Domains of Freedom: Little Gods and the Era of Hegemonic Freedom

I. Introduction

The tug-of-war over the meaning of “freedom” is the struggle of our time. But in many ways this struggle is hardly new: the meaning of freedom is inseparable from the notion of government. The idea of freedom is, after all, as old as government itself. Who governs and who are the governed? Are the governed free? These are ancient questions. What is new is that the battleground has shifted radically. The new battleground depends on recent changes in language and meaning, and specifically on what we mean exactly by the word freedom. The concept of freedom radiates a primeval power that borders on the mystical. It goads us, it guides us, and it shapes us. But the modern concept of freedom has grown significantly more complicated. For this paper, I will discuss three categorical definitions of freedom that are vying for prominence, and one of them represents my own conjecture. These three definitions (domains) draw their rhetorical license from the mystical power of freedom, but they depart from one another in practical ways that materially impact the rights of people, the function of global economics and the emergence of new levels of personal power.

Furthermore, it seems that our ability to communicate using a common, reliable language has deteriorated. We are linguistically brutalized. Nowhere is this discordant trend more important than in our inability to talk about freedom in a meaningful and reliable way. The essential tenets of freedom, assuming that we can even establish a shared understanding of those essentials, are inseparable from the belief systems that we have come to call “the left” and “the right.” These are the polar ends of the aforementioned tug-of-war. But there is more at stake than the meaning of language alone. The failure of language runs in parallel with the failure of our political and economic system, and the price of failure is high. We are unable to make any headway in our disagreements when words like freedom can establish no common territory. The steady march toward democracy stumbles. We must therefore refresh our understanding, revitalize the definitions of words, especially words like freedom. While I will highlight the ideas of several prominent thinkers, the point is not to put them on a pedestal or a podium. The idea, rather, is to examine them as signposts, crystallized embodiments of the evolution of an idea embedded in our language.

While our discourse has faltered, many pundits have also claimed recently that democracy is declining in “the west.” There has been broad discussion of the sputtering of representative government, the reemergence of authoritarian systems and the increasing powers of a new class of oligarchs who live independently of government power. To be sure, these claims are broad brush observations, and governments change their tolerance for various freedoms over time. But there is clear evidence for concern. In the US, for example, freedom of the press has come under increasing pressures from both the government and the systematic machinery of our political economy. For example, the US has dropped to 45th in the world in the World Press Freedom Index (Reporters Without Borders). And it is trending downward. The relationship between a functioning language and a functioning democracy are nowhere more clear than in the freedom of the press.

What is perhaps most alarming is how the term “freedom” has become the banner for those who seem to want to cultivate power and corral it into fewer and fewer centers. Those with the most power espouse the need for more freedom, but what exactly does this mean? What we mean by “freedom” is not merely a demonstration of linguistic gymnastics. What freedom means, what it stands for in law and in the interpretation of law, determines how government governs, and how economies run. Perhaps it was a prescient forewarning rather than a than critique on his times when Orwell wrote that “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” More likely it was an observation that applies regardless of the current brand of dominant political philosophy. Power seems to prefer to gather rather than to disseminate.

I identify and examine three distinct domains of freedom: Personal Freedom, Economic Freedom and Hegemonic Freedom. These three domains are often in conflict with each other, and the domain that prevails will determine the kind of world we live in. How we define freedom will determine how we define ourselves, and how we live our lives.

- Personal Freedom: This domain is articulated clearly in 19th century political philosophers like Bentham and Mill who espouse the civic necessity for Personal Freedom. Another way to identify this form of freedom might be social or civil liberty, but even so it seems to require basic fundamental freedoms that reside in personhood. We remain enthralled by dreams of personal freedom. This definition refers to the liberty to think and say whatever we want, to be where we want, and as such it subjects our ideas to the scrutiny of the marketplace of ideas. Both Bentham and Mill offer a definition that is rooted in the belief that personal freedom is a political force and that the marketplace of ideas will drive the best ideas to the front. Personal Freedom forms the basis for a healthy democratic society.

- Economic Freedom: The second domain is articulated by 20th century economic philosophers like Hayek and Friedman, both of whom are reacting against the trend toward collectivist economic strategies that led to devastating world wars. While these two thinkers have emerged as idealized paragons of modern neoliberalism, their ideas about freedom deserve close attention. In this domain, free markets and competition create the only path toward an effective democratic order. Economic control through government is the enemy. Economic Freedom is formally anti-collectivist in its posture and its rhetoric, and economists like Hayek and Friedman argue for a political and economic system where freedom of production rules the day. It provides, in fact, the only viable road to true freedom.

- Hegemonic Freedom: The third and most recent domain of freedom stems from the rise of the globally super rich. Hegemonic Freedom is inextricably derived from the domains of Personal and Economic Freedom, and yet it represents a fundamental departure from them both. This new brand of freedom is realized through personal economic power and it proposes to subvert the democratic process, to push the ideas of Economic Freedom to an extreme where a small group of the super-rich operate “freely” outside of the constraints of government. This brand of freedom culminates beyond of the constraints of government, and it simultaneously assimilates and perverts the original ideas of Personal and Economic Freedom. Bastions of Hegemonic Freedom pursue ways to control government as the means to protect their wealth and power, and to prevent governments from reining them in and taking their wealth.

The word freedom holds mystical power and Merlin is always nearby when it is spoken.

We must also contend with wizardry. The word freedom holds mystical power and Merlin is always nearby when it is spoken. The most ambitious among us wield it like a magic sword pulled from the stone. But the idea of freedom controls us more than we control it. The history of civilization has brought us to this relationship with it. In many ways, the evolution of human political systems revolves around the competing spectra of freedoms. The gravity of liberty is inescapable and it holds us in its orbit. Liberty seems encoded somehow into our desires and dreams. Perhaps it is because we are so deeply social, so fundamentally dependent on one another for survival, that we paradoxically long for some kind of reversal. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. We cannot separate the idea of civilized society, or any form of society for that matter, from the idea of freedom.

The word freedom (or liberty) is so deeply ingrained in our psyche, in our collective spirit, that we easily fall prey to the manipulation of the idea. Someone on a podium will sermonize on the sanctity of liberty and our pulse rate picks up. These manipulations are not hidden far beneath the surface. They are easy to spot when we look. When a powerful speaker invokes the term freedom, we are often spellbound and we associate our most inarticulate hopes to what that might mean. And when we’ve already aligned our personal ideology with that speaker, when we wear the same jersey or carry the same flag, we forget to question what we are being sold and at what price we are buying. The idea of liberty can work on us like a magic spell. We must, therefore, become more skeptical, more scientific, when we hear the word freedom spoken from a podium.

