The age-old pattern of Human-Centered Design and the emergence of World-Centered Design.

Introduction

After considerable reflection, it seems clear to me that there is nothing humanity admires more than itself. The very word humanity carries with it a generous payload of admiration and goodness. It is a gift we have bestowed upon ourselves. We employ the word “humane” to inculcate generations with the notion that humanity is “marked by compassion, sympathy, or consideration.” When we say humanity, in other words, we don’t mean “marked by avarice, ambition, or destructiveness.” We admire the creativity, intelligence and talents of humanity, and we institutionalize our admiration through a canon of studies we call “the humanities.” But where our love for ourselves makes its greatest impression is in our capacity to make new things that exist in the world. We furiously make things for ourselves, often as tributes to our greatness. We are stunningly industrious. And chief among our many talents, we are master inventors and diligent makers. When we look out at the world, whether from an airplane or from a street corner, what we see is that we are tireless Designers.

In a recent essay entitled “Ideas in the Sky,” Ben Taub profiles the author and journalist, Jonathan Ledgard. Using Ledgard as a living vessel of a hopeful vision of the future, the piece explores his ideations and adventures related to the planet’s future. Ledgard travels fluidly between Davos and Rwanda looking for transformative answers. In short, according to Ledgard, “the world [is] undergoing an accelerated convergence of technological and environmental trends.” It’s a tidy sentence. Ledgard is what we might call a practical futurist on a mission to help save humanity from itself. “The only possible thing to do,” says Ledgard, “is to go in an imaginative direction.” Futurism, it would seem, has become more and more of an everyday activity. Deeper into the essay, one of Ledgard’s cohorts speaks briefly of “architecture” and wants to know how it can play a role. It seems like an odd question, given the essay’s theme of “saving the world,” and then some unnamed person mysteriously says, “Design is the problem.” Design indeed. While architecture figures somewhere in questions about our future, the question of Design will determine the outcome.

Win or lose, we are all Designers now. Over the last several decades, I have watched as the field of Design has evolved and become increasingly prominent. My task in this essay is to examine the field of Design, and in particular the discipline known as Human-Centered Design (HCD). Humanity, as already noted, loves to find itself in the center. Furthermore, I reconsider Design as the human force for collective creation and destruction. The practice of Design is where the battle for the future will be fought.

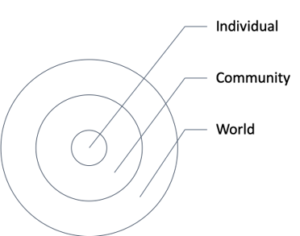

I wish to elevate the practice of Design and to dismantle it. While “Human-Centered Design” has emerged as one of the most influential and admired disciplines in the Design field, it is in fact the most dangerous. As I have come to learn more and more about Human-Centered Design, my simple observation is that Human-Centered Design is all we have ever had, and it is what has gotten us into trouble. I reject the sanctified faith in Human-Centered Design and the idea that it provides Designers with a novel and beneficial method. It is, rather, a grotesque fallacy disguised as a useful toolbox. Nearly everything we design is for the benefit of humanity, and that fact has dealt us a hand of existential perils. Humanity has always stood stubbornly in the center of Design.

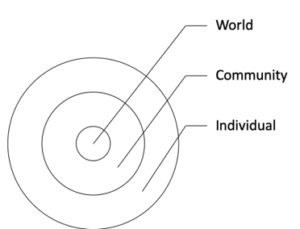

What we need now is to place a new vision at the center of Design. We require an entirely new Method. We must follow the model of Francis Bacon who, precisely 400 years ago, sets out in The Novum Organum to “reject ways of thinking” of his time and chooses instead to create a new method. “We are left with only one way to health—namely to start the work of the mind all over again” (book 1). We must reject, furthermore, the Design Methods we have been handed. We must rip out the idea of Human-Centered Design and we must replace it with World-Centered Design (WCD). The time has arrived to move the needs of humanity out of the center of our design methods. Humanity has won. We have, as commanded by scripture, obtained dominion over the earth. This is not to say that the needs of humanity no longer matter, and it does not predicate the need for a system build on misanthropy. We no longer have time for the luxury of misanthropy. Perversely, humanity matters more than ever. It is humanity, after all, that must reconceive its capacity for Design, the ability to make new things in the world, towards an imaginative direction. As Ledgard says, “imagination at scale is our only recourse.”

