a new start, permission to travel,

to shoot the breeze

with someone closer than six feet away,

to be jostled on the street,

in the grocery store—

life, as it was

SISYPHUS is an online magazine that values original thinkers and honest inquiry.

a new start, permission to travel,

to shoot the breeze

with someone closer than six feet away,

to be jostled on the street,

in the grocery store—

life, as it was

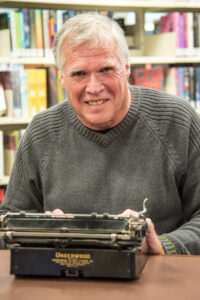

by John Davis

something was amiss.

small tremors sifted sandy soil.

trees took on a slight tilt, listed.

flowers withered in their beds.

the dog gave up barking.

I lost my job.

at first, I was speechless, then garrulous:

speech spotted with dangling prepositions

meaningless elisions and contractions

punctuated by perseveration and Tourette’s.

my wife came down with echolalia.

we both started talking in tongues.

the house, the yard, everything we owned

disappeared, simply dropped into a sink hole

while a mere fifty yards away

people went on washing cars

mowing lawns, pretending

this was simply our lot in life ¾

people who don’t know their grass

from a hole in the ground, who believe

charity and justice are satisfied

with a couple coins in a beggar’s cup.

by Ed Harkness

Isolation: cold word, with ice in its veins,

not to mention that other sound, “shun,”

at the end. I think of all those rhymed

relatives: nation, duration, desolation,

ovulation, creation—dozens

of cousins, those blood relations

bound to us by skeins of sound.

Alone, cut off from you, loves,

there’s not much to do but study

a patch of jonquils, seven in all,

half-hidden by an upturned wheelbarrow

at the corner of the toolshed,

their white sockets frilled, rain-spotted,

splashed by in-and-out sun.

Why have I, after all these years,

only now noticed them? Who,

before we came on the scene,

planted them in this out-of-the-way spot?

In isolation, there can be solace,

even as the dying die alone,

even as the dead have no place

to rest, exhausted by their tribulation.

Then there are the other dead,

the red-caps crammed in the town square

howling approval when the king

waves his rubbery arms, shrugs and grins,

ripping sense from every ruined sentence,

spitting back nonsense to wild applause.

I’m thankful for a certain kind

of solitary confinement, the kind

where we’re close by being far.

Here, then, are seven jonquils.

Here’s sunlight on their flared skirts.

I give you their stillness, their brief lives.

When they nod, I give you the wind.

“The Year of the Plague: A Letter,” first appeared in the inaugural issue of Light, an online literary journal published by Lauren Grosskopf, publisher of Pleasure Boat Studio press.

For a while we caught the spirit of things

as they had drifted in the past. And we got

to know them really well. Cobwebs sailed

above the shore…

–John Ashbery

You know what makes me happy? Bach, and birds.

And children, even when they’re ill-behaved.

I’ve spoken with the parents, and the wind

is dropping by this evening, to appraise

the way grandparents have been tending to

inclement weather, and the rites of spring.

This time around being, like, chaotic. —So

by tallying apart things that we know

to be true, or at least not everywhere

riddled with falsehood, we can just relax.

But if the age of miracles has passed,

it’s back to work for us! Untouched by fire,

it’s going to be more grueling this time.

We’ll wait here for the next storm, for its light.

It seems to me we’re finally “getting” life.

Or living. Which is almost the same thing.

If I get too happy, mix me a drink.

I’ve been reliving old errors: here’s my song.

This time, I’m right. Correct me if I’m wrong.

For Bruce Hopewell (2018)

by Ed Harkness

Two sawhorses, a yard-sale hollow core door—my backyard worktable.

On it, a pawnshop of tools: chop-saw, cat’s paw, level, cordless drill, square,

nail apron in whose pockets are, yes, nails, tape, carpenter’s pencil

and a peach pit. Ear protectors, eye protectors, gloves—all close at hand

for my big project, a dog house. I have no dog. That said, I make a racket:

hammer whacks, the urga-urga of the drill, shrieks of bloody murder from the saw.

In the silent spaces between board cuts, ear protectors tossed aside,

I hear a tiny tapping, rapid fire bursts from a delicate machine gun.

They’re barely audible. Pause. Burst of taps. Pause. Burst of taps.

From where? At which point I notice crumbs of wood float down

from the cherry tree. Of course. Woodpecker, this one a tiny downy,

back of the head red-patched, some thirty feet from where I stand.

He has chiseled in the trunk a hole no larger than a quarter—

excavating a pocket in the very heart of the tree. It so happens

a female downy has just hit town. She clings to the trunk

just above the nest builder. She doesn’t give him the time of day,

pulling disinterestedly at a bit of moss. He taps away. She dashes off

as if the prospects might be better elsewhere. He calls it a day,

then rockets in her direction. That’s how it is. You work at a project

with the tools at hand. You hope someone finds your creation—

a nest in a cherry tree, a doghouse sans dog, a 17-foot tall marble statue

of a naked man with a sling—interesting, worthwhile, a home-made gift

utilitarian or ephemeral, like moonlight on a frog pond. Even now,

in the silent spaces of my life, the young downy chicks having

long since fledged, I hear the delicate taps of a sculptor’s chisel

or a woodpecker at work. It’s creation. It’s what we creatures do.

by Bern Mulvey

The problem with Trump stripping the CDC of COVID-19 data is obvious, but still terrifying. — Sarah Midkiff

Masked, gloved, hood up, I’m eating takeout.