We need look no further than the Old Testament to see the seeds of a dream. In Exodus God sends Moses to free the Israelites from the Pharaoh and then lead them to freedom. “Then Moses raised his hand over the sea, and the Lord opened up a path through the water with a strong east wind. The wind blew all that night, turning the seabed into dry land” (14.21). This is the very soul of deliverance. And in 19th century America, Harriet Tubman delivers slaves to the north on the underground railroad. The pursuit of freedom for African Americans continues today. The idea of contemporary freedom cannot be separated from the ancient dreams of personal freedom – the freedom to control your own body in an unfolding history where people were legally owned as property, where people were chained and bought and sold at the open market beside the nearest sea port. To have freedom is to have the most essential power, such as the power to move and to think and to speak in the world. The power to say no.

Of course freedom comes at a cost. In the views of Sartre, for example, we are all doomed to our freedom. “We are left alone, without excuse. This is what I mean when I say that man is condemned to be free.” If we are free, truly free, we must own our lives, our choices, our destinies. Sartre’s notion of freedom forces us to reflect, to look inward at ourselves and our lives and see them as a series of choices, choices that we must own. But this is not the kind of freedom that is on display in our time. Today, the idea of Freedom thrashes about between the three domains I outlined above: Personal Freedom, Economic Freedom and Hegemonic Freedom. These are the freedoms that battle for preeminence in our time.

II. Personal Freedom

The first domain, Personal Freedom, is perhaps most clearly articulated when it is considered as a form of civil participation. The ideas encompassed with the name of “freedom of the press,” for example, are the most overtly and politically engaged forms of Personal Freedom. This is precisely why freedom of the press is historically called the Fourth Estate (wikipedia). In this domain, Liberty is not merely a concept we can appreciate from our chaise lounge. It is an act we can make as a member of the broader community. And so we consider liberty as a formal component of civil participation, and we understand fully that liberty is a form of power.

This power performs many functions, not the least of which is to place a check on the rise of unbridled political power. Bentham considers how liberty of thought can pose a danger to the established order, and he writes that “in all Liberty there is more or less of danger: and so there is in all power. The question is – in which there is most danger – in power that is limited by this check, or in power without this check to limit it” (To the Spanish People, Letter 1). Bentham is quite clear on this point: unchecked power is the greater danger to the function of government. We must exercise the ability to express our ideas fearlessly in the public sphere. After all, “secresy [sic] in subjects, supposes tyranny in rulers” (Letter 1).

Another critical form of Personal Freedom in the civic arena has been named by history as the “freedom of assembly.” In this case the material end or purpose of the freedom to gather and assemble stems from the need to discuss the state of government and the condition of the governed. The purpose, in other words, of such a Personal Freedom is to openly discuss ideas about the quality of political leadership. Freedom of assembly can be viewed then as a bookend to the freedom of the press; it allows people to caucus so that they can debate, discuss, reason and organize around civic actions as they relate to the manifestations of power. Bentham continues in his letter #1: “In regard to assemblies in particular, insert a declaration, giving the people the assurance that, for as much as there exists not any law to the contrary, they remain at liberty, at all times, and in all places from which they are not excluded by special ownership, to meet, for the purpose of delivering their opinions, in the freest manner, on the conduct of their rulers.” With a brief nod to concerns over private property, Bentham is crystal clear that the right to assemble must exist so that the people may speak freely on the conduct and character of those in power. Bentham is keenly interested in how these ideas are reflected in the applications of law and not merely as cultural heuristics.

These ideas of Personal Freedom are of course embedded in the US constitution in the first amendment. They are primordial to the mythology of the United States. We naturally place them on a pedestal and hold them up as trophies of the national character. And yet even though the first amendment stands out as a fine example of unambiguous language, we still interpret it as if through a prism. There are other competing values that interfere with these ideals.

Bentham proposes stark concerns when civic personal freedoms are rolled back. In short, the ruling class will join with the wealthy and quickly consolidate an array of alliances that undermine the common people. “And thus, in the union of the monarchical and the aristocratical interest, you would see and feel, as here, an alliance defensive and offensive against the interest of the people” (Letter #1). We should keep this concern in mind when we discuss Economic Freedom in subsequent sections. And what does Bentham fear the most? It is not the ruler of the government. Rather, it is the persistent power that resides in the hands of the wealthy. “No: it is not so much of a monarch that I am afraid, for he is mutable. It is of the aristocracy that I am so much afraid; for that is immutable. It is itself immutable: and no less immtuably adverse is its interest to the interest of the people.” In other words, he does not fear so much the person who sits atop the throne, but instead it is the people who cannot be seen who are behind the throne.

Personal Freedom, when seen through Bentham’s lens, is essential to the power that must reside in the people, which is the power to choose their rulers. Personal Freedom, the freedom of the press and the freedom of assembly, are the essential empowerments that effectively place the ruler in the service of the people. In Letter #2, where Bentam addresses Spanish restrictions over the right to assemble, he explains how these powers, when removed, are the hallmarks of despotism. “Behold, then, the distinction between a government that is despotic, and one that is not so. In an undespotic government, some eventual faculty of effectual resistance, and consequent change in government, is purposely left, or rather given, to the people.” The removal of Personal Freedom is precisely the road to despotism. In this light, Personal Freedom embodies the power of the people over the power of the ruler. Personal Freedom provides the necessary check over the despot. It not only reflects that power, but it effectuates the power by its very operations in the civic arena.

When seen in this light, Personal Freedom is not merely a right, but rather it is a vital source of power, a force. It is the single most important force that holds the powers of the ruling class and the aristocracy (wealthy) class in check. And so when Personal Freedoms, the freedom of the press and the freedom of assembly, are under attack, it is a direct attack on that political force, the essence of any notions of democracy.

What I am interested in here is the evolution of the idea of freedom.

I have not said much here that is new or revolutionary, or even insightful. What I am interested in here is the evolution of the idea of freedom. The effort spent to explore how political force is rooted in personal freedom, rather, establishes a baseline of sorts. It places the idea known as Personal Freedom at near mythical status. This baseline definition of Personal Freedom then establishes both a civic and a psychic foundation. It is clearly civic, as Bentham details, but it becomes psychic in that we hold these notions highly in our values. These cultural values become inseparable from personal values for complex reasons that I will not go into here, except to propose that our relationship with freedom is so essential to our nature that we struggle to separate the personal from the civic. And it is precisely this foundation that makes us vulnerable to extrapolations of freedom into other arenas, arenas where we can quickly get into trouble.

