Helping Mom Communicate after the Dead Started Visiting

After a series of infarcts, Mom came to believe that her dead sister Madeleine and their dead father Frank were coming to visit; had already come and gone; or had disappointed her again by failing to show up.

Mom’s delusions drove Dad crazy. “You father never did anything decent while he was alive. Why do you think he’ll do anything now?”

The last time we were all together, I took Mom aside and asked, “Are Frank and Madeleine still paying you visits?”

Mom lowered her voice and said, “They really come all the time. I can hardly get them to leave, Madeleine talks so damned much. But we can’t let Dad know. He can’t handle it.”

When Dad died, I inherited Mom. Frank and Madeleine came along for the ride.

The unit manager at the assisted living facility was hesitant to admit Mom. He feared mom’s delusions might place herself and others in mortal danger.

He asked Mom about her visits from Frank and Madeleine. Mom said, “They’re really just my imaginary friends. Didn’t you ever have one?”

The unit manager confessed he had.

Mom asked, “Did you miss him when he left?”

The unit manager acknowledged he still thought about him from time to time.

Mom consoled, “I have good news. He’ll come back again someday.”

Once admitted, Mom’s delusions about Frank and Madeleine posed few issues. By and large, the nursing assistants believed her when she told them Frank or Madeleine was coming to visit. Once, when I arrived at the assisted living, they had dressed Mom to the nines after she told them she was being picked up and taken to Madeleine’s birthday party. In her hands, Mom held a golden butterfly pin, boxed.

I asked, “Is that for Madeline?”

Mom answered, “It’s mine, but it really should’ve been Madeleine’s.”

Now and then, Mom cried bitterly when an expected visitor failed to show up. Sometimes, she concocted stories to explain what travails waylayed her visitors. I knew she was accustomed to hearing the same sort of nonsense from her father, Frank, who walked out when she was four, and began to re-enter the picture when she was eleven. Nearly always, Frank broke his promises to see Mom and Madeleine, and offered increasingly creative excuses.

My wife Ginger and I were nearly the only regular visitors Mom had. We worked jobs that required long hours, but we visited two or three times weekly and talked with Mom on the phone between visits. It wasn’t unusual for us to visit only to have Mom call an hour later weeping that we hadn’t come to see her in two weeks. Still, Mom was a charmer, and developed friendships with some of the nursing assistants. Though she had selective delusions, her memory was sharp, long- and even short-term. It seemed the only thing she couldn’t quite remember is that we’d been there. Or, perhaps, our presence made her long to be together all the more.

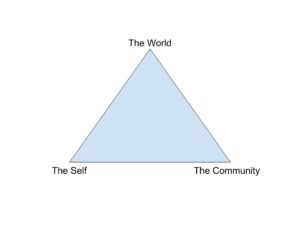

Because Mom was always active in both church and community and had a strong set of friendships created over a lifetime, I tried to maintain the perception that Mom was as good a communicator as ever. I was confident that, if I could maintain that perception, then others would react to Mom as if little or nothing had changed, and Mom would do her best to prove them right. Even though she was geographically at least four hours away by car from nearly all of her close friends, I felt we could make this work, and Mom said, “Let’s give it a wing.”

The stroke had taken away Mom’s ability to write legibly but left her memory, sense of humor, and desire to maintain social contacts intact. Her circle of close friends consisted of twenty people. Periodically she dictated to me a generic letter to be sent to this group. I then prodded her to dictate personalized inserts. My job was keying the generic letter, merging the inserts, and mailing the letters after Mom scribbled something resembling a signature. I told Frank and Madeleine they needed to butt out of our letter writing and they got the message.

Everybody knew I was keying the letters, but Mom’s personality came through, her friends experienced the letters as coming from her, and the letters kept her present in their lives. They could feel the letters came from Mom. Her first began, “Welcome to my estate.” Most friends wrote more letters back than Mom sent out, a few dared to call, a couple even visited. The letters helped maintain the illusion of normal social connectivity while building a record of shared history. And, it gave Mom and her friends a paper record that proved their relationships were still alive. When Mom died, at least three of the friends who came to say their final respects confessed, “She was my best friend.” One added, “I wish I were with her now.”

As we enter the final third of life, it’s common for our circle of close friends to shrink for a multitude of reasons. It’s also not rare to develop impairments that impede our ability to communicate. Mom had selective delusions, but her hearing was perfect, she enunciated clearly, she had a deep desire to nourish connections, and she maintained the knack of promoting connectivity in new relationships. Still, we watched her world shrink during her final three years in assisted living, wheelchair-bound. A project like the one I undertook with Mom to maintain the illusion she was as capable as ever of maintaining friendships really worked. It kept communications going with the close friends she developed over a lifetime and ensured that, when the end came, Mom felt like she was still surrounded by a loving circle of friends.