I had a white 1960’s Mustang the year Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated (didn’t just about everybody?) and it had Iowa plates, red letters on white. I built up a “Y” on the plates out of acrylic paints, so they read “IOWAY.” Civil disobedience of a mild and passive sort. It was noticed. Once that I know of. A guy on a motorcycle behind me, at a stoplight, had zeroed in on it and he was comparing it with other plates in the wait line. He looked quite puzzled. It was a good fake.

For no other reason than I didn’t want to be in Iowa, I’d vowed I’d never live there, or Detroit. I did live in Iowa and later wished I’d attended the Iowa Workshop. I never lived in Detroit, but did work there on some Westin Hotels and Renaissance Center. A radio station, too. WOMC. I named it The Big O, and another copywriter came up with the line, “What would Detroit be without the big O? Detrit.” A woman nearing childbirth named her kid Detrit upon hearing that commercial in the hospital. I digress. I guess he’d be about fifty now. If you’re out there, Detrit, I’m not responsible but I know the guy who is. Oddly enough, he lives in Iowa now after a long stint in Japan. Hell of a creative guy.

The day MLK was shot, my stepfather was in the hospital in KC undergoing a fairly dicey operation, so I made preparations to show up.

I drove my white Mustang with red and white plates to Kansas City the day after MLK was gunned down in Memphis. The man accused of shooting King, James Earl Ray, also drove a white Mustang with white Tennessee plates. Not even the King family believes Ray was the killer, but that was the official poop, like Lee Harvey Oswald, like Sirhan Sirhan. Sooner or later, though, this kind of “solve n’ seal” propaganda gets a sideways look, and a question or two because none of the “facts” jibe and real facts uncover more real facts. But anyway, I drove from Iowa to KC and when I neared the Country Club Plaza, a famous shopping area there, after skirting burning areas of downtown and midtown, I was waved down by a National Guard officer in front of a phalanx of kneeling, aiming marksmen. Aiming at me. I stopped. I was told to get out, hands on my head.

“White Mustang, white plates,” he said, after questions, identification, search. “That’s what the whole country is looking for. Sure are a lot of them around.”

“Popular vehicle,” I said as he checked out my sheriff’s patrol get-out-of-jail-free card. I had such a card due to belonging to the local sheriff’s patrol in an auxiliary mounted capacity, being called into service when it became necessary to search for lost persons etc. on horseback in rough country. We also rode in their parades, took part in crowd control practice. [See author’s article “Racist by Default” in The Good Men Project. -Ed.]

“Keep your weapon on the dashboard in plain sight,” he said, after examining my Beretta, which I’d had since college days, a loan repayment.

“I can’t guarantee that they won’t confiscate your piece, but if it’s hidden and they find it, they sure as hell will. Good luck.”

He hadn’t noticed my Ioway plates other than their similarity to Tennessee plates.

He patted the top of the Mustang, as in a movie, and I drove off. I was stopped once more in Leawood, Kansas, the Kansas City area subdivision where my parents lived. The Leawood police were much more nervous, edgy, and followed me to the door, where I knocked, was admitted by my mother. They then left.

The next day, driving through the Plaza on the way to the hospital, I marvelled at how like this, in the beginning, Saigon must have been: troop carriers everywhere, weapons bristling, fatigue-dressed foot patrols, police cruising. The sidewalk cafes were fairly full, the mood undampened by the presence. Girls waved at the soldiers. It seemed to me there was an air of forced, nervous gaiety. Parts of the city were burning.

I recalled driving through the same area in a Porsche in earlier days, a car full of blacks pulling up next to me at a light, the driver hollering, “Hey, you one a my boys, right?”

I hollered back, “You bet!” and waved. And the light changed. The guy in my passenger seat, a rabid racist at the time, said, “What the fuck was that about?”

Many years later he lived in Los Angeles masquerading, or perhaps transformed, as a stone California liberal who accused me of being racist and homophobic, though I am neither, never was. The N-word had come easily to him back in the day. When I’d tried to dissuade him he’d said, “Tell me about it when they’re fucking your sister over a garbage can in a back alley.”

The incident with the car full of African-Americans in 1960 or so, was the result of some beers bought and reciprocated in Milton’s Tap Room, a KC jazz hangout, and some good cheer between black and white patrons. They remembered my car and a friend’s red Jaguar XK-140 roadster when we left, and joked about it. Not exactly stealth vehicles. That friend got the same treatment when paths crossed. We felt it was progress in the right direction. We enjoyed being accepted as “their boys.”

Then Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed. Someone thought he was too powerful, too persuasive, too captivating. Too right on the money. Too dangerous to the bullshit status quo. So he was killed. And I repeat, not by James Earl Ray. Not in my book or that of many others.

Some intrepid whistleblower may yet give us the answers and end up in prison like Chelsea Manning or Julian Assange for daring to suggest that war crimes are committed right here. Because, make no mistake, outright war was declared on JFK, MLK and RFK by some other sets of initials. But to go on about that is tiring, and that’s what they rely on: the long attrition, diminished returns on energy expended. Half of those bad boys are dead anyway and in hell, if there is one. The other half are drooling in hell’s waiting room.

The Ioway plates went to Tony Schwartz in New York. Not Tony Schwartz, the ghostwriter of the Trump Art of the Deal book, but Tony Schwartz, the sound genius who recorded a good deal of New York City, and taught at Fordham with his friend Marshall McCluhan.

This Tony wrote books like Media, the Second God, an eerily prescient volume, in 1981. I had connected with this great man at a time in my advertising career when I was exploring sound and words, and Schwartz had been responsible for some blockbuster commercials for Coca Cola and that chilling “Daisy” atomic bomb commercial, the LBJ campaign spot, not to mention hundreds of others. The photographer Edward Steichen called Tony Schwartz the man “who moved sound recording into the realm of the arts.”

Tony was also a talented designer and award-winning poster artist besides being a sound archivist. Or sound activist. The famed artist Ben Shahn told a friend, “Tell Tony, he’s my kind of artist, hard-boiled and beautiful!” And my kind of mentor.

But Tony, may he rest in peace, deserves an essay all his own. I was so proud to know him, and the Ioway plates were just one of many eclectic and quirky things that passed between us in the mail. When I sent them, I attached a note: New York, New York, or a village in Ioway, the only difference is the name…after the way Sinatra pronounced Iowa in “Lonely Town.” We communicated via tapes, phone calls and postcards. He passed away in 2008. Those license plates may still be somewhere in New York.

R.I.P. Ioway plates and all that they represented to me back then. And now.

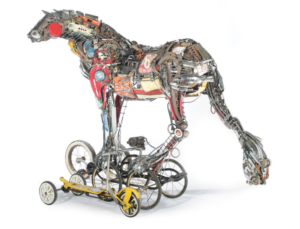

Photo of sculpture courtesy of author. For more information, click image for hyperlink.