted to kill another living creature. Just as love of the wilderness and of hunting came upon me mysteriously as a child, just as mysteriously a renunciation of all killing came upon me as an old man. However, there was a sharply rational component to this. It was not killing an animal for food that I rejected, it was enjoying the killing. This is the secret at the heart of hunting that dare not say its name. My friends and I had tried to minimize the significance of killing within our hunt, by keeping to one-deer-a-year, and carefully field dressing, packing out, and eventually cooking the venison for our families. We had emphasized tradition, love of the forest, camaraderie, woodcraft, our simplicity of technology, and the fact that we protected the woods through using it as we did. Still.

This kernel of the matter had been there all along, but in the generations of my ancestors men were expected to kill in socially approved circumstances, such as war, and hunting was often seen as psychological preparation for young men or even children. In the 1960s war resistance produced large numbers of young people who espoused conscientious objection to all killing of human beings. This effect was amplified by demographics. Young people in the U.S. had the numbers to embolden standing up against the draft, and conscientious objection became a respectable philosophical foundation for this. This generational change put old assumptions about killing animals under a new spotlight.

None of my children or grandchildren ever wanted to hunt. My family said “no more venison.” Sport hunting in recent decades has become, instead of an unchallenged quiet practice, a gross spectacle of TV shows featuring trophy bucks being slaughtered on camera, sponsored by companies that sell feed and feeders (to make wild deer tame), portable shooting towers (to make wild hunters tame), and that valorize “hunting ranches” where anyone for a few thousand dollars can fly in, be placed in a tower with a guide, and allowed to use binoculars to pick and choose among bucks especially bred and fed to produce massive antlers. Where is the sense of accomplishment or “fair chase” in this? Corporate hunting culture feeds a mania for large racks, with magazines featuring what one of my pals calls “antler pornography.”

But lest I be too hypocritical: every style of hunting involves some play acting, some pageantry, and some self-delusion while performing. We pretended to be mountain men. For a while I even hunted with a Hawken Rifle like the one used by Robert Redford in the film Jeramiah Johnson. Most hunters have adopted a style that came to them through culture, and most of them value being out in the woods with friends, having an intense goal, getting away from the constraints of life under late capitalism for a few days a year, and having a set of antlers on the wall to remind them of these good times.

My father was more progressive than I about hunting, from the beginning. But things are never linear. He was the sawmiller, while I pursued conservation as a professional writer and teacher. I hunted, but in managing for the lightest footprint, I protected an ecosystem for half a century.

Doing the solitary work of writing novels I researched environmental and anthropological questions on my own. Then one day I learned about a grad program nearby, a master’s in Regional Planning.

In this program I learned much about how to work toward conservation goals with others.

My account of one memorable project was published in Sisyphus:

To recap my family story: my father gave me the opportunity to form a generationally different way of thinking about wilderness and conservation. But how was I to apply it? Most often through writing and teaching. I wrote Conservation Writing: Essays at the Crossroads of Nature and Culture, and with Irish geographer Anne Buttimer, I contributed to and co-edited Nature and Identity in Cross-Cultural Perspective.

But how about actual protection of living creatures, forests, lands, and rivers?

Since I wasn’t a professional manager in those areas, I took volunteer opportunities as they came along. I helped several people in achieving selective harvests of their timber, in other words, no clear cutting. I worked with a land trust to help donors of development rights through political headwaters. With other community members I spoke up to pressure a city toward restoring a neglected urban stream, and to desist from creating inhumane traffic flows. These were modest achievements to be sure, but with conservation work every day, at every scale, counts. The developer only has to win once, in order to wreck nature. A conservationist has to win every time. A wild area is only saved for now, and remains vulnerable.

My wife Mary Elizabeth Gordon has been my partner in all this, from writing books to boots on the ground in the field. This summer we let our grass grow into meadows, surrounding our wildflower gardens, to offer more habitat to songbirds, bees, dragonflies, and bats. The creatures are busy out there every day.

Luke, I very much enjoyed your essay; with it’s unique blend of history, culture, identity anc ethics. This blend is what true interpretation is and an asset when teaching others to engage their environments. Story telling!

Thanks for sharing, Cole

Hi Luke,

Just came across your gorgeous piece in Sisyphus. Lovely writing and shared memories!

Love, Susan

I wish we could all work together to protect the beauty and the beasts from the mobs of devilish humans.

I dream of a time long ago, before the harm. A time of inspired work and good natured play… A time when people played hide and seek with staffs and imagination.

When all was unknown but for our love.

What made us hurt so?

What made us forget the basics, the simple things?

Why can’t all nature freaks unite in the silence of awe?

Why can’t we leave the world speechless?

Why can’t we communicate with chirps and tones?

“The language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical: little is said, but much is meant and understood.”

-Gilbert White