What is Human-Centered Design?

One of the first uses of the term “Human-Centered Design” was by Mike Cooley in 1980 in a book entitled Architect or Bee.  Since that time Human-Centered Design has grown to become one of the central disciplines of Design worldwide, especially as it relates to product and service design. The practice of Human-Centered Design goes by the shorthand HCD. The fast maturing discipline of Design, and HCD in particular, has moved steadily into the core of business strategy. More and more, HCD determines how we make products and services. HCD shapes how we make critical decisions on what to build and how to build it. It also includes the design of complex systems and consumer experiences. In short, as Norman points out in The Design of Everyday Things, “all artificial things are designed” (Norman, p. 4). When global strategy giants like

Since that time Human-Centered Design has grown to become one of the central disciplines of Design worldwide, especially as it relates to product and service design. The practice of Human-Centered Design goes by the shorthand HCD. The fast maturing discipline of Design, and HCD in particular, has moved steadily into the core of business strategy. More and more, HCD determines how we make products and services. HCD shapes how we make critical decisions on what to build and how to build it. It also includes the design of complex systems and consumer experiences. In short, as Norman points out in The Design of Everyday Things, “all artificial things are designed” (Norman, p. 4). When global strategy giants like  McKinsey[1] are buying Design companies, such as the 2015 acquisition of Lunar, we can observe the steady trend of Design’s rise to primacy. HCD has moved to the heart of that Design primacy. The elevation of Design as a discipline is not difficult to justify. Simply stated, innovation drives modern business, and Design Thinking has become an essential discipline for driving innovation. Furthermore, the process of investment and development in the modern world begins with the discipline of Design, and HCD predominates. Designers create the frame for nearly everything we build.

McKinsey[1] are buying Design companies, such as the 2015 acquisition of Lunar, we can observe the steady trend of Design’s rise to primacy. HCD has moved to the heart of that Design primacy. The elevation of Design as a discipline is not difficult to justify. Simply stated, innovation drives modern business, and Design Thinking has become an essential discipline for driving innovation. Furthermore, the process of investment and development in the modern world begins with the discipline of Design, and HCD predominates. Designers create the frame for nearly everything we build.

Genesis 1.26: “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

HCD proposes that the key to building products, services and systems requires that Designers place the needs of humans in the center of the design method. There is, however, a treacherous fallacy in the emergence of HCD. HCD will often pass itself off as an innovation in thought and in method. The unacknowledged and unstated modus operandi, however, of HCD is that humans have always been in the center of what we see and what we make. There is nothing new here. Human-Centeredness secretly impels our creation mythology. In the Judeo-Christian worldview, anthropocentrism actuates the books, chapters and verses. In our most successful creation stories, humans occupy the center of the world. In the scriptures, God made the world, put us there and then made us the custodians. When we look out at the world, we are told, we should see a place that was made for us. We should see the world as the pliable domain of our livelihood and our dominion, the malleable garden we were put here to tend for our own purposes.

The colonial period systematically spread these anthropocentric religious beliefs as far as could be imagined, literally to the ends of the earth. And even in those expansions, we see that humans were already shaping their world. And with the rise of market-based economics and the parallel emergence of scientific methods, humans have only strengthened their grip on the center. Our tools and methods have grown more powerful and more impactful. We are, in short, at the center of everything. And so we can observe further that the practices and behaviors of something we call Design are fraught with profound difficulties. These problems run deep. Our formative idea of the very existence of the world, for example, seems to require a creator, a great Designer.

