Why the progressive movement has stalled.

I. Nominal and Material Progressivism

Both Adam Smith and Karl Marx believed in progress.

I’m concerned with action and results. If we don’t impact material change, what is the point? A results-oriented concern begins with clarifying what we mean by progress and progressivism. Consider this essay an open-ended exploration of progress rather than a definitive statement.

The question, therefore, is what do we mean by progress? How do we understand it? How does it operate? How does progress correspond with progressivism? These questions have become important because progressivism has encountered an internal impasse. It has become mired in internal conflict.

In a June, 2022 column in Politico entitled “The Left Goes to War with Itself,” John Harris summarizes the current state of internal dysfunction:

The fight is becoming bitter. On one side are people who believe in what can be thought of as a unified field theory of political and social change. Diverse issues, from climate change to abortion rights to racial equity, are seen as intimately interwoven, and progress on one priority will only be achieved with simultaneous progress on other fronts. On the other side are people who don’t much buy this theory — and roll their eyes impatiently at theoretical arguments of any sort if they stand in the way of practical results on the specific issues they care most urgently about.

Progressive communication has broken down. The ability to develop a shared understanding is distracted by unproductive and divisive language. Conversation and discussion can descend into unintentional language games. We burden ourselves with awkwardly loaded terms like “woke” and “identity politics” and “privilege.” Emotions run hot on nearly every progressive front, and many people have become increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of progressivism. This essay will ask us to reconsider what we mean by progress and to reconsider how progressivism operates.

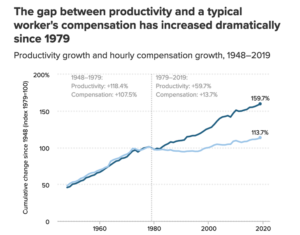

My argument is this: progressivism has bifurcated. It has split into two camps, and the split has handcuffed the impact of Progressivism. The nature of the split is fundamental, and it implicates the way progressives think, communicate and act. We might use the word schism, which implies the separation of one church into two. While progressives share many core beliefs, such as equal rights, economic mobility, access to healthcare, and the protection of natural resources, the ability to mobilize action has stalled. We could look at middle class wage stagnation, for example, as just one case of the ineffectiveness of progressive movement.

If we were to examine the effectiveness of public education or access to affordable healthcare in the United States, it wouldn’t be a pretty picture either.

II. A Schism

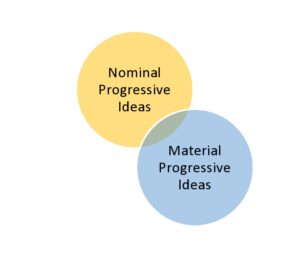

This schism is fundamental and cognitively structural. In one camp we see “nominal progressivism” and in the other camp we see “material progressivism.” Nominal progressivism is concerned with linguistic understanding and verbal criteria, while material progressivism is concerned with quantitative understanding and verifiable criteria. Nominal progressivism is concerned with naming, and material progressivism is concerned with measuring. This difference creates fundamental cognitive gaps in understanding, which then lead to an inability to take effective action. Why? Because the two camps cannot agree on what effective action means. In fact, they don’t seem to have the desire to communicate about it.

The opposition between nominal progressivism and material progressivism presents us with what appears to be a dichotomy: “it’s this or it’s that.” Many critical theorists will object to the use of a dichotomy as a way to understand a particular topic. They will say, “your dichotomy is a hierarchy in disguise that reveals a hidden bias.” But this is more complex than a simple dichotomy. I prefer to think of it as two categories of thought with distinct criteria, two different but connected sets of members. And this distinction changes what we are talking about.

We can identify the contents of the two categories (nominal progressive ideas and material progressive ideas) and compare them. There will be, for example, members who are in both categories. In other words, it’s more like set theory. If we call these two sets, set A and set B, we can look at A ⋃ B. (all members of both sets) and A ⋂ B (the members that are in both sets). We can also identify the members who are in set A and in set B but not in the intersection, also known as the disjunctive union or the symmetric difference.