They don’t have to tell us the true numbers.

Coyotes and quail are taking back the streets.

The President says he’s doing great.

They don’t have to tell us the true numbers.

We have an Arizona Department of Economic Security

but the link is down. The President is doing great

as I search for rice and milk and toilet paper.

We have an Arizona Department of Economic Security,

I’m on hold. I pass a lady On the Trump Train

as I search for rice and milk and toilet paper.

She packs a .45 at Sprout’s, no mask, takes the last

Sola Bee Honey, the shirt On the Trump Train

made in China. Like the flash bang grenades

they threw at the Phoenix Free-Speech Zone last

night, the police tape at Surprise Park sparkles

in the sunlight. Just like China, flash grenades

were thrown at us in a Free-Speech zone,

a loud bang, smoke and in the middle sparks.

My mother has been coughing for a week.

Surprise Park has police tape, the kids play zone

closed. Maricopa Public Health is not at their desk.

My mother has been coughing for a week,

the homeless camp on Jefferson is empty.

Maricopa Public Health is away from our desk.

A masked deli man at Albertsons tells me,

the homeless camp on Jefferson is empty,

and the apartments on Grant and 7th burn.

The masked deli man at Albertsons tells me,

I do see a decrease here in the old and sick.

On television, the apartments at Grant and 7th burn,

and Arrowhead Towne Mall has a rabbit nest.

I too see a decrease in the old and sick.

Banner Hospital says they will call me back.

High at the vacant mall lot, I watch a rabbit nest.

Lindsey Graham worries that I won’t work.

Banner’s mobile testing unit will call me back,

coyotes and quail have taken back the streets,

Graham feels I’m disincentived to work,

they don’t have to tell us the true numbers.

Coyotes and quail have taken back the streets.

The President says he’s doing great.

They don’t have to tell us the true numbers.

They don’t have to tell us the true numbers.

by Ed Harkness

Thus, in the florid script of 1870—

ink now well-faded—the census taker

for King County, Washington Territory,

has listed the names on a page titled

“Half-breeds not otherwise counted.”

The names have blurred—a flock of birds

lost in fog. One clear name: “Mathilda,”

age one year. On the line above, Mary,

her mother, 18, surname illegible—

another lost bird. I know these two names.

Thus, in the florid script of 1870

are my kin accounted for, more or less,

in the mundane archives of life on earth,

with its cave paintings, pyramids, gods,

computers, WMDs, self-driving cars.

Somewhere along the line, Mathilda,

now 20, marries a Swede—something Lindstrom,

a fisherman, owner of a skiff in which to skim

the turgid waters of the Duwamish River,

netting sockeyes and silvers when, then,

the river hummed, clear as quartz.

I’ll never know what Mathilda looked like.

Her skin would have been tawny, cedar-

hinted, her hair night-sky dark and thick.

Even at one, her eyes would be hungry,

bright as her Haida mother’s, opened wide

to taste the colors and sounds of the world,

to drink in the new thing called light—

łúkwał, in Lushootseed, a tongue

she may have never learned or heard.

In 1911, Mathilda, dying at 41,

lays herself down on a mat of ferns

on the river shore. She hears the voices

of rocks, trees, the green song of moss

on the alders. She listens to Lindstrom

call to the salmon in Swedish, kom lax,

hears the thunka-thunka of the skiff’s engine,

Lindstrom baling with a coffee tin,

hauling hand-over-hand a net to draw in

his catch, watched over by reeling gulls—

a frenzy of sobs just over his head.

Mathilda dies in the twilight of a slack tide,

not far from Point No-Point. Dying, she hears

the tide turn, hears Lindstrom’s broken whisper,

My darling, must you leave so soon?

Thus, in the florid script of 1870, is Mathilda,

now and for all time, listed on a page titled

“Half-breed not otherwise counted.” I’ve revised

the page to include a one-year-old girl’s eyes,

opened wide to drink in the new thing called light.

Hand me my armadillo mandolin.

I need to sing.

Turn on the Transporter Machine to the moment

shimmering alongside this one.

Somewhere wind is blowing

trailing a wake of sunlight

through a hillside of spring grass.

I see a sailboat leaning

thin as a butterfly

under a bruised sky, so piercingly white

everybody’s stopped on the Embarcadero

peering over their steering wheel

trying to remember where they were going.

The smoke hasn’t gone away

this time, new fires are breaking out,

even in Oregon, and the fire season

is just beginning.

Ash flecks the cars, the leaves,

plumes of it, risen thirty thousand feet,

blocked out the sun, blocked the blue rays,

turned the air Martian orange.

