The We Generation & Why We Must Consider the Stoics Now

For Nick and Clayton

Let’s begin with the idea that Me Generations exist. Further, since the end of the baby boom, there has been a common belief that subsequent generations were, in fact, Me Generations. Whether it was the find-yourself sixties or the find-your-passion millennials, the last fifty years have been marked by gazing inward.

It is a remarkable narrative: five decades that have been all about Me. Pursue your dreams. Find your true self. Assuming that this narrative is accurate, that we have been habitual navel-gazers, I’m here to say that the Me Generation is already dead. The time has come to pull your head up and look around.

There have been countless articles and essays written over the past decade on these self-centered generations, and there has also been plenty of blowback. Some would say that all generations are self-centered, and still others would say that such self-centered thinking is the right way to live, the natural and best way to be a fully realized person in the world. In other words, to find your way in the world you must include the ability to find yourself. Let’s hold onto that thought for now.

Here’s a brief excerpt from a 2013 article from Time Magazine called “Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation” that drops some surprising psychology statistics in the assertion of an egoistic state of affairs:

Here’s the cold, hard data: The incidence of narcissistic personality disorder is nearly three times as high for people in their 20s as for the generation that’s now 65 or older, according to the National Institutes of Health; 58% more college students scored higher on a narcissism scale in 2009 than in 1982.

You don’t have to search hard to find counter arguments to this me-centric proposition, but even these counter arguments seem to be laboring, swimming against currents that are strong and deep. But my point here is not to rehash the question of whether or not the last five decades have been marked by outsized selfishness. My intention is to look toward the future, and indeed into the present. What I want to say here is that regardless of the putative me-generations that have preceded this moment in time, we are doubtlessly facing the need to embrace a collective mindset, a cultural value system that revolves around the needs of the collective, and indeed the needs of the world itself. We are, I would say, doubtlessly moving toward a We Generation. And we are moving quickly.

Furthermore, I propose that we look back a thousand years or so and consider the Stoic Philosophers both individually and collectively. When Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 CE) says in Meditations 6.54 that “what injures the hive, injures the bee” we have a concise metaphor for how the Stoics viewed the world and the role of people in the world. Marcus was Emperor of Rome and is considered to be one of the prominent figures of the Stoic school, and he represents perhaps the culmination of the stoic movement. His Meditations outline and reinforce many of the key refrains of the Stoics, and they reflect his attempts to live them in a very real and dangerous world. Marcus was, after all, more than a philosopher. He was a ruler, a general, a politician, a father, and a husband.

Marcus is far from consistent, and at times he seems to be arguing openly with himself. His Meditations themselves seem to enact a method for finding his way. To the point, he articulates exactly the kind of Stoic ideas that we will revive in the We Generation. “What injures the hive, injures the bee.” The crucial theme here is the mutuality of the relationship between individuals, the community and the world. What is good for the world is good for the individual, and what is good for the individual is good for others. There is no division, so separation, between the three. The individual, the collective and the world are one.

What happens to you is for the good of the world. That would be enough right there. But if you look closely, you’ll generally notice something else as well: whatever happens to a single person is good for the others. (Good in the ordinary sense as the world defines it) [Meditations 6.5]

The Stoics, including Marcus, spend a great deal of time on the proper life of the individual (as an individual). In fact, the right behavior of the individual consumes considerably more paper than the relationship of the individual relative to the community. And yet the right individual behavior is inherently considered within the context of how that individual fits into the community. There is no right behavior without the community.

In fact, all of the Stoic thinkers spend a great deal of time and energy sorting through the right individual virtues. What does it mean to be a wise man? What is the essence of personal courage? What is the good? Or in the words of Diogenes Laertius, “the virtues – prudence, justice, courage, temperance, and the others – are good” (Stoic Reader, p. 117).

But what stands out most forcefully about Stoic ethics, and particularly in the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, is that the good of the individual is inseparable from the good of others, of the community, and both are mutually and inextricably tied to the good of the world.

And so why should we look back at the philosophies of the Stoics? Why now? Precisely because the Stoics articulate a living ethical philosophy that emphasizes the needs of the greater collective as well as the needs of the world. And increasingly we are collectively recognizing that we all must focus on the needs of the world, both as individuals and as a community of living beings.

And so then what are we to say about the needs of the world? Can we even begin to articulate a class of needs known as the needs of the world? Perhaps we can limit these needs to the needs of this world, the human world at this moment in time. Or even more precisely, the needs of human beings in this world.

The popular term “climate change” fails to encompass the situation in which we find ourselves. In my own view, the term “climate change” is a euphemism that barely even sidles up to the situation. Furthermore, climate change per se is merely an aspect of our challenge. Just one symptom. We have become the instruments of our own demise, and the demise of many other earthly beings. We the People have successfully grown to dominate the world in ways that could not have been imagined by Marcus and his like-minded contemporaries.