In Letter 3, Bentham begins to break down the specific political malformations of the idea of freedom, the language of freedom. He points out that any discussion of freedom, ipso facto, must be further broken down into greater detail, greater specificity, so as to avoid a gross misuse of the very idea of freedom. Freedom alone, in other words, is the highest taxonomy of concepts and can be seen as a genus of other species and subspecies of ideas. To confuse different and unique manifestations of freedom (liberty) under an illusory umbrella definition of freedom represents nothing less than a misuse of power. And so “to putting aside nonsense, and determined to have sense to argue with if possible, I put aside Individual Liberty, and return to the word power: political power” (Letter 3). While our current civil systems continue to confront, discuss and examine many other “subspecies” of Personal Freedom, such as a sexual orientation, religious belief and “choice,” this paper highlights Personal Freedom as a non-violent political force, a form of representative power that resides within the governed.

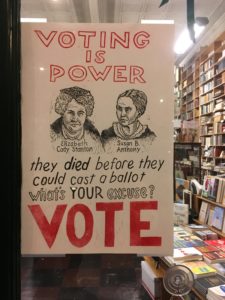

Published in 1859, Mill’s On Liberty appears at a moment when human slavery still legally drives the economics of the agrarian US, and Women’s rights have barely even begun to emerge as a factor in the discussion. The American Civil War is two years away from erupting and leading to the deaths of nearly one million Americans. And American Women are exactly 60 years away from having the right to vote in their own political system. The ideal of Personal Freedom for humanity, as advocated by Mill, remained in violent conflict with the very definition of humanity and who was counted as fully human.

J. S. Mill knew Jeremy Bentham, both as a teacher and as a leader. The continuity from Bentham to Mill is explicit and clear. There is perhaps no greater synthesis of the western ideas of freedom than Mill’s On Liberty. When we look at Mill’s iconic treatise, we find that he opens the piece with a discussion of power. It is as if he picks up the pen where Bentham put his down. Remarkably, however, Mill starts out by stipulating what he is not talking about. Mill seems apprehensive about the misapprehensions and misapplications of the term Liberty. He knows that Liberty is an elusive domain, and so he clarifies explicitly that he is not talking about free will. He is examining “civil, or social liberty: the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual” (p. 151). As the piece develops, Mill will work his way deeper into the subtleties of Personal Freedom, but the table stakes are unmistakable. “A time, however, came, in the progress of human affairs, when men ceased to think it a necessity of nature that their governors should be an independent power opposed in interest to themselves” (p. 152). Mill’s idea of liberty is inseparable from the direct exercise of power. But it’s not simply an issue of individual tyrants who need restraint. One of the most influential spokesmen for Personal Freedom, Mill goes further to address another form of abusive power, the tyranny of the majority: “…there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling.”

Mill then steps back and reframes his essay on a more generalized approach for an understanding of Personal Freedom. He defines three categories of freedom and formally designates them as “the appropriate region of human liberty.” These three realms are: freedom of thought, freedom of taste, and freedom of assembly, or what he calls the “freedom to unite for any purpose.” The ideas of Bentham are not far away. These three categories, though each having their own nuances (or subspecies), form the grand backdrop for Mill. And then he launches into the first of the three, “Liberty of Thought, from which it is impossible to separate the cognate liberty of speaking and of writing” (p. 160).

Personal Freedom, as it turns out, is a precondition. We soon discover that what Mill’s ultimate aim is “truth” and the only reliable process of finding it. [CE2] We are back to the classical beginning of philosophy itself. Truth, moreover, can only be achieved through the liberty of thought. He sees liberty of thought as the singular reliable weapon against the “propagation of error.” Repeatedly Mill attacks the tendency of individuals toward “error,” he attacks the “fallacious,” and he is on the lookout for “mistakes.” And while liberty of thought creates the path towards some kind of reliable truth, it also establishes the justification of judgement and action. “The steady habit of correcting and completing his own opinion by collating it with those of others, so far from causing doubt and hesitation on carrying it into practice is the only stable foundation in a just reliance on it” (p. 166). Mill’s grand conception of truth is in fact a deeply practical one, for it rests not only on the process of debate and proof, but such a rigorous process then forms a direct line to earned authority and justified action. In fact, “on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right” (p. 165)

Mill, like Bentham, adopts a utilitarian stance in his idea of Freedom. He is not an idealist fighting for the cause of grand Truths. The pursuit of truth, rather, through “liberty of thought” represents a combative arena where contestants battle for their position, and “it is on the calmer and more disinterested bystander, that the collision of opinions works its salutary effect” (p. 190). Furthermore, Mill adopts the nuanced position of rejecting binary truth (wherein one point of view is either right or wrong). Mill furthermore rejects the worldview in which revolutions of thought require the victory of one opinion and the defeat of another. More often, “conflicting doctrines, instead of being one true and the other false, share the truth between them, and the nonconforming opinion is needed to supply the remainder of the truth of which the received doctrine embodies only a part” (p. 185). Received opinion, then, becomes the enemy of truth. Dogma stands in opposition to any vital truth. Mill, like Bentham, advocates for the vitality of free public discussion. Personal Freedom, therefore, becomes the path to civil society, a society that freely pursues vital truths and thus innoculates itself from the tyranny of dogma and authoritarian rule.

III. Economic Freedom

That is enough, for now, on the domain of Personal Freedom, at least as it has been defined by the Englishmen, Bentham and Mill. When looked at categorically, Personal Freedom represents the foundational root of the other domains of freedom that will be discussed next: Economic Freedom and Hegemonic Freedom. The meaning of Personal Freedom evolves violently in the US between the Declaration of Independence and the Civil War, and by the time of the World Wars of the 20th century, the ideological boundaries of Personal Freedom become disrupted in profound ways and with profound implications.

As we transition now to Economic Freedom, I will focus on Hayek and Friedman as the central spokesmen. There are many other spokesmen for Economic Freedom that could be chosen, but these two stand out as flag bearers in the crowd and deserve close examination. With both Hayek and Friedman, we quickly discover that human liberty has grafted on an entirely different branch of ideas and implications. In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek offers a stark warning to world leaders in the second half of the 20th Century, a warning about a path to economic slavery and the totalitarian state. We have chosen the wrong road, the road of collectivism. The title itself serves as a cautionary flare, for Hayek articulates the case in which economic models that rely on government control rather than individual liberty lead to disaster, to economic and personal “serfdom.” In his 1956 Preface (12 years after the original publication), Hayak reaffirms his premise that “only if we understand why and how certain kinds of economic controls tend to paralyze the driving forces of a free society, and which kinds of measures are particularly dangerous in this respect, can we hope that social experimentation will not lead us into situations that we do not want” (p. 45).

