A Self Interview about Painting and Philosophy

JW: I’ll use my first initial to distinguish me, John, from you, the painter.

LW: Fine.

JW: Could you tell us a little about your painting process and how it relates to philosophy?

LW: There are philosophical problems everyone shares. Questions about the meaning of life, of death, and of free will, for instance. Questions about our solitude and our capacity for joining with others. Being interested in such things is a feature of being alive as a person.

Everybody has ideas and feelings about their own inner/outer experience. We have strong emotions tied with beliefs and doubts about how to describe ourselves and the world. In my approach to painting, everything happens at the crossroads of the inner and outer worlds of the painter.

JW: Examples?

LW: Think of medieval paintings of demons and angels; Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgement” is a late example of this theme in painting. In the medieval European world most people worried about actual demons and angels. They might appear in paintings commissioned or vetted by the church, but probably in dreams, too, and in the unconsciously created intensity of paintings.

Look at J.M.W. Turner’s “The Slave Ship” (1840). This is cited as an example of maritime Romanticism, and Turner as a precursor of Impressionism. The ship is tossing on a wild sea, and the image first seems dominated by the waves and the sky. Nature appears more august than puny human endeavors. Closer inspection reveals bodies of numerous slaves that have been thrown overboard. The painting seemed chaotic at the time, and formally experimental; later it came to seem beautiful in its dynamic composition and intense colors. It also expressed Turner’s activism against the horrors of slavery. It was meant to be exhibited at a conference of the British Anti-Slavery Society where Prince Albert was to speak. Turner wanted him to take a stronger role in opposing slavery worldwide.

These paintings express radically contrasting world views. They reveal cultural assumptions, but also express emotional fixations of painters and their audiences.

Nobody can escape having what philosophers call a “Phenomenological Ontology.” This means you think the world of your experience includes certain kinds of things and not others. Your world has structure, and furniture. How you feel about those things shows up in your paintings.

JW: Wait. Is a phenomenological ontology a set of claims about what does and does not exist? Or is it more like a practical guide to getting through your day?

LW: If only anyone knew. Philosophers often write as if they are fighting over the correct way to describe the world. Some favor “expansive” (or “bloated”) descriptions, while others insist on “parsimonious” (or “stingy”) accounts.

As for non-philosophers, think of a person whose world includes ghosts, devils, angels, unborn souls, dead souls, teleology (everything happens for a reason), on and on. At the other extreme, think of someone who says nothing exists except energy, or matter, or, in String Theory, strings.

To some extent these beliefs are knowledge claims, and to some extent they are provisional, pragmatic get-through-the-day notes. The situation is complicated by the fact that we begin in childhood with beliefs which are uncritical, e.g., “Santa exists,” or “the Earth is flat,” then gradually we adjust as we gain education.

In a sense though, regardless of how much we study and reflect, we end up with three sets of views: (1) we always work from beliefs that “feel right,” that we call “intuitions,” even though we may struggle against some of these; (2) we hold a more sophisticated set of beliefs, which we adjust “as needed;” and (3) we operate with rough guides to getting through our day which are neither our naive starting points nor our most considered perspectives.

JW: Could you give examples of this?

LW: Take free will and determinism. (1) As children we believe we have free will, but so do sticks and stones; sometimes objects attack us. I trip over a stick, and so I break it. That’s what it deserves. (2) Later, after studying science and philosophy, let’s say I come to believe that sticks don’t have intentions and that my own so-called “free will” is an illusion— we are part of a great chain of causality, and all our actions are determined before birth. Nevertheless, when I go through my day, (3) I hold myself and others morally accountable for our decisions and actions. I get mad if someone misses an appointment; I read about a crime, and a judge sentencing the guilty party, someone who had never experienced anything but cruelty and desperation; I might say “that sentence is too light, the perp needs more punishment.”

If challenged I might say, “I don’t really think the guilty party had much choice. He should be locked up only to keep society safe, or in order to rehabilitate him.” I might not try to defend my intuitive desire for punishment. But as a practical matter I’m not going to say such things down at the cafe, where everyone is calling for blood.

So I start out as a kid believing in free will for people and sticks, move to a position that denies free will to anything or anybody, and use a third set of beliefs in my practical dealings. Each of these sets of beliefs embraces views, and emotions, about how my world is structured.

JW: What assumptions about ontology make their way into your paintings?