Genesis 1.27: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.”

HCD has asserted itself in the formal standards that define and govern our institutional practices. The International Standards Organization (ISO) has a documented chapter devoted to the HCD method:

“Human-Centred Design is an approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems usable and useful by focusing on the users, their needs and requirements, and by applying human factors/ergonomics, usability knowledge, and techniques. This approach enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility and sustainability; and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety and performance.” ISO 9241-210:2010(E).

What stands out in the crystal clear and institutionalizing language of the ISO standard is not what it stipulates about Human-Centered Design, but what it does not stipulate. There is no mention of impacts of Design on the world.

As humanity asserts itself as the custodian of the world, as the maker of the products, services and complex systems that shape the world, these Human-Centered ideas must give way to a world-centric system. The core mission and purpose of Design must change, and it must change today. The anthropocentric first principles we live by today must give way to world-centric first principles. I will not recapitulate the reasons here, and say only that the case for changes toward World-Centric methods has already been made by writers like Elizabeth Kolbert, Naomi Klein, and many others. As I have said in other places, the case is closed. The Anthropocene is upon us.

So now what? The first principles and techniques that guide how we frame and build products, services and complex systems, must take humanity out of the center of Design and move toward a set of assumptions and standard practices that start with World. What we require, in short, is a shift toward a method that we can call World-Centered Design (WCD). This will require a radical shift in how Design in conceived, taught and practiced. It will impact the most powerful institutions in the world.

Human-Centered Design World-Centered Design

Cooley and Machines

Writing in the 1980’s, Mike Cooley focuses his attention squarely on the dehumanizing impacts of human-machine interactions. He witnesses the invention of Computer Aided Design (CAD) and examines the impacts on his world as a technical designer. He sees an emerging situation where the rise of machinery and automation are robbing workers of their knowledge and their value. A person’s bargaining power “has been absorbed and objectivised into the machine through the intervention of the computer and is now the property of the employer, so the employer now appropriates part of the worker and not just the surplus value of the product” (Architect or Bee, p. 21). Cooley sees the worker, and the Designer in particular, as a creative force that cannot be reduced to another impersonalized piece of the machinery of the business. He is deeply concerned about the well-being of the worker. Work should be satisfying and rewarding, and automation is a threat to that worldview.

Genesis 1.28: “And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

Cooley traces the disconnection of manual skills from creative and intellectual skills over time. Machinery and automation have steadily displaced manual skills and relegated them to a lower status. This separation of creative and intellectual skills from manual skills signals a loss of creativity and meaningful work experience. He warns the reader about “a growing separation of theory and practice, a growing emphasis on the written ‘theoretical forms of knowledge’ and, in my view, a growing confusion in Western society between linguistic ability and intelligence (in which the former is taken to represent the latter)” (p. 60). These gaps have been emerging for centuries, and the invention of computer aided design systems accelerates the gaps between theory and practice. Those who know the theory may have little or no knowledge of the practice. While this trend may work to the detriment of the Designer, it works to the benefit of the capitalist who looks to exploit labor for the sake of profit.

While the preponderance of Bee or Architect examines the plight of workers, both skilled and unskilled, Cooley also sees the power of Design as a distinct discipline. The ability to create and define a set of practices can lead to a reduction in uncertainty. But this kind of normative power acts as a sword that cuts both ways. “Furthermore, we begin to regard design as something that reduces or eliminates uncertainty, and since human judgment, as distinct from calculation, is itself held to constitute an uncertainty, it follows some kind of Jesuitical logic that good design is about eliminating judgment and intuition. Furthermore, by rendering explicit the ‘secrets’ of the craft, we prepare the basis for a rules-based system.” This idea of the rules-based system, as we shall discover, reflects the machinery that has guided us to many of the problems of our time, but also forms the basis for a way to solve them. What are these rules and how do they get written? This is the critical reversal we must make. Design systems, driven by a method, are both the source of our troubles and the path out of our troubles. There is no going back. What we must do, then, is to change the rules of the system.