I see no reason to prevaricate here: the human race has reached a point where extinction has emerged on our horizon, and this threat has appeared as a result of business as usual. It is not the result of nuclear disaster, although that specter too remains with us. Simply by going about our lives, driving to work, visiting the market, heating our homes, farming our fields, growing our footprint, simply by doing the things that humans do, we have become an overwhelming force of destruction. I do not need to go into the evidence on the monumental challenges, since so many others have done this work already and continue to do so.

In The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert summarizes the situation in plain terms. In addition to classifying homo sapiens as a clear and proven “super killer” of other species, Kolbert paints a picture of where we go from here. “Right now, in the amazing moment that counts to us as the present, we are deciding, without quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open, and which will be closed forever. No other creature has ever managed this, and it will, unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy” (p. 268).

The world that the Stoics faced was also dangerous and threatening. Death was everywhere. Of Marcus’ 13 children, only one son and three daughters survived his own death. Could it be that an acute awareness of danger and risk drives us toward a philosophy that values the success of the collective? Perhaps. But it does not necessarily point us toward a better understanding of the health of the world, or a philosophy that grounds itself in nature as the ultimate source of what it is right and good, and it is this key connection that makes Stoic philosophy important now.

As Emperor of Rome, Marcus also saw his fair share of death and violence in warfare. He traveled on campaigns in the outer reaches of the empire to fight and surely witnessed gore and dismemberment. And he consistently turned to philosophy as a means to understand the world, but also as a way to know how to act in the world. And for this, Marcus learned from his teacher Epictetus. A freed slave, Epictetus developed his own school in Turkey and heavily influenced the ideas of his time as well as many classically trained thinkers that followed him. We see and hear the influence of Epictetus on Marcus clearly:

One cannot pursue one’s own highest good without at the same time necessarily promoting the good of others. A life based on narrow self-interest cannot be esteemed by any honorable measurement. Seeking the very best in ourselves means actively caring for the welfare of other human beings. Our human contract is not with the few people with whom our affairs are most immediately intertwined, nor to the prominent, rich, or well-educated, but to all our human brethren.

View yourself as a citizen of a worldwide community and act accordingly. (Epictetus, The Art of Living, p. 95)

Note here that awareness of our mutual interdependence is not enough. One must also act accordingly. Stoic ethics informs our conduct, and it is our collective conduct that leads to the overwhelming impacts of our collective action. Furthermore, we find that “true happiness is a verb. It’s the ongoing dynamic performance of worthy deeds (Ibid., p. 85)” and then “our life has usefulness to ourselves and to the people we touch (Ibid., p. 85).”

As I mentioned earlier, the Stoics spend a great deal of time and energy meditating on the importance of staying true to one’s self, to finding a kind of inner peace by avoiding the appearances of wealth or power or following the unreliable desires that drive us. “Keep your attention focused entirely on what is truly your own concern, and be clear that what belongs to others is their business and none of yours (Ibid., p. 4).”

Marcus instructs himself that “the others obey their own lead, follow their own impulses. Don’t be distracted. Keep walking. Follow your own nature and follow Nature – along the road they share (Meditations, 5.3).” There is a deep tension here between the need for self-possession and the need for duty to the community. In the end, these two ideas coexist in the Stoic mode. They are not mutually exclusive. You must live a life where you learn how to be true to your own individual nature, and yet you must also live a life where you exist as a part of the human community. They are deeply inclusive. And it is the world, and nature, that complete the picture of the fully realized Stoic life.

Let us return to Epictetus again here for a moment. He calls to us to “view yourself as a citizen of a worldwide community and act accordingly.” To me, this is the essence of the collective worldview that is upon us. Whether that is because we have found ourselves in a “worldwide community” simply by and through the success of humanity (as members of the dominant species called homo sapiens), or whether it is because multiculturalism is a force bigger than economic globalization and emergence of the internet. This is where we are now, and this is why the ideas of the Stoics apply deeply to the times that are ahead of us.

And so now let us focus on the Stoic idea of Nature, on the role of Nature in our time and on the ideas of the Stoic philosophers. This then is the true heart of the matter. We are born of Nature and we are with Nature as beings. We have our own nature, and we live in the natural world. We cannot escape Nature and at this moment in time it appears that Nature cannot escape us.

If so, then the reason that tells us what to do and what not to do is also shared.

And if so, we share a common law.

And thus, we are fellow citizens.

And fellow citizens of something.

