I have been contemplating this title for over a decade.

After the loss of my late partner of fifteen years, reflection on our joint journey and each of us as individuals had become the driving axis in my grieving process. We were a gay couple. I came to the West over twenty years ago. “Love” and “Freedom” are the two shining words attached to the heartstring of many new immigrants, including myself. I landed at midnight in New York City. I still vividly remember the sensation radiating from that summer night, blended with the warm air, unquenched by the exhausting long flight. I dragged two oversized luggage from the airport lobby to the curbside, hoping to squeeze them into a yellow cab. They were tightly packed with everything I imagined being useful in a foreign land. My first western experience was living in a college town. After being immersed in the informing and encouraging milieu, I came out of the closet the following year. The desire to experience love at once took over the priority of my path. Four years later, I met my late partner. We met when we both already had a life portfolio of decent length, which shaped us as independent men. My late partner had married with children, divorced, survived the AIDS epidemic, and eventually became a gay activist. Though there were ideas and models that we were raised and environed with, we started our family without an assumed social frame.

We were once married. We took the vow. However, as I look back at the fifteen years in the book, I must confess that our relationship had been more of an exploration striving to achieve and maintain a balance between us, a balance between the committed intimate partnership and the individual free space. I have a full-time thriving career, while my late partner lived on limited disability compensation. Though challenged by the health condition, he led an independent life and actively engaged with the community. However, our social dynamics, including financial equality, suddenly changed once we moved in together. We loved and cared for each other, we believed in the vow we took—no question about it, but we also struggled. And that struggle, we both would agree, was one of the signatures of our fifteen years.

Our relationship had lived through the crucial phase of the marriage equality campaign. We, as a couple, ardently joined the battle. We were one of the gay marriage ambassadors in New York State. Our photo captioned with our stories was on the public display. Since its first winning legalization in Netherland in 2001, gay marriage has now been legalized in thirty countries and territories, mostly in the West. When people read the title of this article, the immediate reaction, as I imagine, would be that we cannot turn back the clock—that is not my intention. I have shifted my views on gay love and relationship: from a younger gay immigrant who was determined to experience love and freedom to the middle-aged me with years of a shared household with an American partner. Many gay men who have been in a long term relationship would share a similar sentiment translocation.

My intention is to shift the focal point in the debate about gay marriage: from fighting for equality to discussing the challenges modern love relationships are confronted with—gay and straight. How are we to make a relationship satisfying and long-lasting? A marriage certificate is not the warranty. With the widespread winning of marriage equality, I hope that we are ready to offer our perspective as a social minority.

In her landmark book Marriage, A History: How Love Conquered Marriage, social study scholar Stephanie Coontz wrote profoundly, “Marriage has become more joyful, more loving, and more satisfying for many couples than ever before in history. At the same time, it has become optional and more brittle. These two strands of change cannot be disentangled.”

The struggles manifested in our two-man household reverberated with this dilemma.

Love and freedom unquestionably remained central amid all the highs and lows throughout our partnership, a partnership between an immigrant and an AIDS survivor. However, twenty-plus years later, I have come to understand that, on an individual scale, love and freedom can be two contradicting words. The kernel of freedom sprouts self-sufficiency and self-security. In contrast, love grounds on compromise and demands the exposure of vulnerability. Under the roof of a modest ranch brick house, our mundane struggle was not to love or to be free. Instead, it was to attain the balance between the two. We are often trapped in this dilemma, a phenomenon that is very prominent in the gay community. Some gay men thus resolve to lead a single life. Some couples continue to struggle even after many years of shared life, admittedly my later partner and I being one of them.

Marriage Story (2019), the award-winning film, depicted the divorce proceeding of a New York City theater power couple, a stage director and his actor wife. At the ending of the film, the divorced husband read his ex-wife’s note expressing her feelings towards him and the breakup. The quote reads heartbreakingly, “I fell in love with him two seconds after I saw him. And I’ll never stop loving him, even though it doesn’t make sense anymore.” Yet the screenplay made it crystal clear that the wife felt the suffocating loss of her career ambition in her married years. Only after the divorce did she make a successful debut as a director on her own. Here is an online film review’s title: “Marriage Story” expertly blurs the line between love and separation. Indeed, art and literature often blur the line between love and freedom.

Throughout the LGBTQ marriage equality campaign, even to this day (and probably in certain future), the most widely expressed sentiments– “love is love” and “our love is no different” –are powerful rallying cries. These messages are powerful, and thus imply to the community that marriage is about love. “Love is love” is indeed successful in gaining public sympathy and support. However, this winning point also enforces the idea, among both supporters and opponents, that marriage is the penultimate ideal of all models of human relationships. Therefore, civil union must be a second class. Unlike popular public opinion, scholars have struggled to reach a consensus on the definition of marriage. They do, however, all agree that marriage has been through changes throughout history. Its history, in modern times in particular, demonstrates a constant shift of balance between social stability and personal fulfillment. This fundamental dynamic of marriage as a social institution had received little attention in designing our equality slogan.

Before gay marriage was legalized in New York State, many institutions had policies offering couple benefits to LGBTQ persons proven in a domestic partnership. When gay marriage was recognized in our state, some workplaces initially reacted by removing those policies and requiring a marriage certificate for all who wanted to claim couple benefits. This aroused an outcry in our community—not every LGBTQ couple elects to get married. The direction of the argument had deviated. The diversity of human relationships should be valued, and that suddenly became the spear of our debate. This argument, in essence, elevated the status of civil union and co-habitant, but made it to the surface only after the winning of marriage equality. Much less documented and remembered, this episode revealed that we understand the evolving nature of marriage.