Why Design Matters

Why is it then that Design is such an important topic for consideration and examination? Why at this moment in time should we consider the Design activity? Put simply, Design is the discipline (behavior) that most impacts the worldly problems we solve. Design, in other words, represents the human faculty to shape the world around us. The Designer is the first on the scene, sketchbook in hand, irrespective of whether or not the Designers even consider themselves to be Designers. In order to further examine the inner workings of the Design activity, we can propose that the Designer performs two crucial and complementary activities, both of which require our consideration. First, the Designer “creates the frame” and then the Designer “imagines the object.” It is a two-step move.

Genesis 5.1: “This is the book of the generations of Adam. In the day that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him;”

By “creating the frame,” the Design activity defines the problem at hand and thus creates the boundary for the resulting design. The act of boundary definition requires our utmost attention, because it is the Designer who animates the first principles of Design and thus creates the frame. These framing Design activities, therefore, articulate and illustrate the design problem, and they imagine how the problem might be addressed. When we are performing as a Designer, we are bringing ourselves fully to bear on what we face. We bring our senses, our education, our values, our goals, our ideas, our experiences, our intelligence, our assumptions, our emotions, our selves. We bring ourselves to the process of Design in order to see the world as it is and to imagine how it might be different, to consider how to make something happen, how we make something new in the world, something that will exist independently of the Designer, something that will perhaps live beyond ourselves.

The Designer’s role is not merely to “create the frame.” The Designer must then take the next step of imagining the object that does not yet exist. The Designer draws a sketch of an altered landscape and, if the process is successful, everything that follows is forever different. In this movement the Designer has already begun to leap into a future that does not exist yet. The new something may be an object or a process or an experience, but the situation is the same in all cases. The Designer imagines what can emerge next and must eventually make the case for why it should be one way or another. The Designer considers why it should be this way and not that way. The Designer of the hydroelectric power plant, for example, must decide how to make affordances for the creatures that live in the river. As the power plant is designed, the Designer will “imagine the object” that will alter the landscape in profound and lasting ways. This is why “the frame” is so crucial. When the Designer “creates the frame,” the problems are expressed, explicitly or implicitly, so that the imagined object can be shaped accordingly. This method should be seen as an iterative and recursive process.

Certainly the Designer must incorporate other agents and forces in the process. These forces are manifest typically through other participants, such as the structural engineers and capital investors and business stakeholders and governmental representatives. The job of the Designer, nevertheless, is to imagine the new state of the world. Perhaps more to the point, we must stipulate unambiguously that all of the participants mentioned above are actors in the Design process and are in fact acting as Designers. They all conspire to “create the frame” and to “imagine the object.” The Design activity implicates everyone who plays a part in shaping and approving the final design. In almost every case, Design should be understood as a collective process.

Quran 2.21: “O mankind! Worship your Lord (Allah), Who created you and those who were before you so that you may become Al-Muttaqun (the pious – see V.2:2).

Let’s put this into proper perspective. This is how cities are born in the sand, how dams are built in canyons to capture the water, how power plants are erected to provide the electricity, how the streets are arranged to make way for the automobiles, and so on. It is how a farm will suddenly appear on the other side of the river on a strip of land that was recently a forest. It is how a building is wired with copper, how the floors are pile carpeted, how the walls are painted, how the trash is collected, how the water runs through the pipes. It is how a drug is made, how a bridge is built, how a piece of software will enrapture the mind of a small child. The time has come for the discipline of Design to come to terms with itself.