In that case, our state must be the world. What other entity could all of humanity belong to? And from it – from this state that we share – come thought and reason and law.

Where else could they come from? The earth that composes me derives from earth, the water from some other element, the air from its own source, the heat and fire from theirs – since nothing comes from nothing, or returns to it. (Meditations, 4.4)

The air and the water, the earth that composes me, and the law. “Our state must be the world.” Indeed. Notice here that Marcus points us back to reason and law. He was an Emperor after all. He had to live and lead and legislate. He fought frontier battles, killed men and sent other men to their death. It is not enough to philosophize, but we must also act, and act according to a philosophy that recognizes Nature and the world. “What other entity could all of humanity belong to?” he asks us. How do we answer? How do we respond? We must respond by engaging our reason and by using the tools of “common law” to govern, to lead the way to a world in which “we are fellow citizens.”

We like to say, at least in the U.S., that we are a nation of laws. We boast and we pat ourselves on the back and say that we are the greatest nation on earth. And yet in the same breath, we also love to deride the role of government, of our own government. “Government is the problem,” as Mr. Reagan would have it. This self-serving contradiction must be overcome if we are to find a way forward. The rule of law must bend itself toward a Stoic ethic, and we must learn to follow (and mend) the laws we create. One gets the sense that we use these phrases (“rule of law” and “government is the problem”) primarily for their emotional impact without much interest in what they actually mean and how they inform our collective conduct.

Stoic philosophy is not limited only to ethics or how to live a good life. There is also a considerable body of Stoic thought that addresses what is traditionally classified as logic and physics. In this essay, I am primarily focused on the ethics, and an all-too-brief summary of logic and physics will have to suffice here. According to Inwood and Gerson, Stoic logic posits that “human beings can achieve genuine knowledge about the physical world” and that “this is the only world that exists” (Inwood and Gerson, p. xiii). And with regard to physics, they “rejected Platonic Forms and incorporeal gods, including Aristotle’s Unmoved Mover, and they denied that immanent forms should be thought of as opposed to body” (Inwood and Gerson, p. xiii). We certainly create categories to better understand the world, but we construct those categories based on the experience of the natural world, without which we do not exist.

While these brief summaries on Stoic logic and physics are certainly reductive, we can see nevertheless how their logic and physics relate to their ethics, their belief that nature provides us with the sources for the right way to live. We can in fact perceive the world, and we must understand the world if we are to live a successful life. For those who claim that we cannot know the world, this world, I would recommend that they might want to retire to a safe classroom for further studies in immaterial diversions.

Cicero too clearly falls in line with the Stoic ethical agenda. In On Goals, Cicero’s line of thought traces out a coterminous trajectory, “that the highest good is to live by making use of a knowledge of what happens naturally, selecting what is according to nature and rejecting what is contrary to nature, i.e. to live consistently and in agreement with nature” (Stoic Reader, p. 155). This reiteration of the Stoic creed then leads us forward to the idea of community. “From this it develops naturally that there is among human beings a common and natural affinity of people to each other, with the result that it is right for them to feel that other humans, just because they are humans, are not alien to them….[So] we are naturally suited to [living in] gatherings, groups, and states” (Stoic Reader, P. 157).

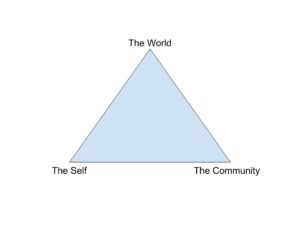

Ethics provides us with an inherently normative agenda. How we should live is at the core of the ethical project. And what we find with the Stoic ethical formulation is a triangle with three distinct points. On one corner of the triangle, we have the individual (i.e. the self); on the second corner we have the community (i.e. the polis); and on the third corner we have the world (i.e. nature). These three points connect to one another in a vital and foundational manner. If you take one of these corners away, the system falls apart. “This will be clearer to you if you remind yourself: I am a single limb (melos) of a larger body – a rational one” [Meditations, 7.13].

But when we consider where we are today, our relationship with the world in light of the impact of the Anthropocene, then I propose that this triangle represents the ethical formation of our time. Each point on the triangle is connected to the other point. We cannot effect change in the world without the community. The community is composed of individuals that are driven by purpose. It is through the community that we enact laws, wage wars, change the shape of history.

To what degree can we distinguish our individual values, individual ethics, from our collective values? Certainly we must internalize certain values within ourselves, we must take them in and comprehend what they mean. We come to embody these values in our actions, and more fully in our collective actions. As individuals, we struggle against them and we embrace them. We may even strike out on new territory to define a new set of values. Certainly we can see examples in the original thinkers, the individuals who have redefined how we see the world and the community. I’m thinking of individuals like Adam Smith or Karl Marx, like Charles Darwin or John Calvin. But we impact the world as a collective, and it is impact that we must consider now. An individual cannot raze a mountain in West Virginia, but a collective can. An individual cannot turn a forest into a farm, but a collective can.

