Before Alaska villages started falling into the ocean, this couple saw change coming

Ray Bane sat quietly on the bank of the Koyukuk River, a winding ribbon of blue so clear that the slant of sun on its pebble-strewn floor bounced back a million shards of light. The river meandered down and along the south flank of the Arctic’s continental divide through the heart of Alaska’s central Brooks Range. Hidden in a grove of willows, Bane breathed in the scent of Alaska’s slender summer. The river murmured in endless, fluid conversation as it tumbled over rocks along the narrow gravel bar.

Bane had not been sitting long when he saw movement along the edge of the willows about thirty yards away. A female gray wolf stepped into sight. Tufts of loose winter fur still clung to her coat. Bane could see by her sagging and shriveled belly that she had recently weaned a litter of wolf cubs. As she ambled toward the river, a pup rushed out of the willows. Four more pups followed, circling the female, chasing each other playfully.

The year was 1971, and Bane and his wife Barbara had come to Alaska a decade earlier as young school teachers to the Native villages of the far north.

While inside the village school Ray and Barbara taught science and math, outside the classroom they became the apprentices of their Native friends and neighbors. From people who lived close to the land, they learned about change through the rhythm of the seasons and the cycle of life. They learned the ways of the Elders, the ones who had been subsisting on this spare and hungry land for centuries.

The Banes did not intend to become activists. But in the 1960s and 1970s, they saw looming changes to the Native way of life and the landscape itself as big oil companies looked to Alaska for domestic sources of oil. Between the advent of snowmobiles, that did away with the quiet pull of a dog team in winter, and the impacts of global warming, where a rising ocean would lap at the front door of Native coastal communities, the Banes saw that some of the last wild places on earth could potentially vanish in their lifetimes. Over their 37-year careers, they would live and work in half-a-dozen villages, mostly across the northern tier of the state.

Shortly after their arrival in Alaska, Ray and Barbara went “bushy.” Many non-Native educators spent winters holed up in small quarters trying to cope with the astringent cold and endless dark. But instead of playing cards with teachers waiting for their next assignment out of the village, the Banes bought and borrowed dogs to assemble a dog team. Ray spent the winters behind his team, hunting seal and caribou with local villagers.

When the principal at the school in the village of Barrow learned that Bane was planning to make a 200-mile round trip trek to the neighboring village of Wainwright by dog team, he threatened to cancel Bane’s leave.

“He considered my activities running around by dog team and going out hunting and socializing with the Eskimos to be foolhardy and setting a poor example,” Bane said. “He was particularly critical of my attempts to learn the Eskimo language and use it in the classroom. He said my job was to help move the children away from their present life and prepare them to live in the modern (white man’s) world.”

Bane made his trip despite the threat and the couple transferred to Wainwright the following year. Wainwright was a smaller, more remote community of Inupiat Eskimos. The Banes always migrated toward living a little closer to the heart of the Arctic.

On that day of the wolf encounter, Bane had been told by villagers that a group of wolves had been sighted on a gravel bar about ten miles upstream on the river. His earlier sightings of wolves as he traveled across the snow-clad landscape with his team had kindled his interest in these elusive and mysterious animals. Bane knew that behind the shadowy myth of wolves was an animal as complex as it was intelligent.

Now as he watched, hidden and kneeling behind a thicket, the wolf pups played tag, ambushed each other, and tumbled in mock battle. One pup tried to run away with a willow stalk which was still rooted to the ground. Running in circles, the fearsome fellow was at times swung off his feet by centrifugal force. Bane observed through his binoculars, rapt by their antics. Then he heard a sound behind him, a twig breaking underfoot. The hair on the nape of his neck prickled. He slowly lowered his binoculars and turned to look.

On a slight rise behind him, standing in the willows just an arm’s length away, a male wolf peered down at him with yellow-rimmed eyes.

“Time seemed to momentarily freeze. The wolf met my eyes,” Bane remembers. “I felt no sense of threat, although I realized that I was not in control of my immediate future.”

The wolf lowered his head and quietly retreated. As Bane watched, he saw several more shapes moving back and forth in the surrounding brush.

Bane decided not to push his luck or further intrude on the pack’s activities. He folded up the camera tripod and stepped out of the willows onto the open bar.

The female wolf leapt to her feet. With lowered head, she angled away as Bane walked quietly in the opposite direction toward his airplane. Paying no attention to his movements, the pups continued their romp on the gravel bar. In the willow thicket, at least two gray shapes kept pace with Bane, escorting him upstream around the bend to where his airplane was tied. After untying the mooring line and pushing off into the river current, Bane let the plane float quietly back downstream toward the gravel bar. As the plane rounded the bend, again in sight of the pups, Bane tipped his head back and let out his approximation of a wolf howl.