As Designers, we have been shaping the world in ways that suit our needs far longer than we may realize. Environmental Design is as old as we are.  In 1491 by Charles Mann, a history of the Americas prior to Columbus, the author opens the book by pointing out that the Native Americans shaped their landscape so deeply that the signs of their alterations are still clearly identifiable in the landscape in the 21st century. Contemporary researchers have identified native impact on the land and can trace the alterations back to civilizations that no longer exist. “Indians were [in the Western Hemisphere] far longer than previously thought, these researchers believe, and in much greater numbers. And they were so successful at imposing their will on the landscape that in 1492 Columbus set foot in a hemisphere thoroughly marked by humankind (p. 4).” In The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes, a history of the founding of Australia, we discover the same evidence that humans will radically alter their landscape to suit their needs. “The crude aboriginal technology did wreak changes on the landscape and fauna, for it included fire. Everywhere the tribes went, they carried firesticks and burned many square miles of bushland” (p. 13).

In 1491 by Charles Mann, a history of the Americas prior to Columbus, the author opens the book by pointing out that the Native Americans shaped their landscape so deeply that the signs of their alterations are still clearly identifiable in the landscape in the 21st century. Contemporary researchers have identified native impact on the land and can trace the alterations back to civilizations that no longer exist. “Indians were [in the Western Hemisphere] far longer than previously thought, these researchers believe, and in much greater numbers. And they were so successful at imposing their will on the landscape that in 1492 Columbus set foot in a hemisphere thoroughly marked by humankind (p. 4).” In The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes, a history of the founding of Australia, we discover the same evidence that humans will radically alter their landscape to suit their needs. “The crude aboriginal technology did wreak changes on the landscape and fauna, for it included fire. Everywhere the tribes went, they carried firesticks and burned many square miles of bushland” (p. 13).  Design is not a modern invention, nor is it a discipline of a mechanized western economy. We clear forests, we redirect rivers, we trap waters, we change the composition of the soil, we raze mountains. We do this not merely by living on the earth, but with our minds, our hands and our tools. We do this with our ability to imagine a different design for the world. These skills do not stop at the everyday objects we see in our environments. We Design organism genetics, cancer therapies and quantum computing techniques. Humans are world shapers by nature, and we have accelerated the pace of change through our genius for Design.

Design is not a modern invention, nor is it a discipline of a mechanized western economy. We clear forests, we redirect rivers, we trap waters, we change the composition of the soil, we raze mountains. We do this not merely by living on the earth, but with our minds, our hands and our tools. We do this with our ability to imagine a different design for the world. These skills do not stop at the everyday objects we see in our environments. We Design organism genetics, cancer therapies and quantum computing techniques. Humans are world shapers by nature, and we have accelerated the pace of change through our genius for Design.

Cooley and Human-Centered Design

Toward the end of Architect or Bee, Cooley stipulates specific proposals for how Design should become human-centered. In chapter 8, he shifts away from a withering critique of capital-centric design principles and toward a practical set of recommendations. Using the Lucas Worker’s Plan as the foundation for his proposal, he offers a cookbook approach to practical strategies. For example, he proposes that “technology can evolve in a direction that includes the skill and initiative of workers, who make it more productive and evolve new skills appropriate to the new kinds of technology” (p. 152). There are several lists of these kinds of recommendations. But the key point here is that Cooley remains squarely focused on the needs of workers, and he argues for how the skilled worker will improve any technology-driven process because of their ability to think creatively and dynamically. There are a few brief moments in the book where Cooley turns his attention to socially beneficial efforts and environmentally beneficial projects, but the human worker is his mission.

He takes the formulation further by talking not just about Human-Centered Design, but what he calls human-centered systems. It’s not that humans stand in the center of the Design strategy, but that the systems we design, the production-grade systems that drive how we operate in an increasingly technology driven world, those systems should have humans designed into the center of their operations. “The product and processes should be such that they can be controlled by humans rather than the reverse” (p.155). Once again, Cooley wants to tilt the process of design so that humans remain in the center. On the surface, his strategy seems beneficial enough. He uses the argument that humans make those systems more effective and efficient, but his main purpose remains the value to the workers rather than the holders of capital. “The product and processes should be regarded as important more in respect of their use value than their exchange value” (p.155). The well-being of the people, the value-in-use, is what matters most.