Over generations, it is the collective that materially changes the face of the world with the force of its projects. If water was the main force of worldly change for millions of years, it is now human projects over hundreds of years. And so what we must do is to bend the force of the human collective, and bend it toward the future of the world. It will happen regardless, and so we must reinvent this relationship between the individual, the community and the world.

The World, this world, is now thoroughly entwined in the Anthropocene, the epoch of homo sapiens. This triangle becomes the true trinity, the modern ethical dilemma that we face. The trinity of 1. the individual with purpose, 2. the community with impact and 3. the world as that which makes it at all possible in the first place. Barring some new data, the world becomes the final sine qua non.

Let us not delude ourselves, however. The world will go on with or without human beings. It went on long before we got here and it will go on long after we are gone. To deny this fact is to deny the fact-based understanding we have of our world. But that does not mean that we have no duty in our present situation. In fact, survival in and of itself is a justification for a new collective philosophy, a philosophy that guides our ethics and thus our laws and our behavior. And beyond survival, we must pursue the ability to thrive; we can and must pursue Eudamonia (Greek word often translated as human flourishing).

Eudamonia as an overarching goal directs us toward the ability to thrive as human beings, but it can also direct us toward the ability to thrive as member of a community. Furthermore, Eudamonia can mean the ability of the greater community of human beings to thrive as a whole. And as we consider the ethics of this new Stoicism, an ethics that arises in the midst of an existential threat, I propose that the very idea of thriving as an individual must include the thriving of the collective, of the entire species.

Stoic ethics, and ethics in general, sees itself as “last in line” when compared to the other branches of philosophy, and that includes science. It is last because ethical judgments come after all the information is in. It waits for the best known science before it weighs in. As Lawrence Becker describes this in a contemporary assessment of the Stoics, “it is last because it cannot begin until all relevant description, representation, and prediction are in hand, all relevant possibilities are imagined, all relevant lessons from experience, history, practice are learned – until, that is, until all the empirical work is in” [A New Stoicism, p. 9]. And the science that’s coming in now tells us that the Anthropocene is hard upon us. The success of human beings has imperiled the living world as we know it, the world at least as it can be defined between the birth of humans and the present day. In other words, the world that gave birth to humankind and will survive it one way or another.

This is no epistemology, no metaphysics, no mathematics. This is about how to live the right life, the just life, the life of the logos. This is about individual conduct and collective conduct. Less and less do we have time and space for the luxury of epistemological engagements. It might even be considered indulgent at this point. When we are standing on the train tracks (side by side with our children in tow), it is pure negligence to spend time discussing the subtle distinctions of how we know for sure that the train is headed our way. We can see light, feel the rumbling and hear the engines. That is enough.

This ethical system, this trinity, reveals the existential relationship between three now primordial points: the individual, the community, and the world. They are visible to us in their connected state, in their existential ontology. Now more than ever, in this evolutionary moment we face, the Stoic triangle provides perhaps the only formulation that simply and reliably shows us the path forward. For it is only through the purpose, indeed the behavior, of individuals and the communities that we will prevail, if we are to prevail at all. No alien being is coming to save us. Only we can save ourselves.

Regardless of your stance on climate change or the nature of the Anthropocene, even if you choose to ignore the science and follow your faith or your hope, the data and these ideas are here and they are not going away. The We Generation is arriving today. We will learn to find our pleasure not solely in the pursuit of our own personal pleasures but in the success, indeed the survival, of the community within the world as we know it.

And our contemporary conception of the community will expand and develop. It must change. In fact it is already changing. We can see the organic food movement and the free range movement as examples of our already expanding the idea of community. If our community can include dogs and cats, which it does, then it can contain other living creatures, and indeed all living creatures. The community does not have to remain limited to the community of human beings, as it did with the Stoics, but it can include the living beings of the entire community of the world.

Finally, what will be required will be an invigorated and creative We Generation, and in fact many We Generations. We will need the collective imagination and commitment to reinvent our ways of living and to find personal pleasure in that work. We will need to consider the words of an individual, of Epictetus, and we will need to take considered collective action:

Take charge of your thinking.

Rouse yourself from the daze of unexamined habit.

Popular perceptions, values, and ways of doing things are rarely the wisest. Many pervasive beliefs would not pass appropriate tests of rationality. Conventional thinking – its means and ends – is essentially uncreative and uninteresting. Its job is to preserve the status quo for overly self-defended individuals and institutions. [Art of Living, p. 92]