This may seem like an abstract mathematical digression, but it’s central to the critical difference between the “nominal” and the “material.” Why does this matter? It matters because one important way to think about nominal categories is to attempt to quantify them, to take a material approach to defining what they mean. If we are to create and name categories like nominal and material progressives, we should also define them in material ways. How else are we to be clear about what we mean?

As Jung points out, “there is no consciousness without discrimination of opposites,” and “there is no position without its negation.” Or in other words, conceptual opposites spark our ability to think at a primordial level. We can also think of this not as a dualism, but what Dewey would call “two phases of a single action.” Either way, the categories of nominal and material progressivism provide us with a method to make sense of what’s happening around us. I would go further and say that while the “dualism” of nominal versus material is useful as a way to understand the schism in progressivism, ultimately we must transcend that dualism. We need to strike the right balance between the nominal and the material. We want to learn to operate in the dynamic intersection. We could borrow a term from music and think of it as a cyclic progression.

Finally, one could easily make the case that progressivism can be arranged into not two, but instead a wide variety of different segments and groups, each with its own unique vantage point. That case, however, is the case for someone else to make. My concern is that the split between nominal and material progressivism has created a divisive impasse within a group of people who are otherwise largely aligned about the direction of civil society.

III. Two Examples

Recently I was having a casual conversation with my sister-in-law who teaches in the public school system in Oakland, California. We were discussing terminology and the question before us seemed simple: is there a meaningful difference between “homeless” and “unhoused?” This categorical distinction had recently become a source of public discourse. We found ourselves discussing the potential for terminology distinctions between K-12 students who are categorized as “homeless,” and how that compares to the students who are categorized as “unhoused.”

Our questions hovered around the meaning of the two terms. Does using “unhoused” rather than “homeless” provide some useful specificity to how we classify these students in the school system? Does this terminology address some kind of harmful stigma? Does this terminology illuminate some underlying material differences and thus point us toward something we could do about it? After going around and around on this topic, we landed nowhere.

In an essay by Architectural Digest, Nicholas Slayton writes that “a related term to homelessness, the homeless, has begun to be seen as othering. In May 2020 the Associated Press updated its stylebook to focus on “person-first” language; it said not to use the homeless, calling it a dehumanizing term, and instead use terms like homeless people or people without housing.” The article goes on to include the view, albeit briefly, that would appeal to an unapologetic material approach: “There is the argument that in some ways, the language does not matter; material solutions to homelessness do.” In the end, it’s unequivocally clear that both matter.

The conversation moved on, and we talked about the nominal difference between the terms ESL, or English as a second language, versus “English Learners.” We floated another term: English as a non-primary language. Was that more accurate? Which term is the better way to define English proficiency in the school system? Aren’t all K-12 students English learners? The question ultimately was, does using a different term actually make a difference? Again, there was no clear answer, and she is a bilingual teacher in heavily ESL/ELL communities.

This kind of terminology has significant material impacts, including program design and funding allocations. Whether a person is classified as ELL or ESL can correspond directly to programs that they can take advantage of to learn English. In an article by the National Council of Teachers of English, the authors state “the shift in terms has a great deal to do with both policy and issues of identity for students. For example, up until the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2001, most educational documents referred to these students as bilingual or ESL, both of which acknowledge that English is a second language and that a student has a first language as well.”

In many ways, this essay is a terminology discussion. There is a non-trivial relationship between terminology and material categories. Terminology discussions shape how we think about problems generally and social problems in particular. Furthermore, the terminology we use defines the characteristics of the category which then determine how we identify ideas as belonging to one group or another. In the case of “unhoused” versus “homeless,” terminology represents an attempt to understand the characteristics of a certain group. But when we focus on language and labeling, the discussion revolves around the words, and for nominal progressivism, the discussion tends to get trapped in language. We often find ourselves caught in an Orwellian dance around which term is acceptable and which term is objectionable.

