Film is intrinsically about manipulating time—and by extension its subject—in the medium of light. This manipulation requires a phenomenal deception commonly referred to as “the persistence of vision.” It is only with our active participation as viewers that a static string of images flickering across the screen at twenty-four frames per second can perpetuate the illusion of motion. From this most fundamental level to a filmmaker’s editing strategies, moving images are predicated on a visual sleight of hand with which the viewer is entirely complicit.

Questioning the construction of a projected image allows us to question our perceptions of reality and truth—two notions that documentary films allegedly define more accurately than any other motion picture genre. One need not be a Buddhist to understand that the world as we know it is a product of our senses. Truth is not only in the eye of the beholder, it is the eye of the beholder. If “cinema verite” truly reflected the perspective of a fly on the wall, the point of view would appear as refracted as a mirrored geodesic dome.

Perhaps this is the best metaphor then, for illustrating the multi-faceted state of documentary film today. Differences in documentary styles are often a matter of the degree of manipulation the filmmaker chooses to impose. However, in these technocratic times when pictures are as easily produced and reproduced as they are disposed of, it is increasingly difficult to trust our own eyes. Thus, we must question not only techniques, but how the tools a filmmaker employs to create images affects our relationship to the subject—and by extension ourselves.

Even a camera set up to shoot independent of an operator is subject to the limitations and biases of its own mechanisms. Picking up any camera automatically perpetrates a form of manipulation irrespective of the intention to allow the action or events to unfold naturally without interference. From Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North to reality TV, the trajectory of truth in the documentary genre has been less about objectively recording reality, and far more about interpreting it.

Experimental, or “Personal Cinema” boldly reflects a highly subjective view of the world, or the subject it addresses. These films are generally short, non-narrative and structurally idiosyncratic, though the makers often use narrative elements and conventional structures in unconventional ways. Such aesthetic risks usually defy any effort to suspend disbelief. Experimental documentaries take the liberty of formally de- and reconstructing their subjects in order to question the primacy of the image as a conveyor of truth.

A Closer Look: Ken Paul Rosenthal on making Julia Vinograd: Between Spirit and Stone

Interview for Sticks and Stones

by Erica Goss © 2021

I first became aware of the work of filmmaker, Ken Paul Rosenthal, when he made the film Crooked Beauty, which explores artist-writer Jacks McNamara’s journey to empowerment as a person who struggled with their mental health. In this interview, Ken discusses his latest project, a documentary about the legendary Berkeley street poet, Julia Vinograd.

photo by Richard Misrach

Tell our readers about your documentary, Julia Vinograd: Between Spirit and Stone. How and when did you get the idea? How did you hear of Julia Vinograd?

I arrived in San Francisco from New Jersey in 1986, en route to what I imagined would be a career in Hollywood. Intoxicated by the quality of the light and vestiges of post-60’s bohemia, the wealth of repertory cinemas and vibrant experimental film community, and numerous open poetry readings, I never made it to LA. I was living in a Jewish coop and one of my housemates gave me a copy of Julia Vinograd’s The Book of Jerusalem. I was already familiar with Julia’s sharp-witted street poetry from the incendiary Café Babar readings I attended. However, her mythical Jerusalem poems are completely unlike her observational writing. They’re dialogues between God and the city of Jerusalem, who are personified as antagonistic lovers. Part parable, part prayer, part romantic comedy, these poems electrified me.

In 1990, I proposed making a film about these poems to Julia, recorded her reading them, and moved to Israel to live on a kibbutz near Jerusalem for six months to gather images. Over thirty years later, my in-progress documentary, Julia Vinograd: Between Spirit and Stone is the maturation of that dream. The narrative and thematic scope of my film has expanded considerably. Julia emerged from the 1960’s counterculture fighting state oppression with bubbles instead of bricks. She pushed through poverty and multiple disabilities to produce more than 70 volumes of poetry. A lifelong champion of those surviving on societies margins and an enduring symbol of nonviolent resistance through art, Vinograd’s untold story will be presented through the vivid historical prisms of Berkeley’s People’s Park movement, the 1980s-90s post-Beat Bay Area literary scene, and her own incisive, deeply humane poetry.

Has something unexpected, interesting or weird occurred as a result of working on the film?

I love the life that a film project invariably takes on, seemingly of its own accord. Like tending a garden, sometimes you just have to walk away from a film and let it grow–that’s when a tendril can spring forth from an unforeseen place. For example, one year ago I shared a work sample of my film with a colleague. He was watching it with his father who, unbeknownst to me, was internationally renowned photographer Richard Misrach. As a professional picture framer back in the 90’s, I had framed some of Richard’s work and now coveted his iconic portrait of Julia Vinograd from his book, Telegraph 3 A.M. I felt tentative about making a formal request to Richard, so I inserted his photograph into my work sample as a ‘temp image’. He was impressed enough with the work sample to grant me permission to use the photo, along with his other seminal images of 1970’s-era Telegraph Avenue street life.