In Hayek’s original Introduction to the 1944 text, he references none other than Mill as he sets up the structure of his socioeconomic argument. Mill, Hayek points out, “drew his inspiration, more than any other men, from two Germans” (p. 61). It is vital to note here that Hayek’s motivation stems unequivocally from the rise of National Socialism in Germany. National socialism led directly to Nazism, totalitarianism, and catastrophe. But Hayek’s argument here is not that Germans are inherently predisposed to fascism. Freedom does not reside natively within certain peoples. Rather, when a nation’s economic system abandons free markets (i.e. economic liberty) in favor of national planning, we are indeed then on “The Road to Serfdom.” It is the idea, not the people, that is the real enemy. “Mere hatred of everything German instead of the particular ideas is, moreover, very dangerous, because it blinds those who indulge in it against a real threat” (p. 61).

Hayek looks out at the world of 1944 with an economist’s perspective and sees the ravages throughout Europe and the world. Hayek writes from the shadows of destruction and devastation brought on by the Third Reich and its allies. He sees economic policy as inseparable from these global disasters. It is, in fact, the causal relationship. After highlighting Germany, Italy, Japan and Russia as case studies in centralized economic control, Hayek then makes his essential argument and states his warning: “…the contention of this book that the political development had something to do with their economic policies was then still indignantly rejected by the advocates of planning in [England]” (p. 43). In other words, national leaders were blind to the impact of economic models that relied on collectivist planning models, and they failed to understand the levers of power in their own nation-states.

According to Hayek, Economic Freedom and Personal Freedom are convergent, if not coterminous, and the course of history in the first half of the 20th century reveals a steady movement away from “liberal” philosophies: “We have progressively abandoned that freedom in economic affairs without which personal and political freedom has never existed in the past” (p. 67). This is the essential conjoining of Economic Freedom to Personal Freedom upon which so much depends. The two cannot be separated. And the evil that Hayek speaks of has a name, and that name is National Socialism. In short, “socialism means slavery” (p. 67). The question that arises, of course, is whether the personal freedoms discussed previously (freedom of thought, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly) are fundamentally equivalent to the freedoms of a market-based economic model and economic production. In other words, the question becomes this: is the freedom to economically produce what we need or want an equivalent and necessary aspect of personal freedom? Hayek answers in the affirmative. As it turns out, he will end up speaking for many others who advocate for laissez faire economics.

This brand of Economic Freedom does not apply only to the mundane workings of shop-keeping and dairy farming. Hayek argues that individualism and risk-taking have unleashed scientific revolutions. “Only since industrial freedom opened the path to the free use of new knowledge, only since everything could be tried – if somebody could be found to back it at his own risk – and, it should be added, as often as not from outside the authorities officially entrusted with the cultivation of learning, has science made the great strides which in the last hundred and fifty years have changed the face of the world” (p.70). Human freedom changes everything. When looked at in this light, from Hayek’s rhetorical vantage point, and considering (merely as familiar examples) the changes brought about by the ideas of Newton, Darwin, Einstein, and the Wright brothers, we could argue that the unleashing of human freedom is the true innovation, the essential alteration in the structure of civilization that begets even more alteration, more change than could possibly have been imagined in a world where an individual’s liberty was limited by fealty to one’s feudal Lord and his Priest. Once the creative force of Personal Freedom has been fully and finally released from the bottle, we sparked the advancements in human understanding of the world. And not just understanding, but also engagement and alteration. As Hayek views “industrial freedom,” it did not merely give us the ability to understand flight. It allowed us to fly.

In The Road, Hayek observes how the socialist’s use of “freedom” shifts rhetorically as a means to reframe the development of civilization. He too sees the meaning of this word as a key battleground. As the conceptual foundations of socialism fell into place, the tug-of-war over the meaning of freedom was well under way. Emergent socialists, as Hayek sees it, made the case that individuals could only achieve freedom through coercively planned frameworks for economic activity. “The change in meaning to which the word ‘freedom’ was subjected in order that this argument should sound plausible is important. To the great apostles of political freedom the word had meant freedom from coercion, freedom from the arbitrary power of other men… The new freedom promised, however, was to be freedom from necessity, release from the compulsion of circumstances which inevitably limit the range of choice for all of us, although for some very much more than for others. Before man could be truly free, the ‘despotism of physical want’ had to be broken, the ‘restraints of the economic system’ relaxed.” (p. 71). We can see Hayek articulate how the freedom as outlined by the likes of Bentham and Mill (and others), was repositioned by emerging socialists as merely transitional. Freedom from economic need was the next step for collectivism. But Hayek counters these attempts to appropriate the definition of freedom. “There can be no doubt that the promise of greater freedom had become one of the most effective weapons of socialist propaganda” (p. 72).

In order to understand Hayek’s nuances more fully, it is important to know that he does not advocate a laissez faire system, and he explicitly advocates for action on the part of the state. “Of course, every state must act and every action of the state interferes with something or other” (p. 118). But this action should be based in law that transcends the individuals in power at any given moment in time. He believes that the state must protect those who lack power or standing as well as guard against the dangerous and polluting consequences of production. But competition unshakably reigns at the heart of his position. “To prohibit the use of certain poisonous substances or require special precaution in their use, to limit working hours or to require certain sanitary arrangements, is fully compatible with the preservation of competition” (p. 86). Even though Hayek acknowledges and accepts the regulatory role of government, we must still recognize that Hayek’s articulation of Economic Freedom represents a departure from Personal Freedom. Economic Freedom leads directly to the freedom of production. When we produce things that come into the world, we alter the landscape for everyone. In some cases, we produce “poisonous substances” and we tend to abuse labor. The physical and environmental impact alone presents Economic Freedom with complex entanglements that do not apply to Personal Freedom.

Philosophers stipulate etymologies. They define their terms, and they decide what gets included in the definition and what gets excluded. This definitional process frames the underpinning of their arguments. Their terms are usually conceptual, like the term freedom. And they will often propose a new definition, new ideas to be included and some older ones excluded. They are on guard against “received ideas,” which provides a reliable technique for injecting “new ideas.” What we are talking about here is the unfolding definition, the unpacking and the repacking, of the contents of freedom. We can see that Mill and Bentham outline a case for Personal Freedom that necessarily includes free expression, free press, and free assembly as forms of non-violent political power that can help to keep the manifestations of tyranny in check. We can also see how Hayek wishes to reestablish free production as utterly necessary to avoid the authoritarian inevitabilities of collectivist economic systems. If Personal Freedom is the ultimate goal, what humans want as the end result (Hayek concedes that even most Socialists want that end result), we cannot get there without Economic Freedom. Whether you call it collectivism, socialism, or centralized planning, the road is the same: the loss of Personal Freedom and the decline of civilization. The world-wide disasters of the 20th century provide Hayek with ample demonstration that, in his eyes, Adam Smith was right all along.