Then, the conversation changed. I had seen some recent statistics on homeless/unhoused K-12 students, and the discussion moved to the numbers. The federal government’s department of education estimates that there are approximately 1.3 million homeless/unhoused students in the K-12 school system nationwide. California leads the nation in the shameful statistic with well over 300,000. It’s a shockingly large number. The hard data on homeless students changed our discussion to a “material” understanding about this social problem, a quantitative framing of the problem. And whether or not these students are classified as unhoused or homeless, the large number of homeless/unhoused children is an important social problem. The terminology may have a nuanced impact on the discussion of the problem, but it does not address the fact of the problem itself.

It was an informal conversation, but once we turned the topic to the hard numbers of homeless/unhoused students, we started talking about material ways to allocate funding and resources. We discussed the ratio of teachers to students and classrooms, the ratio of staff to teachers, and the salary of teachers. We discussed the lack of structural readiness of school systems to adequately support the challenges of these students, as well as the other students who are in classes with them. While we acknowledged that we weren’t experts in what works and what doesn’t, the conversation had changed. We had shifted from a nominal discussion to a material discussion. It became clear that without a material change to handling homeless/unhoused K-12 students, the terminology didn’t really matter.

In a formal setting, we could take the discussion about these definitions in a material direction. We could quantify the difference. We could use the definitions of “homeless” and “unhoused” to create two sets of students based on the different definitions, one set that contains all members from the “homeless” definition and one that contains all members from the “unhoused” set. We could then compare the two sets to see if there was a material difference. If the students in each set were essentially the same, we could say that the “nominal” difference made no “material” impact. If there were a difference, we could then consider the two sets more closely, compare them, and consider the union and the intersection of those two sets. Furthermore, we could start to consider ways to make an impact on the students in the group, an impact that we could measure and improve over time.

IV. Progress

John Stuart Mill believed that people are inherently progressive, and that “the perpetual obstacle to human advancement is custom.” The past haunts us and refuses to let go. So what do we mean by progress? Simply stated, progress embodies the idea that “science, education, and political freedom will bring social progress” (Cahoone). Progressivism implies progress, but it is not the same thing. Progressivism is the politically and socially active behavior of the commitment to progress. Progressivism embodies a practical philosophy that applies to civil society. It is not a philosophy of ontology or teleology or epistemology. It is a philosophy of practical applicability and how we live in a civil society.

It must be said that not everyone believes in progress. There are countless traditionalists and fundamentalists who still believe that the past represents an ideal time, and that the future is a continuous degradation of that better past. But this paper does not concern itself with such traditional thinking. I am concerned with the split between nominal and material progressivism.

This concept of progress (and progressivism) is not necessarily ideological. In other words, it doesn’t have to be tied to a particular political philosophy. It’s worth pausing to explore this idea – the idea of progress does not necessarily adhere to a particular economic or political ideology. At its most fundamental level, the belief in progress merely states that we can make the future better than the past through our actions. While the definitions of progress will surely differ depending on our ideology, we don’t have to be a libertarian or a socialist or a communist or capitalist in order to believe in progress.

As I stated at the outset, both Adam Smith and Karl Marx believed in progress. There were, it’s safe to say, significant differences in their definitions of progress and how to get there. Much has been written on the similarities and differences of Smith and Marx, and I won’t rehash it here. But it might reflect the most important departure between nominal progressivism and material progressivism. Material progressivism does not necessarily concern itself with the particular ideology required to achieve progress. Material progressivism is concerned with material achievement. Nominal progressivism is concerned with language and terminology. Understanding the interplay between these two is the purpose of this essay.

How do we define progress? How do we quantify progress? These are easy questions to ask but not easy questions to answer. The very discussion with others about how we quantify progress will yield surprising results almost every time. For the sake of this discussion, we might consider using the human development index as one means to measure progress. It narrows the focus to three vectors for its measurement.