By putting the worker in the center of his Design philosophy, he reinforces primordial anthropocentric tendencies. He simply places a different set of people, the workers, in the center of his Design system. The glaring problem with Cooley’s HCD is the lack of attention to that which is created. What precisely are these Human-Centered Design systems making? What is the impact of the outputs? Cooley’s central argument is one of economic power, or class rank, rather than a question of worldly impact, and thus the success of Human-Centered Design inadvertently reinforces the anthropocentric nature of our design strategies. What we must do is invert this system and put World impact in the center. The shift to a world-centric Design philosophy does not come at the cost of the individual or the community. Rather, a world-centric strategy relieves the individual and the community from endless pursuits of meaningless and destructive Design strategies. Furthermore, it will preserve the natural things that make our world what it is.

Don Norman and Human Psychology

Don Norman’s book, The Design of Everyday Things, was originally called The Psychology of Everyday Things. The shift from Psychology to Design in the title reflects the nearly interchangeable relationship between the needs and desires of humans and the goals of Design. Norman’s book is a staple in nearly every Design department in colleges and universities. After a brief discussion in the opening pages of the 2013 edition, Norman discussed the function of a particular door, and then he makes his first critical claim about Design principles. “Two of the most important characteristics of good design are discoverability and understanding.” Both of these two “most important” characteristics are about the experience from the perspective of the human. Absent, once again, in these two characteristics are the impact on the world. Perhaps this is due to the fact that Norman is focused on doors in a building, which is already a human-centered environment, but that is the Design setting he chooses to begin with: a human-centered environment. He has already created the frame.

Don Norman’s book, The Design of Everyday Things, was originally called The Psychology of Everyday Things. The shift from Psychology to Design in the title reflects the nearly interchangeable relationship between the needs and desires of humans and the goals of Design. Norman’s book is a staple in nearly every Design department in colleges and universities. After a brief discussion in the opening pages of the 2013 edition, Norman discussed the function of a particular door, and then he makes his first critical claim about Design principles. “Two of the most important characteristics of good design are discoverability and understanding.” Both of these two “most important” characteristics are about the experience from the perspective of the human. Absent, once again, in these two characteristics are the impact on the world. Perhaps this is due to the fact that Norman is focused on doors in a building, which is already a human-centered environment, but that is the Design setting he chooses to begin with: a human-centered environment. He has already created the frame.

Quran 2.22: “Who has made the earth a resting place for you, and the sky as a canopy, and sent down water (rain) from the sky and brought forth therewith fruits as a provision for you. Then do not set up rivals unto Allah (in worship) while you know (that He Alone has the right to be worshipped).”

Norman is openly focused on “everyday things” even though he dips into discussions of complex systems like nuclear power plants. He outlines a systematic approach and a language of terms and concepts to enable the Designer and to guide the Design process. Norman’s language includes concepts like affordances, signifiers, feedback and conceptual models. This is a comprehensive system and design method. And it reinforces the core concept of Human-Centered Design. After acknowledging that challenges are ever present, Norman claims that, “The solution is Human Centered Design (HCD), an approach that puts human needs, capabilities and behaviors first, then designs to accommodate those needs, capabilities, and ways of behaving” (p. 8). Make no mistake, Norman outlines a powerful system for guiding the Design of human-machine interaction (HMI) and he anticipates unexpected factors like errors and mistakes. These methods and tools are powerful, and could be used to support a World-Centric Design model, but they once again define the bull’s eye as fully and totally anthropocentric.