It might come as little surprise that Hayek ventures into the same epistemological territory as Mill. Truth and truthfulness come under scrutiny. As Hayek sees it, the collectivist economic model leads inexorably toward the totalitarian state. And one of the necessary victims of that model is truth. This outcome has an inevitability in it for Hayek, and what follows necessarily is the need for everyone to fall in line. “The most effective way of making everyone serve the single system of ends towards which the social plan is directed is to make everybody believe in those ends” (p. 171). The totalitarian system, for example, requires the extinction of dissent. With the elimination of the marketplace, we also eliminate the marketplace of ideas. The truth then becomes a part of the planning process, a carefully crafted construction designed to create hierarchical obedience. “There is consequently no field where the systematic control of information will not be practiced, and uniformity of views not enforced” (p. 176).

In Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman picks up where Hayek leaves off, and he carries the Economic Freedom argument to an even purer expression of laissez faire values. Friedman openly acknowledges the influence of Hayek on his own thinking. The two economists knew each other well and explicitly referenced one another’s works. In the 2002 introduction, Friedman references Hayek’s Road to Serfdom as “brilliant” (p. viii) and in Chapter 1 as a “penetrating analysis” (p. 11). But Friedman presses the argument forward and wastes no time staking out his position in plain language: “To the free man, the country is the collection of individuals who compose it, not something over and above them” (p. 1). One’s country, in this formulation, should represent nothing other than a container of individuals. A free nation’s character becomes simply the bottoms up collection of the totality of the individuals. To me it is striking here that Friedman uses the word “country” and not the word “government,” for while government is a construction of man for the sake of the state, the country certainly represents more than human-centric governance. The country includes the land, the resources, the geography, the place itself.

Friedman’s free-wheeling rhetoric represents a departure from Hayek’s more analytical style in important ways, and there are times when his proposals fall far short of intellectual rigor. Friedman takes the important step, for example, of conjoining economic freedom and personal freedom, as well as all other forms of freedom, in what he defines as “freedom broadly.” For Friedman, “freedom in economic arrangements is itself a component of freedom broadly understood, so economic freedom is an end unto itself” (p. 8). What does this mean exactly? If Economic Freedom is a member idea of the set of ideas known as “freedom broadly,” and since freedom broadly understood is clearly what we value most, then Economic Freedom must follow as a logical inevitability. This argument, while at first glance appearing to be conceptually and logically sound, reveals a formative bias. But with only a modest amount of scrutiny, we can see that Friedman conflates Economic Freedom with all other forms of freedom and performs the neat trick of saying that this justifies Economic Freedom as an ultimate end. It’s a bit like saying “radiation is a natural occurrence in the world,” and thus “radiation from a nuclear reactor disaster is a natural occurrence in the world.”

While these two thinkers have emerged as idealized paragons of modern neoliberalism, their ideas about freedom deserve close attention.

This is not the only logical fallacy that Friedman commits in the early chapters of Capitalism and Freedom. “Fundamentally, there are only two ways of coordinating the economic activities of millions. One is central direction involving the use of coercion – the technique of the army and the modern totalitarian state. The other is voluntary cooperation of individuals – the technique of the marketplace” (p. 13). This is an exemplary use of the false dichotomy, were Friedman constructs what appears to be a comparison of equals, but which in fact is a hierarchy where one is preferred over the other. This might even represent an unalloyed, textbook example of the false dichotomy. In this case, the coercive model is the collectivist model and it is anti-freedom. Whereas the marketplace model is the model based on freedom and it is clearly the most desirable means and end. QED.

These fallacies are important because they point to the “all in” ideology that Friedman postulates and advocates. He does not offer a balanced, scientific depiction of the problems and the arguments, which would certainly include identifying the dangers of the marketplace model for society. Perhaps more importantly, these fallacies require our attention because Friedman was not merely an economist writing obscure papers that were bound and shelved and read by a few scholars from time to time. Friedman personally advised both Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan on how best to direct the economies of the UK and the US. Hayak championed and translated these laissez faire economic policy principles, and they were actively pursued in the 1980’s by the governments of the United Kingdom and the United States.

And now we can return to Friedman’s odd usage of the word “clearly,” because it appears repeatedly and rapidly in clusters throughout the early parts of the Capitalism and Freedom. Here are just a few examples. “Clearly, economic freedom, in and of itself, is an extremely important part of total freedom.” What exactly is “total freedom,” and what are we to make of the use of this word, clearly? To say that something is “clearly” this, or “clearly” that, does not make it so. In fact, it reads as if the author has dropped all pretense of rigorous analysis. Objectivity has been abandoned for polemics. Just a few sentences below this, we find that “political freedom in this instance clearly came along with the free market” and this word continues to crop up in the following paragraphs as if to prop up some kind of assumed truth. Friedman appears to be selling (rather than investigating) these ideas.

In the fine debating tradition of “either you’re with us or you’re against us,” we also learn that if you aren’t in agreement with the need for economic freedom, then you are some kind of fascist. “Underlying most arguments against the free market is a lack of belief in freedom itself” (p. 15). The word “belief” here provides a good reason to pause. In the realm of economics, it would seem that “belief” is not the standard toward which we want to aspire. It would seem, rather, that evidence and objective examination of cause-and-effect would be the responsible way to go.

When we move into the topic of “neighborhood effects” we catch brief glimpses into how far his radical ideas of economic freedom will go. After Friedman has spent some time and ink sketching out the role of government to create the “rules of the game” he then weighs into several of the challenges of free market economics. He dispenses with monopolies quickly and then broaches the topic of how we might impact others with our freedom to produce. “The obvious example is the pollution of a stream. The man who pollutes a stream is in effect forcing others to exchange good water for bad. These others might be willing to make the exchange at prices. But it is not feasible for them, acting individually, to avoid the exchange or to enforce appropriate compensation” (p.30). Friedman’s treatment of this scenario reflects a staggering blindness to the impact of man on the rest of the world. The idea that others might be willing to exchange bad water for a price reduces the impacts of human pollution merely to the human-centered world of commerce. It is as if Friedman cannot see through the clear stream water to what else lives there, for the stream may only be valuable to another man, or to a company.

Anthropocentrism can also be defined as “human supremacy” or “human exceptionalism.” In this worldview, an event like poisoning a stream can be handled simply through the exchange of money. And so we see how a anthropocentric free market philosophy can create serious problems, not only for other free individuals but for every other living being. And spending 57 words on neighborhood effects, Friedman is done with the polluted stream. Economic freedom in Friedman’s world seems to include the near total disregard for the well-being of all forms of life that are not human, except that they might be tallied into a total cost to the polluter.