- a long and healthy life, as measured by life expectancy at birth;

- knowledge, as measured by mean years of schooling and expected years of schooling;

- a decent standard of living, as measured by GNI per capita in PPP terms in US$.

To these three metrics we might consider adding specific civic abilities, such as

- the ability to hire and fire your leaders through free and fair elections;

- the ability to enjoy a free press;

- the ability to express yourself and your opinions openly.

There are other measures that we could consider, but these six measures are practical, empirical, and easy to understand. They can be measured, and we can confidently presume that Progressivism aims to improve these material factors. But it is the exchange of ideas about how to materially quantify progress where we force a deeper understanding of what it means. To define quantifiable criteria forces us out of the trap of language games. For example, how would we quantify “the ability to enjoy a free press?” Engagement in that material discussion will doubtless yield many surprising directions.

Furthermore, there is a vital entanglement between nominal and material definitions. This is the crux of the matter. The idea of nominal definitions, on one hand, indicates the practice of defining something, naming it, so that it can be verbally distinguished from other things or categories. This typically means using other words to describe the words you’re defining. A nominal definition tends to be qualitative, and it provides verbal characteristics. The nominal definition does not get at its underlying material structure or makeup.

A nominal definition tends to be qualitative, and it provides verbal characteristics.

The material definition, on the other hand, is quantitative. It attempts to identify the measurable, empirical understanding. Can it be counted? Does it have weight? Does it have size? The material definition forces us to define the measurable contents of the nominal definition. The critical point here is this: the nominal definition guides us in defining the material definition, and the material definition brings us back to clarifying the nominal definition. The two are mutually entangled in a cognitive dance. This brings us back to the musical notion of a cyclical progression.

The material definition, on the other hand, is quantitative. It attempts to identify the measurable, empirical understanding. Can it be counted? Does it have weight? Does it have size?

Unlike the nominal definition, the material definition attempts to get at the structure and the measurable characteristics. As an example, if we say that “the glass is half-full of cold, clear liquid,” we’re using a nominal definition. If we say instead that “the glass contains 0.5 liter of .9% saline solution at 5 degrees Celsius,” we’re using a material definition. A material definition doesn’t necessarily need to be scientific. It could also refer to economics, mathematics or other material resources. A nominal definition of wealth might express that someone is rich, and the material definition might say that that person possesses $1 million in liquid assets. But someone else might disagree and say you’re not really rich until you’re worth more than a billion dollars. It is at this point that the definition of rich takes on material meaning.

In order to avoid confusion, I will add a brief clarification here on the difference between materialism and a material definition. While the philosophical idea of ‘materialism” and the idea of a “material definition” are related concepts, they are distinct in their scope and application. Materialism is a broad philosophical belief that holds that physical matter is the fundamental reality of the world, while a material definition is a tool used to define terms and concepts based on physical properties. The focus in this paper is on the application of a material definition.

V. Impasse

To be sure, the language we use shapes the way we think. This is a well established area of exploration for those who study linguistics and cognitive science. Some cultures have no words for left and right. Others have a very small number of words for color. “People who speak different languages will pay attention to different things depending on what their language usually requires them to do,” says Lera Boroditsky, a cognitive scientist. Nominal progressivism tends to emphasize linguistic differences.

The same can be said of thinking quantitatively. When we attempt to understand something using quantitative tools and techniques, it changes the way we think. It forces us to engage techniques that we might call practical or pragmatic. It forces us to use numbers rather than words, calculations rather than sentences and paragraphs. As brain science matures, and we understand more about how the brain works, we can now examine, visualize and quantitatively measure the differences. Brain studies show that we use different parts of our brains when we think qualitatively versus quantitatively.