LW: I experience myself as a changing process, rather than a thing; I find myself to be full of stories, longings, and influences that come from various times in my life— from a moment ago as well as from my childhood. From my perspective, all of us are fluxes of conscious and unconscious feelings and narratives. One could say, “I am a mess.” Then one might think, “Nature and other people often seem to be calm, cool, and complete.” This is something like Jean-Paul Sartre’s metaphors for one’s experiencing self (a kind of nothingness) and everything outside oneself (kinds of being). I find his descriptions capture ways we often think of ourselves, but not how we always do. So I consider them a “working” phenomenological ontology, category (3) above, whereas I think he considered them the objective truth about the world, category (2).

In any case, this is an example of a kind of ontological preoccupation I have. It is widespread today, but somewhat different from the perspectives of the people portrayed in the paintings I mentioned earlier. Those in medieval Europe who would have seen paintings depicting demons and angels worried for their own immortal souls. People in 19th century England who saw Turner’s paintings of storms at sea, turbulent skies, and blinding suns, juxtaposed with harsh technologies (railroads, slave ships), were concerned with what nature (which was both threatening and under siege) and the industrial revolution meant to them personally.

Despite the centuries and cultural difference between them, Michelangelo and Turner shared certain aspects of their painting processes, which allowed them to describe aspects of their worlds and at the same time to express their deepest feelings.

I paint within a post-Impressionist movement. This approach, like those mentioned above, includes some realism and some impressionism.

Within this approach, one begins with something outside oneself. There is humility in the desire to describe. This, one shares with scientists, and with writers. You honor the world in your wish to describe it in paint, or in words.

When you make the first mark, the motion of your hand will come out of your depths, and the way you begin to draw or paint the scene before you will be different from how anyone else would do it.

Take the first painting, “Baboon by the Sea.”

This pregnant baboon sitting on a rock wall by the sea in South Africa was so moving to me. Her posture and attitude, her tension and attention, called to me. My initial desire was to represent her as she was, or as I imagined she was. I saw her as an early Big Thinker.

As I began to paint I left behind anything like a desire to become a camera. As much as I wanted to depict something in her, I wanted to express something in myself.

JW: So your painting process brings together respecting the baboon and her world with expressing hidden feelings in yourself?

LW: Yes. Describing a subject, the painter receives the light and forgets herself; she is self-effacing. But expressing through paint she is exhibitionistic. This wonderful paradox has the potential to reconcile the feeling of separation between the Being of the World, solid and independent, and the chaotic and emotional Becoming within the painter.

The baboon is alone, high up in the wind, in bright midday sun, with the wide sea behind. She’s thinking hard, attempting to go beyond “I’m hungry,” toward something like “What am I?”

That question might be millions of years off, but maybe she’s having a “proto-question.” She’s flexing her claws on the rock. Her jaw is set and her body is relaxed yet full of energy.

JW: Are you telling a philosophical story about her?

LW: I’m thinking one—that she’s intelligent, and she’s reaching for more comprehension of her life. Unlike many painters in the past, I’m aware that humans and baboons had a common ancestor 30 million years ago. Her line didn’t evolve into humans, but I can imagine her reaching for understanding in a way that our ancient ancestors did.

I identified with her, and as I painted her, my own feelings about being thrust into a place and a time were expressed unconsciously by some motions of my hand.

With each touch of a brush we bring not only a conscious story to the image, but also emotions we don’t really understand well. We are making marks because of things that happened when we were 6 months old, and 11 years old, and before we were born. In the perspective of genomics, we are even influenced by things our ancestors did, what they ate or smoked, for example, which became encoded in the mechanisms which turn genes on and off.

JW: So, you start out to paint a flower, and a lot happens.

LW: Exactly!

JW: Do you set out to engage all these things, a description of something, then a story about it, then somehow an unconscious story about it?

LW: I just love to paint. You should try it. After a few years, I began to see more clearly how painting integrates these elements of becoming and being.

JW: Do you enjoy painting more, with all this in mind?

LW: I do. The more you paint, the better you will get at whatever kind of realism you aim for, and at realizing the conscious stories you are working with. Eventually you glimpse what kind of unconscious stories you must be telling yourself.

JW: This seems complicated.

LW: It gives you self-knowledge and creative expression at the same time. That can be pretty good when you’re having a blue day.

JW: And it’s philosophical?