Friedman spends more energy on the national parks system and concludes that parks could, and perhaps should, be handled by free enterprise. “I cannot myself conjure up any neighborhood effects or important monopoly effects that would justify government activity in this area.” Once again, Friedman’s copious imagination seems depleted of insights beyond his own biases. What about, for example, the regulation of endangered species, especially those that don’t recognize the borders of a national park, that have been threatened by the freedom of individuals to hunt and kill them? How should this be managed by private enterprise? Whether or not you agree with this “neighborhood effect,” it wasn’t hard to “conjure up.”

Friedman’s zealotry for economic freedom extends, it appears, into the mother’s womb. “The freedom of individuals to use their economic resources as they want includes the freedom to use them to have children – to buy, as it were, the services of children as a particular form of consumption” (p. 33). Now, in all fairness, if one were to take a purely economic point of view of the world, then this argument can seem to flow from a defensible philosophy rooted in enthusiastic free market thinking. But, of course, there are competing economic points of view that would also stake claims on the value of children as, say, sources of future labor. But we must pause here to observe that such zealous economic views relegate the human impacts on the rest of the living world as either “neighborhood effects” or areas of excessive regulation. Friedman’s philosophy of freedom reveals a radically nearsighted vision for liberal economic theory. Moreover, he seems blind to its impact on a world where life has evolved over billions of years.

There are many other free market economists that could be surfaced and examined, but Hayek and Friedman are clearly two of the most prominent torch bearers of these ideas. While they departed from each other in important ways, they both were strong and impactful champions of the ideals of Economic Freedom. And one can see clearly now that they were wildly successful, perhaps even more successful than they could have imagined. We have steadily and successfully grafted the branch of ideas known as Economic Freedom onto the root of the idea known as Personal Freedom, and we don’t seem to know how handle what it is that we have created. And what have we created exactly? I call it Hegemonic Freedom and Nancy MacClean calls it “the radical rich minority.” And so when we think today about the battle over freedom, and about minority rights, we are no longer thinking about the right minority.

IV. Hegemonic Freedom

In Being and Nothingness, Sartre considers freedom as essential and inescapable. We are all, as he views it, condemned to be free. But there is a formidable spark of insight in his contemplation of freedom that raises up to meet the idea of Hegemonic Freedom. “I apprehend it, or at least I try to apprehend it as the original beginning of my possible, and I do not admit at all that it has in itself a beginning. I assert then that an act is free when it exactly reflects my essence. However this freedom which would disturb me if it were freedom before myself, I attempt to bring back to the heart of my essence-i.e., of myself. It is a matter of envisaging the self as a little God which inhabits me and which possesses my freedom as a metaphysical virtue” (p.42). What else to replace God but the idea of the self as a god? Otherwise, what are we to do with gods other than to relegate them to the garbage heap of history? While there is risk of pulling Sartre out of his ontological context, the idea that freedom emerges within the individual as a godlike entity bears close to the concept of Hegemonic Freedom. My observation is simply this: We have entered an era in which Personal Freedom and Economic Freedom have birthed a new domain of freedom, and this freedom is one that seeks to establish a degree of individual power that aspires to have untouchable powers. We are no longer talking about Personal Freedom – we are talking about personal power. We have entered the era of Hegemonic Freedom.

Hegemonic Freedom observes that there are individuals that can now achieve a level of Economic and Personal Freedom that swells and extends their power beyond the reach of the traditional state authority.

Hegemonic Freedom, as I will argue here, observes that there are individuals (and organizations of select individuals) that can now achieve a level of Economic and Personal Freedom that swells and extends their power beyond the reach of the traditional state authority. The government is no longer the source of power to be feared. The situation has reversed. The government is now the check against Hegemonic Freedom, and government’s ability to perform that function continues to come under assault. The idea of Personal Freedom, which was once an idea that was intended to allow individuals to overcome the abuses of totalitarian governments, has become the means to abuse the people that those governments are supposed to represent. The proverbial tail is now vigorously wagging the dog.

Individuals (and organizations) that pursue this form of freedom, a freedom whose essence is deeply rooted in individualistic manifestations of power, view governments as obstacles to the ultimate reach of extranational authority. Hegemonic Freedom therefore siphons concepts from the ideas of Economic Freedom in such a way that Personal Freedom for select individuals (and organizations) reaches new orbits fuelled by levels of extreme wealth, a wealth that comes through the winnings made possible by the values of Economic Freedom. Hegemonic Freedom represents the ruthless offspring of Personal Freedom and Economic Freedom. It does not come into existence without both parents. When acting at its most influential, and perhaps its most cynical, Hegemonic Freedom appeals directly to the enlightenment rhetoric of Personal Freedom. In other words, the value system of Economic Freedom creates the possibility for Hegemonic Freedom and in so doing the rhetoric of Personal Freedom remains rooted deep into the ground upon which Hegemonic Freedom grows. These roots in Personal Freedom provide an endless supply of rhetorical material for its surrogates and surreptitious spokemen. You cannot chop down tree of Hegemonic Freedom without pulling out the roots of Personal Freedom. It is a fantastic conundrum, and one that we must learn to free ourselves from.

When considered as a source of raw political force, the representatives of Hegemonic Freedom marshal their considerable resources in order to buy and sell their way to the podium. While they are not always successful, they continue to craft their messages based in the enlightenment language of Personal Freedom. But it is a ruse, and a very effective one. They orchestrate messages of freedom that are then broadcast into the market by the media by consolidating and controlling the narrative and the storyline. They fund the political campaigns of those that will espouse the values of Economic Freedom regardless of evidence of its abuses. The forces that represent Hegemonic Freedom directly fund and influence the theories and ideologies taught at major universities by making foundational donations to the departments where such ideas are taught.

The architects of these radical ideas state explicitly that the outcomes of a laissez faire-leaning system, an expressly individualistic system, do not matter. All that matters is the adherence to the first principles of anarchic individualism. Buchanan claims unapologetically “that is ‘good’ which ‘tends to emerge’ from the free choices of the individuals who are involved” (Limits of Liberty, p. 9). His line-of-argument on this point is notable. The first principle of individualistic conduct replaces the scientific notion of evidence. Furthermore, the idea of the social contract is superfluous. “It is impossible for an external observer to lay down criteria for ‘goodness’ independent of the process through which the results are obtained” (L.o.L., p, 9). He says that whatever emerges from a totally free system is “good” by the very nature that the system was free. But then Buchanan immediately argues that outcomes cannot be seen as independent from process. Does this mean that both outcomes and process matter? Apparently not, because then he immediately reiterates that the outcomes are irrelevant. “And to the extent that individuals are observed to be responding freely within the minimal required conditions of mutual tolerance, any outcome that emerges merits classification as ‘good,’ regardless of its precise descriptive content” (L.o.L., p.9). Is it that the outcomes don’t matter, or is it that the outcomes of a laissez faire system are well known? The rich and the powerful are “free” to marshal their resources to exploit the polity.