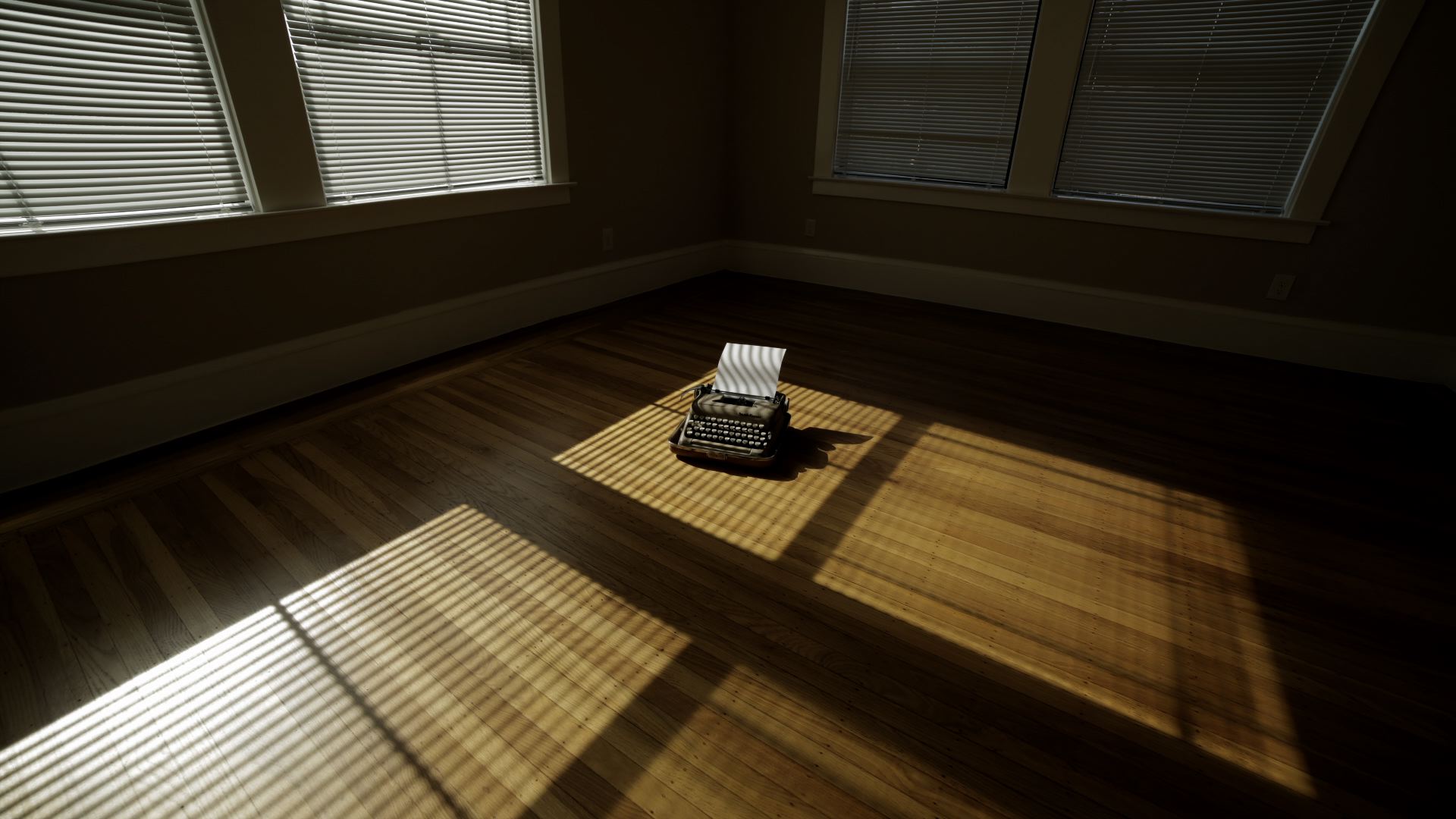

My most profound experience working on the film thus far was spending multiple days in Julia’s former apartment shooting time-lapse sequences of light and shadow moving over her typewriter. No surface was left uncovered in Julia’s apartment when it was occupied. Friends referred to her place as “An incubator of the imagination, a magic cavern.” In contrast, I was sitting on the floor of a vacant, newly remodeled studio, listening to my camera click one frame every thirty seconds for six hours straight while recordings of Julia reciting poetry bounced off the walls. In the moments when I felt spooked, I imagined Julia feeling pleased that her typewriter was back home.

photo by John Storey

frame still by Ken Paul Rosenthal

Please share a favorite anecdote about Julia that you’ve learned since starting the project.