I now want to argue that “love is love” and “our love is no different” are phasic in the LGBTQ movement. At its current stage, our goal is to gain public sympathy. The majority of the stories brought to light are used to demonstrate discrimination, such as struggles related to inheritance, pension, health care proxy, and immigration rights, etc. They are to convince the public that our love relationship suffers because we do not have what heterosexual couples are entitled to. Many LGBTQ couples indeed have to experiment because traditional relationship norms and social protections may not readily fit or be available to them. In my opinion, the stories of those experiments in the LGBTQ households are shadowed by the “our love is no different” banner.

A recently published social study may prompt us to re-examine our favorite motto. Appearing in the Journal of Marriage and Family, the study found that gay couples are more satisfied with their partners than heterosexuals (Garcia & Umberson, 2019). Are gay couples gayer?! The researchers argued that gay couples are less subjected to the male-female difference imposed in the traditional marriage model. They are more likely to share domestic chores and have a stronger tendency to openly discuss feelings and respective preferences, including sexuality. Without assumed social norm heritage, negotiation is more of necessity, and their relationship dynamic is more fluid. They even spend more time with children than heterosexual couples do. All these help develop deeper intimacy. I believe that many gay couples could fill in personal notes to support the research findings. I remember that, just a few months before his passing, my late partner wrote me a candid letter stating that he still had dreams and plans beyond our household perimeters. Throughout our relationship, we had many expressive discussions, including in writings to each other.

In one of his popular performances, standup comedian Gabriel Iglesias made a funny but very insightful social comment, “… Let me tell you the reason why I would be an amazing gay partner. The level, the level of communication between two men is so high. I might actually get an answer. There might be clarity and understanding…” (@2.30). Gabriel Iglesias is a straight man.

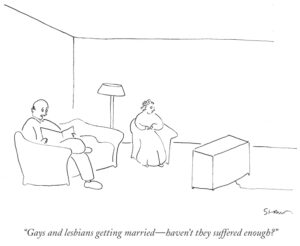

Gay couples certainly have their challenges, but our relationships, in the private and intimate dimension, may suffer less paradoxically because we are less entitled to the social norms. I recall and echo the sarcasm from a cartoon printed in the New Yorker: the heterosexual couple was sitting in their living room, drawn in simple lines and dots. The husband was reading the newspaper, and he commented, “Gays and lesbians getting married—haven’t they suffered enough?”

Another winning argument in the marriage equality campaign is that married heterosexual couples are entitled to hundreds of rights that were denied to gay couples. For the following questions, I’d like us to ponder together: Are most of these rights in place to enhance a marriage’s stability? Would more rights necessarily make a marriage happier? With so many rights bundled with marriage, why do half of the unions still end in divorce, a probability equal to flipping a coin? How do we think about the messy and expensive divorce process? Except to some fundamental rights, such as immigration and healthcare proxy, can modern couples negotiate their own contract by consulting the law?

When marriage is secured by the law and honored with the social status, it says more about the society we live in. A diamond engagement ring and a fancy wedding represent not only the sincerity of the ceremony, but also a powerful social statement. Some LGBTQ couples had to experiment with their relationship long before social protections were available, and many had long-lasting companionships. Those civil unions speak more about the couples. Contemporary LGBTQ couples still have to experiment as the husband-wife model usually is not a fit. These gay love stories have not been well written or well understood. Now it is the social study scholars who open the Pandora’s Box. Stephanie Coontz commented, “In fact, it appears that many different-sex couples would have happier and more satisfying marriages if they took a few lessons from their same-sex counterparts.” Messages like this were unthinkable during our equality fight. In my opinion, they belong to the future phase in the LGBTQ movement: look, our community has life stories that may help understand and improve marriage and love relationships!

As the crowned monopoly, marriage used to dictate how people organize their life. These days are on the final chapter with the marriage rate dipping, divorce holding a 50/50 chance. Co-habitation and other familial models are becoming more visible and acceptable. The human love relationship continues to evolve. In fact, single-person households are on the rise and may soon hold even with two-person families. Another recent study’s result is even more revolutionary, showing that single people are getting happier than in the past. Singles are more satisfied with their lives when they grow older (Boger & Huxhold, 2020). The stigma about singles may slowly be eliminated: people can organize a happy and meaningful life without a committed life partner.

We may boldly imagine that, in the distant future, a new designation covering all human interpersonal relationships may crop up in the urban dictionary. Under this new umbrella term, marriage, still being regarded as the form with the highest commitment, will stand next to civil union and other family prototypes. One of my friends said, “That is way ahead of our time!” It certainly would be. However, the intention behind this essay’s title is not to turn back the clock or predict the future, but to offer a new perspective to the ongoing debate and hope to have the discussion open wider.

![]()

Sources:

- Garcia, M.A. and Umberson, D. (2019) “Marital Strain and Psychological Distress in Same-Sex and Different-Sex Couples.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 81: 1253-1268.

- Anne Böger, A. and Huxhold, O. (2020) “The Changing Relationship Between Partnership Status and Loneliness: Effects Related to Aging and Historical Time.” The Journals of Gerontology, 75(7):1423–1432