“It is a matter of envisaging the self as a little God,” says Sartre. A little God indeed. Perhaps it can be said that God is not dead after all, but has instead been born again within those individuals who choose to aspire to a Godlike freedom. The statistics are all well-known at this point. “What’s been going on the last 30 years? It’s a story of the uber-wealthy percent increasingly moored to markets and markets unmoored to any rules” (The Atlantic). When the markets are unmoored, we are living the values of Economic Freedom. “The rise of the rentiers is nothing new. What is new is the degree of financial globalization and liberalization that has supercharged the fortunes of the super-wealthy even beyond robber baron levels.” Liberalization means Economic Liberty, the freedom to operate in an unregulated system.

And thus we now live in the upside down world. The ambitious and talented individuals who once pursued freedom from the totalitarian state have now gained powers beyond the state, and they have simultaneously gained powers over those that remain within the governance of the state. These powers flow from extreme wealth, a wealth born of Economic Liberty. Of course, this power has not been distributed evenly. And for men like Buchanan, this is how it should be. “For my purposes, there is no need to discuss in detail the degree of possible inequality among separate persons in the conceptual state of nature that has been used to derive the logical origin of property rights. Those who have referred to the strong enslaving the weak may well have exaggerated the differences” (L.o.L., p. 34). That a functional state of free individuals begins with inequality is not only natural, but it requires no discussion.

The triumph of Economic Freedom has led us all to the rise of individuals who function independently of the traditional nation-state, those few who have the ability to operate independently of the reach of government power. This is in fact what makes the government their enemy, for it is only the government that can constrain their ascendency. Only a powerful government can seize the source of their power, which is their wealth and their property. And so it benefits the radical rich minority to argue for a constitutionally weak government.

In another familiar signal of our current upside down world, the term we use for an economic liberal is in fact a political conservative. In other words, the name we give to those who advocate and legislate for Economic Freedom is “Conservative.” To be a conservative in this upside down world is in fact to be a liberal. But here’s the brilliant logic of this: to espouse Economic Freedom allows the wealthy and the powerful to conserve their wealth and power through the mechanisms of unregulated markets. And yet we are flummoxed, walking around in a fog. The term liberal, of course, refers to economic liberalism, otherwise known as Economic Freedom. But these so-called conservatives believe in the values and policies of economic liberalism. We find ourselves confounded in our attempts to make sense of our situation.

It is one of the most effective linguistic reversals of our time (and perhaps the bellwether of the era of Hegemonic Freedom). And since this metaphorical bellwether is in fact the sheep that leads the flock, we must ask if we can see the teeth of the wolf. And what these self-named conservatives have mastered is the ability to turn liberalism into a term of weakness, a set of ideas that somehow threatens a citizen’s Personal Freedom. All of which brings us back to square one. We still yearn for the existential release of freedom. We want to be unbound, unchained, untethered, but once we have been released, it turns out that we want to have the powers of a little God.

The numbers of inequity are well known by now. We see them so frequently that we struggle to think critically about their implications. We become inured to the inevitable, or perhaps worse we each see these numbers as the scorecard in a game we are losing. Here’s one example: “the eight richest [individuals] have the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of the world — nearly 4 billion people” (Business Insider). We shrug our shoulders and go back to work.

The rise of highly wealthy individuals is not limited to the countries considered to be part of The West. We might look at China, or India, or Russia. The trend, in other words, is increasingly in the direction of extremely powerful individuals whose power reaches beyond the state. “The French economist Thomas Piketty estimates that more than half of Russians’ total wealth is held offshore in this manner – some $800bn (£597bn) – and by a tiny number of people, perhaps just a few hundred” (The Guardian). This is not Russian wealth but the wealth of certain Russian individuals. This wealth then finds its ways into other nations in order to avoid the constraints of any single nation. “Over the past decade, £68bn has flowed from Russia into Britain’s offshore satellites such as the British Virgin Islands, Cayman, Gibraltar, Jersey and Guernsey. That’s seven times more money than has flowed directly from Russia into the UK. (On top of that, some £94bn has poured out of Russia into Cyprus, £13bn into Switzerland, and £23bn into the Netherlands, which has its own network of tax havens.)” It is a staggering notion that 50% of the wealth of a country like Russia resides in other countries, and that this money is controlled by an increasingly small number of individuals and organizations.

We hear the phrase “no one is above the law” in public discourse when someone in a position of power has been accused of breaking the law. It is time-tested pabulum, but we like to think that it is true nevertheless. It sounds good to say it, but saying it doesn’t make it true. Usually said by a political opponent, the phrase begs the question of whether or not certain individuals are in fact above the law. To be able to operate “above the law” is to achieve Hegemonic Freedom, for it is only the government that can restrain or constrain the power of the extremely powerful and extremely wealthy individuals. If one lives “above the law” then they live “above the reach of government.” It is government that has the power to seize the assets and to punish individuals by taking away their basic freedoms, i.e. by putting them in prison for breaking laws. It is precisely this power of government that drives proponents of Economic Freedom to argue repeatedly that “the government is the problem.” The argument goes like this: government regulation, taxation and legislation damages the benefits of the unfettered free market, and thus destroy jobs (low paying jobs, to be clear). It operates like a veiled threat. This is the message platform that pours out from proponents of Economic Hegemony. “Less government equals more jobs for you.”

But the subversive vein is not always quite visible, and it is the vein through which the blood of Hegemonic Freedom runs. When government becomes the problem, we weaken our collective ability to ensure that “no one is above the law.” Thus, if we are indeed “a country of laws” then it is the government that will create and discharge those laws. We fail to grasp this truism when someone waves the flag of freedom in our faces. We may be a country of laws, but do they apply to everyone? There is a peculiar calculus at work here. It is precisely the captains of Hegemonic Freedom that espouse the values of weakened government, which in turn enables them to grow their power, to achieve greater Hegemonic Freedom, to become “like a small god.” Less taxation, less regulation and less legislation lead to greater accumulation of wealth and power for individuals and those that run large organizations. Meanwhile, those who run large organizations are achieving levels of income that set them apart from the citizenry. “In the 1950s, a typical CEO made 20 times the salary of his or her average worker. Last year, CEO pay at an S&P 500 Index firm soared to an average of 361 times more than the average rank-and-file worker, or pay of $13,940,000 a year, according to an AFL-CIO’s Executive Paywatch news release today” (Forbes, May 22, 2018). One might argue that stratospheric pay rates follow from a corresponding extreme level of talent and responsibility. It is well deserved, and the rising tide raises all boats. This all too familiar refrain tends to come from the true believers of Economic Freedom. To run a large organization, in other words, requires tremendous skills and entails great liabilities. But we need only examine the 2008 financial crisis to see that personal accountability does not follow from extreme levels of compensation. And neither does talent. Could it simply be the case that the current incarnation of Economic Freedom means that extreme wealth simply flows to the top by design? That it is systemic? And thus Hegemonic Freedom becomes an inevitability?