One of her closest friends related a memory of a beautiful young man who stood up to read and his poetry was awful. So, Julia leaned over to this friend and said in a stage whisper, “If only I were deaf, I’d be in love.” Other times she’d say things like, “That person read for just five minutes, but it was twenty years too long.”

I also learned that Julia lived on SSI and often subsisted on one meal a day. She never turned down a free meal and had an appetite that was so voracious, food would end up on her face and clothing. One friend exclaimed, “Julia ate like a pirate. She really dug in!” Another mused that Julia’s DNA is probably embedded in the filth that covers her typewriter keys.

Who have you interviewed so far for the film? How far along are you in the documentary?

I’ve completed forty pre-interviews to date: Julia’s close friends and fellow poets, her building manager and publisher, other local small press publishers, People’s Park activists and Berkeley historians. These interviewees, many of whom have lived in the Bay Area for decades, have contributed essential cultural and political context to Julia’s life, elevating the film to far more than a portrait of an eccentric poet. This timely documentary will explore Berkeley’s legacy of civic uprising, disability rights, and the contributions of the unheralded Café Babar poetry scene to American literature.

Over the past year, I’ve uncovered a treasure trove of archival visual and written materials, including; hundreds of photographs of Julia from childhood through adulthood, footage of Julia blowing bubbles and reading poetry, and radio interviews. I’ve also secured archival stills, audio recordings, and footage of 1969-era People’s Park protests, rare audio and VHS recordings of the Café Babar readings, and so much more!

Tell us a little bit about yourself. When did you start making films?

The seeds of my filmmaking practice were sown in my childhood. My earliest memory is standing in a doorway at the age of four, presaging the power of the frame to shape my field of view. I also remember accidentally opening my box camera in daylight and undeveloped film spilling out. It was gray and glistened in the light like a fish out of water. I was thrilled to discover that analog film was tactile, animate, and vulnerable if not handled with care. My most self-prophesizing ritual of play was staring into the sun until the sensation was unbearable. Like a moth drawn to a flame, I was intoxicated by how far and how furiously I could fly. The interplay of light and dark—both in the perception of motion pictures and as a metaphor for mania and depression—came to fruition decades later when I began making mental health-themed documentaries.

These days, I’m more interested in “seeing the light” rather than being consumed by it. My recent documentaries explore the intersection of art, madness, and the spectrum of difference. These films present the stories of marginalized artists as authentic and redemptive healing narratives. I strive to make emotionally immersive work that touches the mind through the heart with beauty as the gateway. I envision Julia Vinograd: Between Spirit and Stone as an illuminated text. It will feel as intimate as a book in your hand.

frame still by Ken Paul Rosenthal

How has the pandemic affected your artistic practice?

When the pandemic struck, I was laid off from the day job I’d held for the prior six years. So, I’ve been afforded a tremendous amount of time to gather materials, write grants, and edit short work samples. But more essentially, I’ve been inhabiting each day as a full-time artist for the first time in my life. That doesn’t always mean working on the film directly, but experiencing life on a broader stage. Reading in the park, conscious wandering, and getting lost in thoughts are necessary indulgences that nurture, enliven, and inform my creative practice.

Where can our readers find more of your work?

My website is rich with film and bio information, reviews, and interviews. How I Film is a lyrical essay on conscious wandering through natural and urban landscapes. My first and most acclaimed mental health documentary, Crooked Beauty, can be viewed here. I’m reading two Jerusalem poems here at a Julia Vinograd memorial poetry reading.

How can we help your project be successful?

Julia Vinograd felt the pain of the world and wanted to repair injustice with her poetry. With humor, clarity, and compassion, she faithfully chronicled the lives that others ignored. Although Julia has yet to be broadly recognized for these contributions, I believe our collective efforts on this project will revitalize her legacy and join an urgent contemporary movement to re-establish non-normative artists within the cultural landscape.

Your tax-deductible donation will help us complete our interviews—the narrative spine of the film and crucial next stage of production.

Please watch this 6-minute work sample on my fiscal sponsor’s donation page.

You can make a contribution today, in the future, or simply forward this interview to anyone who might be inspired by Julia’s story of resilience, creative activism, and unflagging artistry. I’m deeply grateful for your interest and support.

Look up at night at all the stars

looking down at you, at the part of you that shines.

Always remember to shine.

– Julia Vinograd