LW: It clarifies the kinds of things and situations and facts you imagine the world around you to contain, and how you see yourself and others dealing with those things.

This clarifying process is analogous to creative writing and to phenomenological ontology. In all three endeavors you begin with a mysterious desire to understand the world, and you end with a mysterious act of creating a world.

JW: What about the next painting?

LW: In “The Red Door,” the couple is feeling each other’s warmth and electricity as they walk in the chilly air. Nobody else around, the day fading down. The Roman Wall is a massive ancient thing built by slaves. The stains and the light give it a kind of terrible grandeur. But they are headed for that red door.

In the beginning is the world of nature and history, but as soon as you compose the scene, for example leaving out other walkers who were present, and adding the red door, you emerge from being a reporter into being a creator. The painting retains my sense of the quiet street, the day, and the couple. But it also suggests my story about meanings in this painted world, including juxtapositions of inner and outer experiences for the couple.

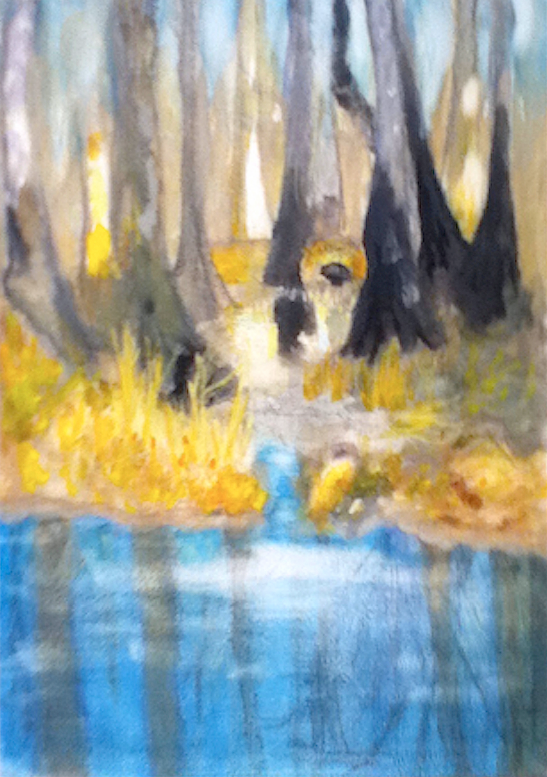

In the third painting, “Cypress Light,” I can smell the fresh cypress twigs and needles on the surface, and I can hear a woodpecker and a wading deer.

The light works its way. All is quiet. It’s a holy place, a sacred place. It’s a world where a person can be alone, listening, appreciating, and wondering. It’s also fragile. I wrote a poem about it after making the painting, and it ends with

—here a boy felt trees protecting forest life—

—water keep those loggers out—

—shade oh shade be blessed, and stay—

This part of the story came up out of my unconscious at the end. The reason this place still exists is that floods have protected it from logging. I do know such places.

This Cypress Swamp painting didn’t begin with standing before an actual place. There is no exact memory of this place, and no photograph, because I imagined it.

But it came from years in the woods as a boy, from standing in such places and listening to the splish of a prehistoric garfish who had been delivered by the river’s flood and now was living out his days as a swamper.

I gave the scene a story of the light, making its way from the back, and of the patch of fern living in a hole in the right foreground tree, and in the world of reflections down in the water.

There is a mystery in these trees, and somehow—to me, now—they exist, they are real. At the same time they are inside my unconscious mind.

JW: And the next one?

LW: Late one afternoon on a street in Ponta del Gato, on the Azorean island of Sao Miguel, I saw these young ones walking home. A teenage sister and younger brother, perhaps. The colors of buildings glowed in the dusk. A palm tree grew from a wall. The street tile geometry gave a touching order to the sea-blown dusk.

LW: Here a glacier-formed boulder rises in the edge of a New England pond. It’s strangely white, and in the foreground wild yellow irises bloom beside dark pools of water. Behind, we have the same primordial light that filtered down 12,000 years ago upon this rock.

This is a place I walk all the time, and yet it’s an enchanted fictional place, and its frame is a portal to a world I touch every time I see it. Somehow in this painting I’m living in the late Paleolithic, passing this rock with my spear.

I began with the light and dark masses, and the fine shifts of color. Soon I felt I was in a holy place of long ago.

These shapes, these darks and lights, this long history and these fresh blooms just held me there. In my story the dead branches on the right are reaching with the energy of their recent lives, and the light is finding or making a thousand greens.