“The entire willow grove seemed to explode into a wild chorus of howls that washed across the sky, filling the land and me with an indescribable sense of wildness,” he said. Even the pups lifted their muzzles and cried out a youthful version of their ancestors’ primordial call.

These were the kinds of experiences that sustained Bane when he found himself, just a few years later, a human lightning rod in the middle of a gathering storm – when even old friends would stand up in a crowd and shout to his face, “I hate your guts!”

The discovery of oil on the North Slope of Alaska in 1968 set off a fevered land rush as various stakeholders vied for the possibility of cashing in on enormous economic development. Oil companies wanted to build a pipeline; the State of Alaska had legal claim to a percentage of federally managed lands and was eager to cash in; and the federal government had yet to settle aboriginal claims to the public lands of the state. Millions of acres of Alaska’s untouched wilderness were about to change forever. What that change might look like became a heated economic, political and environmental crisis that would take a decade to resolve, and more than twenty years for the political maelstrom to settle.

Bane had no idea, sitting among wolves on that sunny afternoon, how he would become a flashpoint in the debate for creating National Parks and Preserves across Alaska. What Bane did know was that he and his wife Barbara loved their life in the Arctic. The landscape on which they lived tolerated no sentimental views of wilderness. The realities were stark and formidable, especially in winter, which left no room for mistakes. Yet the rewards, hard-earned as they were, more than made up for the work of chopping wood for fuel and melting ice for water, for the year-round efforts of harvesting sustenance from the land and ice-encrusted sea.

The wilderness was a harsh taskmaster, yet at times the nearly-sentient presence of the land itself left Bane wordless with awe. Where else on earth did caribou migrate by the thousands as they had for millennia, unfettered by human development? Where else did rivers remain as pristine as they had been since the dawn of time?

In 1974 Ray and Barbara planned a leave of absence from their teaching jobs to trek by dog team 1,400 miles across some of the most remote wilderness on earth. They had developed a team with a stellar lead dog, and over the course of the long winter, they built a freight sled piece by piece on the floor of their log cabin. They planned to leave in mid-February as daylight increased, and to stay ahead of the spring thaw as they traveled north along the Arctic coastline. Their plans caught the attention of Zorro Bradley, a coordinator for the National Park Service, who had been assigned to help the NPS and the U.S. Congress better understand the concerns of Alaska Natives who might be affected by the formation of new national parks. Bradley offered the Banes logistical support for their trek, if they agreed to maintain a record of Native winter trail use along their route. The Banes were happy to oblige.

Their trip started during what turned out to be a freakishly cold spring. In brutal temperatures that dipped to seventy below zero, they crossed the Koyukuk Valley and traveled westward toward Kotzebue on to the coast of the Bering Sea. From there, they turned north and paralleled the storm-whipped coastline, often traveling on the frozen sea ice. Along the way, they would visit the villages of Point Hope, Point Lay, Wainwright and finally end their trek at Barrow.

“The thing that sticks most in our memories is the amazing hospitality of the people we met along the way,” Bane remembers. “Without their encouragement and support the trip would have been far more difficult and not nearly as rewarding.”

In the three months it took to complete the trek, village residents offered the Banes a warm if incredulous welcome. The Banes were clearly not typical “Tunniks” (Caucasians) and their travels opened wide their credibility with a people who lived close to the natural rhythms of the land.

Bradley and the NPS took notice. The Banes were a couple who could act as a liaison with Native communities while plans for the establishment of new parks in Alaska took shape. These public lands would preserve for future generations the opportunity to experience wilderness in its rawest form. And nowhere would that be truer than in the Gates of the Arctic, where the Banes lived and worked much of their lives. Here, in the central Brooks Range, the impact of humans was nominal, and wilderness could be left as it had always been, free of modern human development. These new parks in Alaska would be different. Unlike Yellowstone and Yosemite, there would be no roads or facilities, no concessionaires or services to make visitors comfortable.

The Banes accepted the offer to work for the National Park Service. By air and dog-team, the couple explored the far reaches of the central Brooks Range as Ray researched subsistence patterns of Native cultures. As they traveled and worked in remote villages, Ray was careful to explain the purpose of his work. He also talked about the national lands proposals, explaining how legislators in Juneau and Washington were grappling with how to split the pie of the state’s vast public lands.

