Five years ago, in late November, I walked past a blossoming Tent City in the greenspace abutting the court buildings in Victoria, B.C. Each day, a couple more tents were pitched. I saw residents raking and bagging leaves to maintain a clean space. Daily, they sat on the ground in circles, talking. I stopped at Christ Church Cathedral across the street, where a parishioner who gave tours said, “I know they need a place to live, but not there. I wish they’d go.”

I poked around and learned that, for nearly a decade, Victoria’s homeless had formed tent cities on public ground and battled with courts and police for the right to pitch tents. They scored a major victory in 2009 when the B.C. Supreme Court upheld a decision that, if sufficient shelter space was unavailable, the homeless may camp on Victoria’s public lands from 7 p.m. (8 p.m. in DST) to 7 a.m. Subsequently, police and by-laws officers assumed the task of jostling homeless from slumber and yanking tents from moorings so the homeless would be out by 7 a.m. pronto.

In summer 2015, Victoria began exploring the feasibility of creating a permanent tent city for the homeless in one city park, where homeless would not be required to remove tents during daylight hours. Quickly, organized opposition coalesced around Mad as Hell Victoria, led ironically by a human rights attorney, and Stop the Tent City. Three months later, the tent city abutting B.C.’s courthouse began to form. Because it occupied provincial rather than city land, the homeless could legally tent 24/7 without being evicted and exposed to the elements.

After nearly a week of walking by, one brilliantly sunny December morning, I walked into the center of their greenspace. That seemed to operate like a key. All around, people emerged from their tents, talked with their neighbors, cooked and shared food, rake leaves, re-staked their tents, folded bedrolls, talked on cells, tied down bikes, or got themselves ready to leave the campsite to work, pray, play, or wander into town. The tent city’s residents were more diverse than I believed, roughly 40 percent female and half under 35.

I nearly stumbled over a woman in her late 20s, whose “Hi there!” woke me up. I asked, “Why is the tent city here? Who chooses to live here and why? What’re the other options?”

“Lots of homeless hate living in shelters, even if there’s space,” Jane answered. “Shelters have so many rules. Some people who work there try to make life harder. The worst is, after you’re settled, they kick you back out before taking you back, even if you’re medically fragile. Shelters aren’t safe, especially for women. It’s safer here. And its ours.”

I asked, “What do you want?”

She smiled, “A place I can call my own, where the sun comes streaming in. And a dog to take on walks.”

I asked, “Does the tent city have a defined leadership structure?”

“Hardly defined,” she laughed. “Someone handles PR. Margaret handles the protest.”

I was handed off to a 45-year-old man who was tying down a tent. I asked, “What kind of support are you getting from the surrounding community?”

“Some sympathetic people spend a night or two. There’re law students helping out. And donations, we get all sorts. I’m Mark, by the way.”

“What’s going on with the people I see every morning sitting in a circle?”

“We have an all-hands-meeting every day at 10, rain or shine. Some people call them talking circles. If people have a dispute, that’s where things get worked out.”

“Would you say the tent city is self-governing?” I asked.

“I’d call it self-management. You’re welcome to join our talking circles any time or just observe. You’re welcome to pitch a tent too.” There it was. I was being asked to join them.

I returned an hour later and found Mark at his personal campsite, littered with parts, the tent city’s makeshift repair shop. He told me Margaret was in the law library and escorted me into the court building. En route, he said he did condo rehabs for 20 years until the crash of 2008. We entered the courthouse, where nobody ID’d us. We couldn’t find Margaret anywhere.

“How d’you think about what you have here?” I asked.

“An experiment in cooperative living.”

We exited via a rear door. Margaret saw us and flew down a flight of stairs.

“I’m the mayor of the tent city and interface with the law,” Margaret began. “There’s supposed to be a hearing tonight at the request of the landlord but, so far, we’re not invited. I’m trying to prepare for the hearing, find out who asked for it, and get myself invited.”

“But how can there be a landlord? Isn’t this provincial land?” I asked.

“That’s why what we’ve heard makes no sense.”

“What’re you trying to accomplish as tent city lawyer?” I asked.

“It should be legal for us to pitch a tent 24/7 on any public land. People shouldn’t have to be off the premises during daytime. We should be allowed to stay put and create a camp wherever we wish, including city property, without fear of being thrown out.”

Across from where we stood, I saw a man around 35 heading toward us. I wondered what laws we were violating. When he got close, he said, “Hi, Mom. I thought you might want something to eat.” He handed Margaret a bag containing a sandwich and a soft drink. They exchanged words about talking later and he quickly departed.

“That was my son,” she said. “One of three. Between them, they pay $10,000 a month in taxes. They say to me, ‘The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. So, Mom, can you tell us, what’s happened to the tree?’ I tell them, the reason I’m doing this is for my grandkids, so their generation has the right and the choice.”

“How does the community react?” I asked.