The story is about deep time. The unchanging rock and the unchanging light.

JW: But the very much changing forest. And the changing consciousness of you, from stone age hunter to painter.

LW: Partly changing.

JW: Then comes the exploding galaxy.

LW: Exploding and recombining in a wild birth of stars. To think we live in the time of NASA, and we can see this moment as it was many, many light years ago. Ontology must make way for all this, and my feelings about the galaxy, and my drive to paint such a scene in watercolor on a 4” X 6” piece of paper.

This painting originated after viewing NASA photos of distant galaxies. Rather than the exact shapes of a place and time, I was moved by the feeling of immense explosions, gravitational warpings, and creative intensity surrounded by dark space. After developing the light/dark values to suggest depths, I built up color areas by tapping a toothbrush loaded with watercolor.

We came from this, you know?

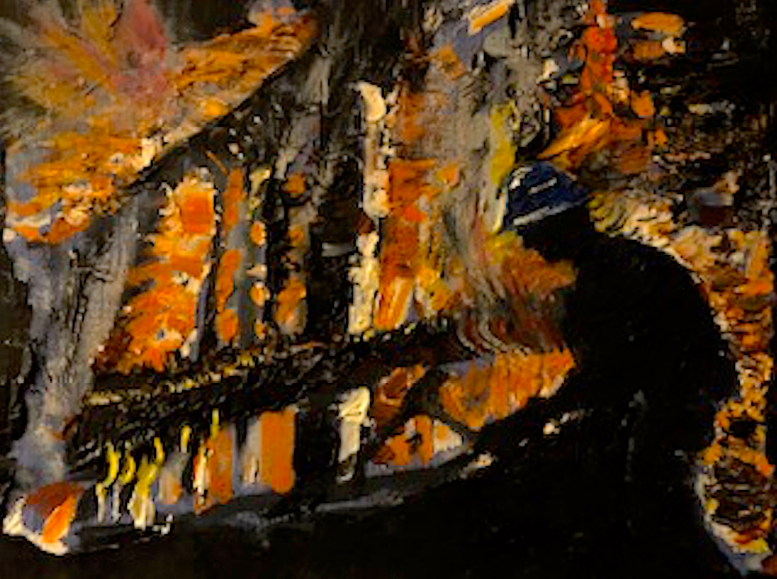

JW: The next painting you discuss is of the firefighter at night, with the forest falling down next to him.

LW: This painting is from a photo taken in 1957, in Montana. It was given to me by the smokejumper who took it. I was drawn to the young man in silhouette, to his fierceness and dignity, to his fighting the fire so close to its explosions.

Friends of mine have worked as smokejumpers in Montana and Alaska, and I have worked on fire-prevention forestry crews in Idaho. One summer I was a fire watcher in a tower, high in the Rockies. The obvious story of this painting is about danger and courage. As I painted, I gained clues to less obvious elements. I knew I could not have stood my ground so close to this hell. The hot wind and burning smells were frightening. How could he do it?

The dark shadows and the red-orange fire are of course strong visual contrasts, but I think the darkness represents (unconsciously) an underworld of agony, fear, and struggle for courage. I don’t know everything that this picture means to me. Every time I look at it I measure myself against the firefighter. I come up short, and the painting stirs insecurities. But there they are, chased up and exposed to light.

JW: The next four paintings are rather peaceful landscapes.

LW: This is where I fished as a boy. I spent endless days alone in my boat under that open sky. The borderline between water and swampy land was a lively place of frogs and snakes and birds. The cypress trees were stark and, to me, beautiful. Reflections down in the water came alive. Above all, the stillness of the place was strong, almost shockingly peaceful.

As I painted, I sought the colors and values of the cold sky, and the warm grasses, the dead-looking trees juxtaposed with the rich life in the water. There were always pops of air, a turtle head appearing on the surface, the dorsal fin of a largemouth bass twisting, and shadowy fish shooting by. A kingfisher would fly in scoops. Late in the afternoon, near the time my father would meet me, great horned owls would ring across the surface. This painting brings those memories, and a sense that this lake—with its silence and cypress smells and long thin swimming snakes—lives inside me.

JW: The next one, “Holly and Cedar” is more intense.

LW: I hunted here, enjoyed great friendships here, and a share of landline enemies. A defining landscape for me, which has filled my life, my books, and even now my dreams.