The Banes’ respect for people and their embrace of a subsistence lifestyle earned them many friends in the rural communities where they worked. But owning a piece of land, or laying claim to it, was a foreign notion to most Natives of Alaska. The people belonged to the land, not the other way around. Many of their friends shrugged and smiled, suggesting Ray ought to look for another line of work. Considering the contentious political climate, and with Alaska’s Congressional delegation strongly opposing these federal proposals, many assumed that the formation of these parks would never happen.

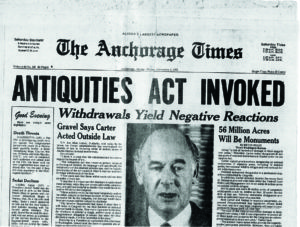

Then in 1978 President Jimmy Carter proclaimed seventeen national monuments, including the eight-million-acre Gates of the Arctic. Considered the single greatest act of conservation in U.S. history, Carter’s planset aside 56 million acres of Alaska land for future parks, preserves and refuges.

“Predictably, all hell broke loose in the hinterlands,” wrote author William E. Brown in his book, History of the Central Brooks Range: Gaunt Beauty, Tenuous Life. “Ray and Barbara Bane, still the only resident field representatives near the proposed northern parklands, received the full brunt of resentment in their community.”

The village store owner refused to serve them. Children threw stones. Their year’s supply of firewood to heat their home was stolen. Bane’s airplane was vandalized in a crime that may have been intended to cause a deadly accident. The NPS urged the Banes to move away to the safer offices of Fairbanks or Anchorage.

Bane refused to leave. He was convinced that hostility was simply a result of fear, and that the media and state’s rights activists were fanning those fears into an inferno of misinformation. Bane stepped into the fire. He invited rural residents, friends, and neighbors to meetings where, with the help of maps and other documents, he could explain what the monuments and the proposed National Parks meant.

“People had legitimate concerns, and I could understand their apprehension,” Bane said. “They just needed to know the facts.” Even after an NPS airplane was torched, Bane remained optimistic. He maintained that the acts of violence were the conduct of one or two hardened individuals. In time emotions would settle and people would come to understand why these lands needed stewardship.

“Having loved the north and its people, having heard for the first time the sound of trucks in the wilderness, (Bane) had joined the fight for what he believed in,” wrote John Kauffmann in his book Alaska’s Brooks Range: The Ultimate Mountains.

Bane sugar-coated nothing as he traveled from village to village explaining the new rules of these wilderness areas. For the most part, little would change to the Native traditional way of life. A big distinction from other national parks around the country, provisions in Alaska’s national parks assured that the Native subsistence culture would remain intact. Unlike other national parks, subsistence hunting, fishing, and trapping would still be allowed. The establishment of these monuments and National Parks meant that these lands would now be protected from a world growing ever thirstier for oil, coal, and mineral development.

Just as importantly, the wilderness would be held in trust as a legacy for future generations—not just a tourist’s semblance of wilderness—but the real deal, where life cycles played out, free from human encroachment.

“I’m a believer,” Bane has said time and again. And what he believes is that whatever changes are ahead, entire wilderness ecosystems need to be kept intact. He likens serving wilderness to protecting the Liberty Bell. “Whether or not I ever visit the Liberty Bell, I’ve inherited it and it’s my responsibility to help preserve it as a legacy of my Nation.”

It was a hard sell at times. Yet the moments like those on the gravel bar with the Koyukuk River wolves,were the moments that helped bolster the Banes’ fight to protect wild places for perpetuity. Enduring friendships, including those with the elders, also helped them weather the decades-long storm. Today, Bane is 80 years old, and his sky-blue eyes still flash with passion about the importance of preserving wilderness in the modern world. He has volumes of journals, stacks of newspaper articles, and hundreds of photos that document his and Barbara’s journey from idealistic young school teachers to strong and sometimes controversial voices for wilderness.

Amidst the memories and the mementos of that early struggle, he says, “Humans have spent more than ninety-eight percent of their history being molded by the forces of untamed Nature … There must be places where the heart of true wildness can continue to beat without technological and bureaucratic pacemakers that diminish wildness for the sake of human convenience. We should be willing to check human actions that ultimately destroy or diminish these last remaining wild places and treat Nature with respect and even reverence.”

Change may be inevitable, especially as the most recent administration unravels many of the protections that were put into place during that tumultuous period in Alaska and environmental history. Yet change can only be sustainable when it is placed in the context of respect for the land, a willingness to preserve our wilderness heritage, and a commitment to be forward-thinking stewards of the earth.