“Some people think we’re ignorant. It’s true, there’s infinitely more that we don’t know than we do. So, none of us should ever be offended if somebody calls us ignorant. We just are, nomads and house-dwellers alike.”

“How d’you react to people who say the tent city looks like a refugee camp?” I asked.

“Do people really believe that? Have they seen what real refugee camps look like? As a child, I came to Canada from Germany as a refugee. We were welcomed. I don’t see anyone welcoming new residents to our tent city except ourselves. Nobody’s managing us; we manage ourselves. When conflicts arise, we deal with them democratically. We keep the park area clean. We even look out for passers through.”

“Some people call you socioeconomic refugees,” I said.

“No question, many of us flocked here due to economic displacement and disastrous social support systems. The world hasn’t come to grips yet with the reality that climate change, poverty, and war have made massive migration by refugees the new normal. It hasn’t come to grips with the factors creating chronic homelessness either.

“What exactly d’you want?” I asked.

“Some of us choose to live as nomads. The law should bless our choice.”

Margaret broke off our conversation, saying, “I need to prepare a statement for the hearing tonight, even though we haven’t been invited yet. Feel free to stop by any time. You know my tent. I’ve got heat so we’ll be warm and I always have hot coffee.”

Weeks later, the media reported plans to open two transitional communities to house homeless street people and eliminate need for Super InTent City (SIC). However, because it attracted many of the most marginalized and criminalized—based on drug use, mental illness, and mostly crimes of poverty, such as vagrancy—SIC’s residents were at a competitive disadvantage in gaining admission.

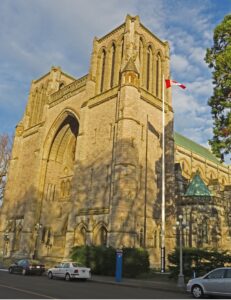

By Christmas, SIC’s population swelled to 120 for the long winter. It continued operating on principles of inclusive diversity, mutual support, and nomadic fluidity. Lean-tos became interspersed among tents. Reps of social service agencies visited almost daily. The Cathedral offered a warm place to escape the coldest days of winter, re-charge cell phones, wash up, and use restrooms. Two of the Cathedral’s deacons participated in talking circles. One wrote an editorial to the effect that the tent city is where Jesus would have hung out.

The prevailing view among the homeless was, “everybody needs a home.” They didn’t want to be institutionalized; they wanted real solutions—permanent, supported, appropriate housing—and no random room checks, no police surveillance, and being allowed to bring in guests. Meanwhile, the unwelcoming NIMBYs wanted the homeless moved out of the neighborhood, preferably out of the city, and housed in what amounted to internment camps.

By Spring, organized opposition increased. Now crowded with lean-tos, the space formerly used for talking circles had been repurposed, and SIC no longer projected the look it had six months earlier. A flame, tended by First Nations residents for sacred purposes, was cited as a fire risk. Police claimed increased area crime. In reality, crime rates citywide decreased, with more stringent enforcement of crimes of poverty (e.g. “unwanted person”) near SIC. In April, Victoria’s housing authority sought an injunction to close SIC. B.C.’s highest court refused, saying SIC “posed no risk of irreparable harm to the city or its residents” and any harm was not as great as the harm that shutting down the tent city would impose on the homeless who found community and safety there. Subsequently, running water and toilet facilities were installed.

In its next salvo, opponents alleged that gangs dealt drugs and operated a bike chop-shop within the tent city. A deacon formally reneged the Cathedral’s support. The city again sought an injunction to close SIC, again claiming fire hazard and increased crime. In reality, these were mostly crimes of poverty resulting from a NIMBY campaign to report unwanted persons to the police. This time BC’s highest court granted an injunction, saying SIC’s residents had to leave as soon as alternative housing was offered, and SIC must irrevocably close by an imminent date.

Although B.C. and Victoria found funds to create new supportive housing and promised the homeless and advocates this supportive housing would be “different,” it turned into the same punitive, heavily-policed sort of shelter so many of the homeless had fled. In a comparable time periods, one person died in SIC, where people took care of each other, but 13 died in supportive housing, where close surveillance prevented mutual support and aid. Although Jane, Mark, and Margaret all entered the shelter, Jane soon found herself evicted to the street after defending the rights of residents, and Mark too left. The last I heard, nomad Margaret was still hanging in, while Jane was living in a tent in the woods with her boyfriend and their dog.

In SIC, the homeless found mutual support and civility. They tried to coexist with their housed neighbors, but there was nothing civil about the response they received, especially from the human rights lawyer who led the charge against them. All the homeless wanted was to be able to live civilly and in community. Several SIC residents subsequently attended a provincial summit about the future of tent cities to house the homeless. At least 90 such tent cities have come and gone in British Columbia in recent years and, like other tent cities throughout the Pacific Northwest, they met similarly uncivil ends.