“She’s beautiful,” I said.

“He,” Bill said.

“Right,” I said, “I always think of them as feminine.”

I was brushing him with the curry comb, and his flank was warm and smooth and his eyes big and soft like a romantic heroine.

Even with his penis he was all grace and poise like a Degas ballerina, and I too wanted to paint him like a girl balanced on her toe, my ancient love returning to when I was a child penciling him on the wall by my bed that my mother would leave until her Saturday cleaning when she would wipe him away and let me draw again.

I was five years old and I had just seen him in a cowboy movie in the little theatre down the block with Roy Rogers, whose horse, Trigger, was also a palomino.

Then I would see him brown with a black mane wearing a burlap and harnessed to the ice-man’s cart like god who was made a slave, the delicious odor of his nuggets steaming on the cobbles by the trolley tracks and the plumes of his breath like a blessing on my little hand.

Bill too was a city boy and had always lived in cities until he could afford a fixer upper with his wife here in Verdi, a little hamlet near Reno in the shadow of the Sierras where his corral was big enough not only for “Yellow” but also “Rocky,” the wild grey and white mustang he had bought cheap and then tamed.

He pulled them in their carriage with his truck to the trail up the mountain where he would ride Rocky and give Yellow to me, and since I had never ridden before he showed me how to hold his mane and slip my sneaker into the stirrup and climb into the saddle.

“You look like you’ve been doing this all your life,” he said.

“I have,” I said, “I’ve been watching it in all those westerns since I was a kid.”

“Just hold the reins loose and let him lead you.”

He knew the trail, Bill said, and Bill and Rocky would follow us.

“Don’t let him eat,” Bill said when he stopped to munch a tuft of grass near the trail.

“Why?” I said.

“He’s working,” Bill said. “We’ll feed him when we stop; just keep him at a steady pace.”

But he stopped to munch again, and he was too powerful for me to pull him away.

“You’re spoiling him,” Bill said.

And when he started to gallop I had to pull the reins to keep him from galloping too far.

Then sitting with my back straight like I would on a meditation pillow, I felt his energy rise up my spine to the top of my head.

“Pure life,” Virginia Woolf called it, the same pulse and power of D.H. Lawrence’s horse in St. Mawr and the myth of the centaur.

“How old is he?” I asked Bill.

“Twenty,” he said.

“How long can he live?”

“He can live to thirty.”

“He still feels strong,” I said.

“He is,” Bill said.

And feeling him under me like my other half that I always wanted to write about, I had fallen in love with him, the pure life of my longing while my body aged toward death. He was twenty years old like I was sixty and his own life was half gone, yet he was still strong enough to carry me up the mountain.

We rode up the trail with the big pines leading to the lodgepole like in the Peckinpah film, Ride the High Country. We were as old now as the actors Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott and the mountain was in the same range, and Bill quoted what McCrea said to Scott as they rode toward where McCrea would be killed:

“I just want to go to my death justified.”

It was a great film, and Bill and I loved it with the other half of us that loved books and films and was part of the life in the valley below.

We were high enough now to see the valley spread into the city as if from the mountain peak in the Buddhist metaphor of enlightenment that would rise above samsara while still rooted in dukkha, the air now clean and clear like laughing gas.

I visited Bill only once a year in those days, and it was always like a holiday from my life in Berkeley when I would time it to fit into his weekends away from his law practice in Reno. He too had been a writer in our youth, but he had given it up to become a lawyer around the time he stopped drinking.

The last time I came he had just bought a small motor boat and towed it to a lake to try it out, and it was also my first time in a motorboat. He was only three years older than I but I always thought of him as a big brother who would teach me new experiences, and I had loved him from the first day we met back in Rutgers.

Kerouac had just published On the Road and Bill was the first of our Rutgers gang to hitch across country that would later lead to my own trip, and he had worked his way abroad on a steamer and lived in the Latin Quarter with Gregory Corso in “the Beat Hotel” on Rue Git-le-Coeur where I would also try to find a room; then living in Paris he befriended James Baldwin and William Burroughs and James Jones, and when he returned to the States he introduced me to Baldwin and gave me Jones’ old trench coat with all those buttons and lapels that Jones had given to him.

I moved to London after he returned to the States, and he wrote to me when he was in Reno the first time. He had loved the west from when he hitched there, but he was still restless and asked if I could help him move to London, and since I was leaving for Stanford I gave him my film teaching job and my digs in Spitalfields; then I didn’t see him until four or was it five years later when he had passed the bar and was living with his first wife in North Beach.

He had been drinking heavily since he left Rutgers, especially when he was in Mijas in Spain where wine was so cheap, and he was really an alcoholic by now; yet he hadn’t joined AA until I came to Berkeley, and I gave him three hundred dollars for a “funny farm” to dry out.

It helped for a while, but it was a long haul to leave his wife and find his new one in AA, which was around the time he got lucky with a lawsuit and bought the fixer upper in Verdi and learned how to keep a horse and even tame one.

We rode until we were almost at the crest where we stopped for lunch by a stream, and I helped him strap the front ankles of Yellow and Rocky so they wouldn’t move; then we fed them with the canvas bags of oats that they nibbled and munched in that delicious way animals have when they eat, their big hairy lips so endearing l I wanted to kiss them the way I wanted to kiss my mother who had become like them in the nursing home where her body was shrinking as if back into the realm of rocks and trees.

The horses were like my mother and my mother and they were like the aspen and the chokecherry and the scattered pine cones where we sat on some rocks and ate the tuna fish sandwiches I had made in the morning with celery and mayonnaise, the pattern of the little twigs by my foot the same as the swirl of galaxies.