The light in the distance suggests a trail on which deer approach.

Painting this scene, using a pallet knife on the tree trunk edges, helping them emerge, brought me happiness. It also brings time’s sorrow.

Making this painting was an act of love beyond any rational understanding I have about it.

JW: Then comes the prehistoric one.

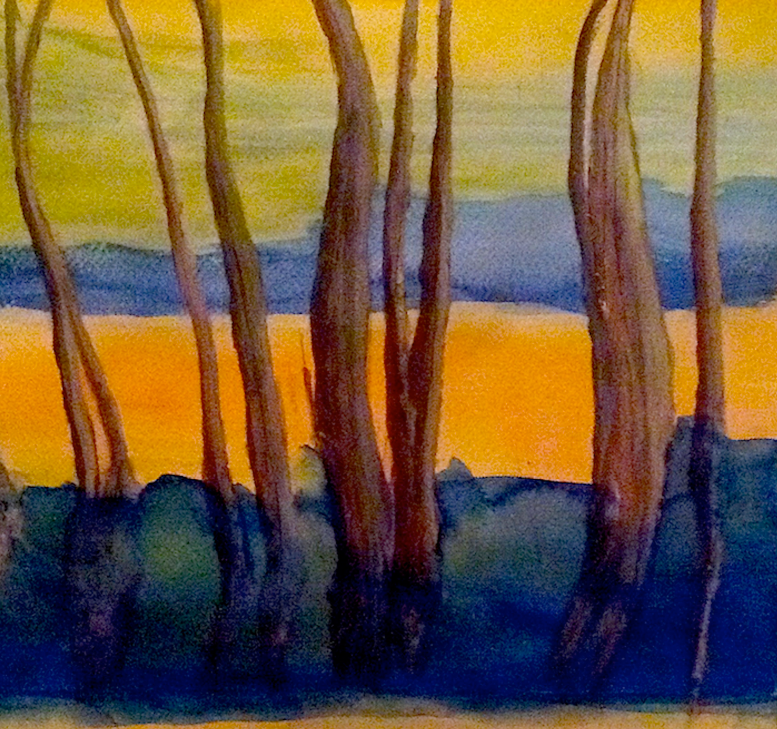

LW: It originated as I watched a slow December sunset at Bluff Lake, in Mississippi. As I painted, detail dropped away and I imagined the life forms of a few hundred million years ago. Even before flowers emerged on earth there were beautiful dawns and sunsets. But there’s a feeling of unknown danger. I’m a visitor to this ancient world.

JW: And with the following painting we’re back in our present.

LW: This place is near my house. I felt the sky of an approaching storm as a cold place, emotionally. No company for humans. But the wildflowers —they aren’t exactly wild in that they were planted by humans— and the barn are cozy. Yet the sky could do anything to them.

JW: And number twelve takes us back to the woods.

LW: I’ve painted this place, the Cat Slough, quite a few times. Once I was high in a tree here, when a mother bobcat with two almost-grown young ones slipped through the wet leaves beneath me. The mother and one of the offspring glanced up and took off. But the other bobcat froze and stared, displaying an aggressive, potentially fatal, curiosity. Then he bolted as well.

The story is of a pathway, for light and for birds, contrasting with the underworld of reflections, and the dark, wet trunks which speak of floods, high water for days, and rot causing weird beautiful forms in the cypress and tupelo trunks.

I find this irresistible on a visual level. But it’s filled with meanings only partly available to my waking mind.

JW: And number thirteen?

LW: This was a very old Cattle Dog, as they are called, guarding the nuns on a hilltop in Sao Miguel, Azores. He barked incessantly, loudly, and hoarsely.

He was fierce, and dedicated to his task.

I felt badly for him. I was initially taken by his shape and colors, and the faded green of the metal gate which closed his prison. I wanted to catch his military tension, and his desperate eyes. Unlike the baboon of the first painting, who seemed inspired by her freedom to attempt big thoughts, this dog was bound into a life of rage. These feelings I had about the animals came to the surface as I worked. Partly, they expressed our cultural moment— in the perspectives of evolution and of animal rights. But the unconscious stories I discovered involved empathy for these beings, and made me realize that I was thinking of them as I think of myself— a series of inner stories juxtaposed with an outer world that seems strange.

JW: Well, I hope you’ll keep painting.

LW: Me too.