One of the biggest problems with this split between nominal and material progressivism is the inability to achieve a coherent understanding of actual progress. Nominal progressivism tends to be energized by terminology and language and that energy avoids the practical tools of material or quantitative analysis. Material progressivism is not necessarily concerned with ideology or terminology. It attempts to understand the inner workings of a problem in order to find the quantitative strategies that will change the situation. Furthermore, nominal progressives tend to be more ideological whereas material progressives are more practical. This important difference, which is largely unrecognized by most progressives, often pits them against each other causing friction and misunderstandings. They don’t have a common language and they don’t know how to define a unified direction. They will face off against each other in disagreement and not understand why they aren’t communicating.

Language sets the ball in motion. Progressive efforts start with words, labels, and ideas rooted in language. Even if we are to make sense of any quantitative assessment, we use words. We do not start with numbers and measures. We start with conversations, with sentences, utterances, words. If we are to agree to pursue any kind of material understanding we begin with a nominal understanding. Furthermore, any progressive pursuit ends with language. The entire effort is bookended by language. When we sit down to assess how we performed, to know if the policy or the investment or the experiment was useful, we engage in language. In the end, the nominal bookends the material on both ends, but the nominal without the material can be like bookends with no books between them.

VI. Language Games

In the 20th century, Western philosophy became increasingly obsessive with language. The practice of what I am calling nominal progressivism follows closely on the heels of this obsession. 20th century philosophy endlessly and furiously attempts to understand the relationship between language and thinking. Many of these thinkers attempt to reduce all thought down to language. From Wittgenstein to Heidegger to the Structuralists and the post-Structuralists and the Semioticians and Deconstructionists, 20th century philosophy became mired in the relationship between language and thinking. One of the representative figures of this obsession is Jacques Derrida, the father of what is known as Deconstruction. One of his central critiques is the idea of logocentrism, which claims that humans cannot help but obsess around words, signs, symbols and what they mean and what they don’t mean. Logocentrism means literally that everything is centered around “the word.”

Staying with Jacques Derrida for the moment, logocentrism presumes (among other things) the existence of stable and self-contained meanings in language, where words can accurately represent and convey essential concepts or truths. Derrida challenges this presumption by highlighting the inherent instability and ambiguity of language. He argues that language is a system of differences and signs that refer to other signs, lacking any fixed or absolute meanings. Therefore, the search for a single, fixed meaning is futile and leads to a false sense of certainty. In other words, we dissimulate incessantly about everything. Deconstruction also presents us with a set of tools to dissect and understand how the language that we have inherited can be taken apart to reveal underlying assumptions, presumptions and privileges. These are some of the linguistic hallmarks of what we call postmodernism, and what we also call “critical theory.”

This leaves the idea of nominal progressivism with some serious problems. In the words of Lawrence Cahoone, “Postmodernism may provide the means to critique the status quo, but can it provide the resources for a normative solution? If the postmodern critique attacks every statement that a policy maker or theorist might make, which they can, they could simply unhinge our ability to say or do anything. If we are to change society, this would require justifications of unity, identity and privileged conditions that postmodernism must undermine. Can the critical beast of post modernism be brought to heel?”

We have inherited this deconstructive obsession with language from the 20th century, and we don’t seem to know how to move past it. These linguistic tools provide us with a powerful way to apply critiques to texts, but they don’t provide us with means or mechanisms to move forward in any material way. If we go back to the example of the homeless / unhoused students, we could debate endlessly about the language in and around these concepts and terms, the signs and symbols and transcendental signifiers, and show how the language reveals our logocentric obsessions, our preferences and privileges, but it doesn’t take us forward. In other words, we still have 1.3 million homeless / unhoused K-12 students in United States.

Using material methods does not guarantee success. It’s entirely possible that we could follow the method that I’m recommending and still fail. We might iteratively progress from the nominal to the material in a cyclic progression in order to arrive at some mode of progress, and in so doing devise poor, misleading or unconstructive material criteria and techniques. In other words, applying a material approach doesn’t guarantee that we will get it right. In fact, developing the acumen and the vernacular of using material methods requires practice and development and open-minded creativity.