In Norman’s view of the contemporary world, “great Designers produce pleasurable experiences” (p. 10). This is the status quo for design today, and successful Design efforts lead directly to financially successful commercial products. When we create pleasurable experiences, consumers buy more products, and then those consumers encourage others to do the same. Successful products become viral, and viral products become financially rewarding to the investors. Such is the state of how we define successful Design. The Designers and their investors accumulate wealth and influence. In the World-Centered Design method proposed in this paper, we propose a different definition: “great Designers create important products that coexist with the world.” This new definition does not obviate the market goal of commercial success, nor does it exclude the need for financial success. Rather it pulls the human out of the center and places the Designer in the role of responsible custodian. While the idea of custodianship may make many Designers uncomfortable, it must be noted that Designers already have that role. As Designers, we simply haven’t come to terms with that fact.

The Problem with Human-Centered Design (HCD)

Human-Centered Design, as expressed by Cooley, provides new ways to combat the hierarchically-organized and capital-oriented power structures. These power structures make the Designer subservient to the needs of external capital. Human-Centered Design as expressed by Norman, provides a system for creating commercially successful products and experiences. The problem with these strategies is that we have been human-centered from the beginning. Human-centeredness is built-in. It is profoundly intractable. Furthermore, the evolution of capital-centric social structures creates a system whereby some people (the winners) are elevated in their status vis-a-vis other people, but it remains utterly human-centric.

Those people residing at the top, those with the capital to set the agenda and make the decisions, are putting themselves in the center of the center of the entire human enterprise. They are the most centric. The distinction between “at the top” or “in the center” is perhaps important, but for my purposes it’s not as important as the fact that capital-oriented systems are already human-centric. To say that our enemy is capital, and that our problems are themselves due to capital-centric systems, is to ignore that we invented capital in the first place. Capital is something we designed ourselves. Furthermore, and perhaps more insidiously, these capital-based systems have been able to effectively use the human-centric methods to further develop their capital position. The Human-Centered Design methods have evolved into powerful instruments to drive more productive consumerist cultures. The human consumer is the ultimate center of the Human-Centered Design method, and it is the Designer who put them there.

In the plainest terms, we can observe a two-fold problem deep within the Human-Centered Design method. On one hand, it reinforces the position of humanity at the center of everything, and on the other hand, it provides more powerful techniques to further develop that privileged position. This two-fold flaw fuels the machine that alters the world. When we pick up our tools and engage our imaginations, we have put ourselves in the middle of it all. The World becomes a palette of materials for our needs, and we shape it accordingly. The problem is not capitalism, although it certainly acts as a force to concentrate our tendencies. Capitalism is a second order problem. The first order problem is how humans engage with the world.

Cooley’s Marxist critique of the capital-centric system and methods is both accurate and disruptive to the time. But he misses the mark for the simple reason that he is exclusively concerned about people. He witnessed the deskilling and devaluing of both skilled and unskilled workers through the deployment of technology, technology that was conceived in a way that made the human obsolete. He was, of course, correct in his observation. But what he fails to see, simply due to the scope of his project, is that he inadvertently reinforces the central challenge that we now face. Human-centeredness prefigures nearly everything we imagine. Furthermore, after railing on the human obsession with efficiency that leads to dehumanized labor conditions, Cooley reinforces the premium on efficiency, only with the worker back in the driver’s seat. “The human-centered concept is based on the premise that a computer-integrated manufacturing system will be more efficient, more economical, and more flexible if designed to be run by a human than a comparable unmanned system” (p. 149). The purpose here is not to vilify Cooley. Rather the purpose is to understand how even the so-called radicals who drive change are still caught in the human-centered worldview. By attempting to dismantle a broken system, Cooley inadvertently repeats the problem more clearly. He aids and abets the human-centered power brokers.

Necessary but not Sufficient

It is perhaps a true statement that in our market-based economy, it is necessary for a business (or an individual) to achieve financial success through successful Design efforts in order to thrive in the world. But we can also say that while financial success is necessary, it is not sufficient. It is necessary because financial success reflects market success, and the financial rewards of that market success enable those organizations (or individuals) to pursue their goals and objectives. But in a World-Centric Design system, Design efforts must achieve more than financial success: they must also meet certain primordial and sustainable world-centric criteria. These two criteria (profitability and world-centeredness) need not be mutually exclusive. Furthermore, they must not be. As we continue to push the limits of sustainability, these two criteria will become part and parcel. There is no alternative path to take.