Then how delicious were the tuna fish and the slices of tomato on the rye bread and the death of the fish, and the tomato seeds and rye seeds were like the death of stars and my mother’s and Bill’s and mine.

“We should have bought some chocolate,” Bill said, and we sucked little hard candies with water from our canteens instead. We had been riding for about three hours and Bill was impressed that I wasn’t tired or sore.

I wish I could write our dialogue now like Hemingway with his friend Bill in The Sun Also Rises, but I can’t; no one could really, not with the same music he worked so hard to perfect.

Bill loved him as much as I and said he was like a father to us, despite the sickness of his killing and what made him kill even himself. Bill too had lost his father as a kid, and like so many of our fatherless generation we adopted Hemingway’s own generation who were the age of our fathers. We were in the high country with the horses and the wildlife, but we still remembered the years of books and cities.

Then we hit the trail again, and as it circled the peak, my trust in Yellow vied with my fear of heights while his hooves clicked on the narrow trail so close to the edge. Hiking on foot I wouldn’t have been so afraid, but riding so high on his back, I had to keep from looking down at the great expanse that lay so far below, and I felt like a falcon perched on a crag.

My life was in his hands now, that is on his back, and he seemed to know it. His brain was smaller than a dog’s, Bill had said, or the part dogs share with us, but there was the other part Lawrence was always writing about that Hemingway couldn’t, the deeper part in a horse when he carries someone like me so close to the edge, as if it would guide me home.

Then he stopped and I almost tapped him to continue before I remembered that he would stop when he wanted to shit, and as I looked back sure enough his tail was up, and the turds dropped in that happy way that would look disgusting had they come from a human.

It was hot in the open now, and my lower half hugged him close while the rest of me bobbed and meditated. What pleasure could be more satisfying? With a woman maybe, but he was my woman now, so warm and full of life.

Then the trail turned and we looped down into the trees where he wanted to gallop, and it felt exciting when I let him, except for my balls that I had to keep pulling up so they wouldn’t bump on the saddle because I didn’t know how to ride smoothly. Was that why some women loved to ride, that bump between their legs?

Some men are afraid of horses, Bill said. They don’t want to lose control to someone more powerful, but women often feel the opposite. They love that kind of power, he said, and can surrender to it.

Maybe I was like a woman, since I too surrendered to it, at least with Yellow, and it was not surrendering to the bigger Yellow that had caused me so much loneliness and despair.

We swayed and bobbed, my old friend Bill and I, riding down the trail on our exciting horses, two old men like Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea, until we returned to the truck and looked up to where we had been.

We had been riding for six hours, and I felt high with my achievement.

“You did good,” Bill said, my dear friend Bill who was like a big brother.

“Thanks to you,” I said.

It would be the last time I would see him.

I couldn’t make it the following year; I had planned as always to drive up to see him at the end of summer, but he kept postponing my trip until autumn when I couldn’t make it, so I was going to wait until the next year when he suddenly died.

He had lymphoma, I learned later, and his wife, who didn’t know me well, didn’t let me know he was in the hospital. Nor did she let me know of the wake, maybe because she thought a mutual friend would tell me about it, but the mutual friend didn’t either, and I didn’t learn of it until a week later.

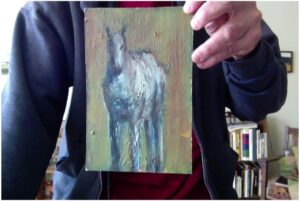

And so, I didn’t get to say how much he meant to me until I began writing these lines about his horse, Yellow. He had loved horses from way back when his friend Polk trained them in Virginia, and he later wrote a story when he was still in law school about how it felt to kiss one, and I saw the story come true when I watched him kiss Rocky.

“Hey, Big Fella!” he said one afternoon when he was approaching the corral where Rocky had lowered his head to greet him, and he kissed him on his big and hairy lips.

He loved to kiss what he loved and even slobbered me once on my cheek one night in London when he was very drunk and dragged me through Soho looking for one of his girlfriends.

He had lots of girlfriends and was never without a woman. He was blessed with good looks and a cheerful personality, but he didn’t stay with any of them until he met Joan in AA and settled down with her in Verdi. He was around fifty by then and she was about ten years younger, and they did try to have a kid, but it didn’t happen.

They had each other instead, and they built their little homestead by the mountains with their dogs and cats and the chickadee who perched on the feeder on the porch, and of course Yellow and Rocky.

He had always been a nature lover even as a kid when his family moved from Queens to a suburb of Newark near a marsh where he would wander like a young Wordsworth, and though his restlessness would drive him to the cities of his drinking and addiction, he finally made it to his heart’s desire.

I remember him now with as many details as in a novel, but it’s a poem I really need to write, a kind of pastoral elegy with a horse instead of sheep.

I don’t want to write the story of his life, no, I want to write what his life meant to me.

One morning when he was staying with me at the cottage in Berkeley after leaving his ex and joining AA, he said he was going to buy a pack of cigarettes in the Yemini liquor shop around the corner, and he didn’t see me following him.

Then as I watched him ask for a half pint of vodka, I said:

“Don’t, Bill.”

And he didn’t.

He never forgot that, he would say to me in the following years, not about stopping him, but why I wanted to stop him.

He was my friend and yet more. The bird a nest, the spider a web, man friendship, wrote Blake.

He died a year before my mother when he was only 68, and my mother died the following spring when she had turned 101; then as I drove to her burial, the green of the great valley was turning a glorious yellow that was her favorite color.