Only madmen and mystics live without metaphors.

—Patrick Harpur

The story:

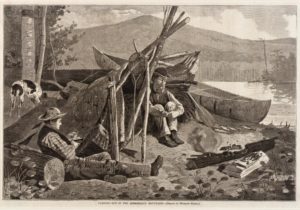

Once upon a sabbatical, a hermit rented a small hut.

He yearned to be a mystic, discover God or,

failing that, learn what it meant to be alone.

Settling in, he found he liked the little tasks

of living, keeping to himself, keeping

silence, keeping sane.

On his walks, he took the woodland trails,

but he wasn’t a thief, he always returned them—

circling the lake, un-circling it.

No snakes to his knowledge (or else very quick).

No knowledge, either. Everything meant

only itself.

Hunting season came and went. He was game;

he stuck it out. Winter followed.

And loneliness.

Soon he was pacing, cursing squirrels,

casting them into outer darkness.

When they kept coming back,

he praised their persistence. Spring

arrived. Then summertime. Time

to return to the world.

The world, he found, had done well

in his absence. He praised

its persistence.

The End.

The exegesis:

The tricky element in every story is the I,

with its iffy implications of integrity or irony.

Should the I prove unreliable, what holds true?

A chalice? Cupped hands? The blue bowl

of heaven? Something must hold true.

God?

God, I’m told, can use a stone as easily as a saint.

Does this make God a Mason? a magician?

a madman? Protagonists, too, are tricky. Take,

our young hermit, is he a stand-in for the body;

our wannabe mystic, a stand-in for the soul?

Together, are the two of them a stand-in for you.

Are you nothing more than a stand-in for me?

Did you think I would know?

So, tell me, are we finished here? Or shall we

rattle on a bit until we hear a voice

praising our persistence, or until

there comes the sound of one God clapping?