The damage done from the 2008 banking crisis is well documented. While the cause was born in the US financial markets, the effects were global. The people who paid the highest price were those at the bottom 90% of the economic ladder. Not only did they bear the brunt of the collapse, they paid the bill. But who was punished and who was held accountable? Were there people in power that were above the law? The individuals at the top of the financial institutions paid no such price. In fact, in many cases they were paid bonuses for their performance. This is not new information, but it is worth revisiting for a moment. “Since 2009, 49 financial institutions have paid various government entities and private plaintiffs nearly $190 billion in fines and settlements, according to an analysis by the investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. That may seem like a big number, but the money has come from shareholders, not individual bankers. (Settlements were levied on corporations, not specific employees, and paid out as corporate expenses—in some cases, tax-deductible ones.) In early 2014, just weeks after Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, settled out of court with the Justice Department, the bank’s board of directors gave him a 74 percent raise, bringing his salary to $20 million” (The Atlantic). But the point here is not to rehash a well understood demonstration of wealth and the power that accompanies that wealth. Nor is it an opportunity to further impugn the byzantine banking system. That has already been done. The point is to see this episode from the lens of Hegemonic Freedom. The leaders of global financial institutions are prime examples of the new royalty. They are the new princes, the new lords, the new bishops in an era where the values of Economic Freedom, while playing to the promise of Personal Freedom, have achieved the full benefits of Hegemonic Freedom. They are not only above the law, but they articulate the terms of the new laws. Joseph Stiglitz articulates the growing power gap using simple terms in Freefall, “In this new variant of the conflict between Wall Street and the rest of the country, the banks held a gun to the heads of the American people: ‘If you don’t give us more money, you will suffer’” (p. 50). But it should be pointed out that banks don’t do anything. The leaders and managers at the tops of those institutions determine the values and call the shots.

Nancy MacLean explores Buchanan’s body of work and his practical impact in the current situation and she highlights the dreamlike notion of freedom as an offering dangled before our eyes, and perhaps before his own eyes.

The dream of this movement, its leaders will tell you, is freedom. “I want a society where no one has power over the other,” Buchanan told an interviewer earlier in the century. I don’t want to control you and I don’t want to be controlled by you. It sounds so reasonable, fair and appealing. But the story told here will show that the last part of that statement is by far the most telling. This cause defines the “you” its members do not want to be controlled by as the majority of the American people. And its architects have never recognized economic power as a potential tool of domination. To them, unrestrained Capitalism is freedom. (Democracy in Chains, p. xxxiv)

The “movement” MacLean talks about here represents what I would call the people and the ideas that have created a world where representative governments find themselves battling with the forces of Hegemonic Freedom. It is the collection of Billionaires, and those who aspire to orchestrate that ultra-free world with them, who have the power to influence how we think. In 1956, there were no Billionaires (MacLean, p. xxiii). Now there are over 2,000 of them, representing almost eight trillion dollars in wealth. This math cannot be accounted for by inflation.

We become like sops when sprinkled with the rhetoric of freedom. We do not ask ourselves what lies at the bottom of this foggy notion of freedom. It feels good, and we believe that it somehow invokes our enlightened self-interests, but what is the true price of such freedom and who pays for it? We do not see the message behind the message. We do not combat the spells cast by the magical rhetoric of freedom and we do not ask the simple question, “What exactly do you mean by Freedom, sir? Please tell me who wins and who loses as we grant the powerful with more and more power all in the name of freedom.”

In closing, let’s assume for a moment that Hayek is right when he argues that the rise of Personal Freedom has led us to radical advancements in science, art, technology and man’s power to understand (and to change) the world. Furthermore, let’s argue that the diverse domains of human freedom have in fact unleashed the most creative (and destructive) forces on the planet. We might say then that nuclear bombs and genetic engineering are merely two of the more spectacular fruits of human creativity, made possible only by freeing humankind from the orthodoxy of churches and kings. It seems to me that there is ample evidence to support this claim, and I confess that I am convinced. Now what? Now we must ask the questions that Buchanan explicitly refuses to ask. We must ask about where this power takes us. And so the question becomes this: how will we harness the powers of human freedom? And to what ends?

References

- Liberty of the Press, and Public Discussion, Jeremy Bentham, Edited by John Bowring, 1843

- On Liberty, J. S. Mill

- The Road To Serfdom, F. A. Hayek

- Capitalism and Freedom, Milton Friedman

- The Limits of Liberty, Between Anarchy and Leviathan, James M. Buchanan

- Being and Nothingness, J. P. Sartre

Additional Background Material

- Freefall, Joseph Stiglitz

- Democracy in Chains, Nancy MacClean

- The Atlantic, “What Putin Really Wants”

- The Guardian, “Sergei Roldugin, the cellist who holds the key to tracing Putin’s hidden fortune”

- The Guardian, US ‘name-and-shame’ list of Russian oligarchs binned by top Trump official – expert

- The New Republic, Political Corruption and the Art of the Deal

- New Yorker, Putin, a Little Man Still Trying to Prove His Bigness

- New Yorker, A Theory of Trump Kompromat

- The Atlantic, The Plot Against America

- The Atlantic, Street’s Bankers Stayed Out of Jail

- Alex Stamos, How the U.S. Has Failed to Protect the 2018 Election–and Four Ways to Protect 2020

Teaching us a drum-song phrase by phrase, the sensei seems to intuit just how much novelty we beginners can absorb. She gradually introduces nuances of technique, gently correcting our form when necessary. She challenges us without loading on too many new ideas at a time. She says, “If this is too much to think about right now, then don’t worry about it.”

Teaching us a drum-song phrase by phrase, the sensei seems to intuit just how much novelty we beginners can absorb. She gradually introduces nuances of technique, gently correcting our form when necessary. She challenges us without loading on too many new ideas at a time. She says, “If this is too much to think about right now, then don’t worry about it.”