One way we can lead ourselves astray, for example, is to consider both nominal and material techniques in a realm where we have no ability to make an impact. In other words, it’s important to understand the sphere of influence in which we operate. If we are truly interested in progress, we should consider framing our thinking within a space that we can impact. We might want to ask ourselves, “if we want to make progress in a particular area, do we have the authority and the imprimatur to make something happen?”

VII. Consciousness

In the New Organon, Francis Bacon dismantles the crippled mode of thinking of his time. As he saw it, the mode of thinking was stuck and irrelevant and mired in circular logic. Considered by many to be the father of the scientific revolution, Bacon changed the way we think about how the world works. And he did so with the express purpose of making the world a better place, to unleash the power of creative thinking to remedy the pain and suffering of people. “In order for the mind to remain free and unencumbered, it must abandon the old, accepted ways and embrace a new path of inquiry and investigation.” What I’m proposing ultimately is a method. The term I’ve used here is a “cyclic progression” and that seems adequate for now.

In a recent conversation with my father, we discussed whether or not consciousness could be understood from the standpoint of materiality. Could we take the lens of material progressivism and focus it on consciousness, a topic that is often esoteric and metaphysical? He thought about it for a few minutes and then suggested that we could consider the current mental health crisis that we’re experiencing. If, in other words, someone loses touch with reality, their consciousness is no longer able to adapt to the world around them in such a way that they can function as a member of society. Furthermore, if we were to use the lens of material progressivism towards consciousness, we might measure the rise and fall of significant mental health problems.

This was a completely unexpected direction for this conversation to go. I was surprised and curious. Generally speaking, our discussions about consciousness had centered around topics such as epistemology and faith and Buddhism. But when he applied this new material lens to the question, what surfaced was a a pressing, practical and quantifiable social problem. Of course there are many ways we can think about consciousness, but this redirection toward mental health struck me as materially germane and socially important. It forced us to both reconsider the nominal definition of consciousness as something to be thought about and studied and discussed. It was the beginning of a fine example of cyclic progression.

Timely and on point.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/07/10/seduced-by-story-peter-brooks-bewitching-the-modern-mind-christian-salmon-the-story-paradox-jonathan-gottschall-book-review

More information on homelessness facts

https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/our-impact/our-studies/california-statewide-study-people-experiencing-homelessness

Demian, I was going to start to tell a story here—about my own brush with radical/revolutionary progressive politics and then the life-changing schism I experienced within and through it … in a land and time far, far away from the San Francisco East Bay but still somehow familiar… and the I read Parul Sehgal’s essay you linked above in comment. ::chuckle::

One pebble that coursed through my consciousness, as I read, riveted, through “The Progressive Impasse,” was this throwaway notion: I wonder what Derrida would have thought of large language models and transformer technology! ::chuckle::

Otherwise, here’s a quick riff on your incisive essay — ’tis an excellent and clear distinction on the 2 types of progressives, and the impasse that progressivism finds itself in, never mind that some of the latter are in fact getting practical things done, albeit in that intersection you so beautifully metaphorize as a cyclical progression in music (chess notation: !!!).

But I say the blunt tool of conservative (well, right-wing/MAGA these days) realpolitik, with its relentless focus on ‘othering,’ trumps BOTH the navel-gazing semiotic inclinations of nominal progressives, AND the practical governing that material progressives in power (the Biden wing of the Democratic party, I suppose).

This huge and very real distraction from the other side doesn’t make for much space in resolving this schism you so clearly see in the progressive movement. The leopard can’t leisurely contemplate changing his spots, when there’s a posse of hungry lions trying to steal its freshly-killed impala from it. ::chuckle::

So I experienced this schism in a parallel (but substantially different) way back in my 20s, when I was involved in a radical activist movement to oust the then-dictator of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos. But, pace Sehgal… that’s another (dark) story for another day.

Not too far off, even for the NYT

The Failure of Progressive Movements https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/26/briefing/me-too-black-lives-matter-occupy-wall-street.html?smid=nytcore-android-share