Too many Design efforts do not fully consider the impacts on the world around them, whether positive, negative or neutral. We need to establish new, simple Design criteria that accompany any project that includes Design activity or a Design method. There are basic, measurable questions that should be asked and answered. These design Criteria should not be considered merely as regulatory compliance hurdles, but rather they should represent a shift in the first principles of the Design system. These criteria form the basis for a new frame. A more thorough effort should follow from the following Design related questions, but they should be as brief, simple and clear as possible.

- Can we articulate how the proposed Design impacts the world, both in terms of inputs and outputs?

- Can we publish transparent criteria and quantifiable measures for world-centered impact?

- If we are unable to publish transparent criteria for world-centered impact, can we articulate the rationale for the departure that is based in a world-centered framework?

- Does the proposed Design expand or shrink the human footprint on the environment?

Judeo-Christianity & Anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism means quite literally human-centered. The roots of Anthropocentrism are clearly articulated in the religious texts of Judeo-Christian origin stories. In an essay by Lynn White, he states plainly that “Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has ever seen” (p. 2). Let there be no doubt about our shared human-centered mythologies. It’s not merely religion. The fields of anthropology and psychology, both heavy influences on Design principles, represent nothing more than the obsessive study of human behavior, history and civilization. It seems clear that these fields will now become critical to the project of world-centered design.

The Judeo-Christian tradition, including but not limited to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, tells us plainly that the world was put here for humans. White goes on to point out that Christianity “insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends” (p. 2). The first books of the King James Bible and the Noble Quran provide the religious foundations of our human-centered mythology. There is no subtlety here. There is instead the proclamation to “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that

The Judeo-Christian tradition, including but not limited to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, tells us plainly that the world was put here for humans. White goes on to point out that Christianity “insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends” (p. 2). The first books of the King James Bible and the Noble Quran provide the religious foundations of our human-centered mythology. There is no subtlety here. There is instead the proclamation to “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” Like true believers, we have, it appears, succeeded at this proclamation, succeeded beyond our most fantastic dreams, and we have succeeded to a degree that requires both a reckoning and a fundamental transformation. We must transform our philosophy, our mission and our approach to Designing the world around us.

creepeth upon the earth.” Like true believers, we have, it appears, succeeded at this proclamation, succeeded beyond our most fantastic dreams, and we have succeeded to a degree that requires both a reckoning and a fundamental transformation. We must transform our philosophy, our mission and our approach to Designing the world around us.

This paper does not attempt to make the case for the environmental crisis. This paper, furthermore, is not an attempt to convince anyone of the state of environmental decline. The Anthropocene wears heavily upon the world. The fact of it hangs over us like a dark spectre, and it haunts our daily actions. It challenges our understanding of humanity. This paper, rather, outlines a baseline for the first principles of Design as a world-centered practice. What matters now is how we reimagine our role in the world and our responsibility as Designers.

Quran 2.29: “He it is Who created for you all that is on earth. Then He Istawa (rose over) towards the heaven and made them seven heavens and He is the All-Knower of everything.”

[1] McKinsey engages global business and governments in global projects in industries such as Advanced Electronics, Aerospace & Defense, Agriculture, Automotive & Assembly, Capital Projects & Infrastructure, Chemicals, Consumer Packaged Goods, Electric Power & Natural Gas, Financial Services, Healthcare Systems & Services, High Tech, Media & Entertainment, Metals & Mining, Oil & Gas, Paper & Forest Products, Pharmaceuticals & Medical Products, Private Equity & Principal Investors, Public Sector, Retail, Semiconductors, Social Sector, Telecommunications,Travel, Transport & Logistics