In the City, fog darkens it further,

streetlights are still on. It’s like midnight—

at noon. In the East Bay the sun

is a small, orange disc, a eucharist

rising from the demonic region of civil war,

to hang over the battlefield in the dawn haze,

the weeds and crushed dandelions

beginning to lift, in hesitant, springing upticks,

to waver over the bodies. One soldier is propped up,

as imagined in The Red Badge of Courage,

leaning against a tree as if taking a break,

jaw slack, mouth agape,

ants passing each other along his lips

as if along a window sill. He’s come back to life

on a chair and holding a cardboard sign

next to a crooked blue tent under the overpass.

The air knows what has happened,

the answer no longer blowing in the wind.

It’s in the smoke that doesn’t move.

We’re so divided now, it’s no wonder

civil war comes to mind. What can you do

in this bizarre light and toxic ash

but close the windows?

Going out’s as bad as staying in,

everybody contracted to whatever channel

profits by reinforcing his opinion.

On top of killing the earth

this shit is ruining my poetry.

Our atmosphere of war is appropriate, people

shot in the back by police, most generals

afraid to speak out, dictatorship nearly in place.

Nobody’s in control but a creep,

extolled as the Messiah, by mostly good people

bewildered by neglect and damaged

self-esteem, when what’s

really in control is the burning earth

which is burning

and burning

and even now, I’m about to get in my car

drive across the bridge to meet someone

for coffee. We’re all complicit

in this march toward global extinction.

Inertia is a motherfucker.

Going outside now, the news says,

is like smoking eight cigarettes.

We’re a race of suicidal idiots

conditioned to band together in small groups

that circle each other warily, despise each other,

and we often don’t even know why.

Perhaps we mistake this huddling for love.

Romeo and Juliet are dead,

having dared to love, having finally united

their feuding families, the Capulets

with the hated Montagues, in mutual grief,

by killing themselves.

Where does that leave us,

who are still in love, from different tribes,

still alive, and still needing

fresh air?

The first day of classes

my second-grade year

there were four children

from a family that had

just moved into our school district

in the most remote corner

of west central Arkansas

who showed up barefooted.

I didn’t know why. Sure

they were poor. But we all were poor.

Do not make fun of them

our teacher did not have to say

hardship being something

every student in that one room

schoolhouse understood.

I worried about what they would do

when the weather changed.

But they moved on before

I could find out, following

the harvest, our teacher said.

by Paul Lojeski

My best pal dead almost

four years now, though,

after all this emptiness

I don’t know if we really

knew each other at all.

Connected for four decades

and then some. But time

has done its usual cruel

number on memory and

what was/is real, but

whatever, none of it’s

worth spit this cold, rainy

April night I’m remembering

him. All I know is I miss

his voice flying across the line

over those vast decades

of cosmic movement and

his laugh and mine locked

together, leaping at the sky.

by Ed Harkness

He has arrived earlier than expected,

light as a small bag of apples

in my lap. Now and then he rouses

to blink the black opals of his eyes,

still mostly sightless after all that time

in the dark. I’m his father’s father and—

oh, what the hell—I’m on a short leash,

wondering if my departure will likewise

be earlier than expected—which is,

I suppose, always the case. The future

announces itself as a quiet, insistent

tap at the door. The new being

in the crook of my arm yawns.

Now his lips part in a reflexive dream smile

I take to mean he finds the condition

of being alive curious, wryly amusing,

as if to say, So, where am I exactly?

on this bright November morning,

a day I’ve already subtracted

from the dwindling total. His eyelids flutter,

thinner than the skin of a hatchling robin.

Now I’m reminded babies must eat.

His mother whisks him out of my arms,

off to a rocker in a dark corner,

where, after a few urgent squalls, he’s quiet,

the sucking audible even from across

the room. I’m empty-handed once more,

happy in a way I’ve never been.

I plan to attend his third birthday,

already scripting, after the other kids

have left with their frosting-smeared chins,

the conversation we might have,

the one where I tell him I held him

when he was one day old, his eyes

were exquisite blueberries, different

than the gray-green they are now.

He’ll be only mildly impressed,

more interested instead in tearing off

the paper of one last gift:

a box with a silver latch and key.

He’s wide-eyed to lift the wooden lid,

to get a glimpse of things to come.

I’m more intrigued in learning how

to tie together strings of time,

quilting swatches of months and years,

stitching my life to his, as if I had such power,

the slightest ability to forestall for even

an instant that insistent tap

from arriving sooner than expected.

Still, I’m swaddled in the glory

of the moment, thankful to have held him,

to listen to his mother hum in the dark,

to hear the creak of the rocker

on the hardwood floor.

~Cosmo MacKenzie Harkness,

b. November 5, 2019

Note: This poem first appeared in the inaugural issue of Lights, and online journal published by Pleasure Boat Studio press in March, 2020.

This Indian man is instructing us

about the ways of a native dance,

with illustrations and young people

regaled in their finest beaded clothing

and they sing and pound drums

and the dancers move in ways I have

never seen and the music is notes

I have never heard, like the sound

creek water makes hitting stones under

a distant crow. The man introduces

a new dance and he calls the dancer

by the wrong name and his young

daughter laughs at him just exactly

the way my daughter laughs at me.

A million crows fly over the world

and if we look up we will see a million

silhouettes, each one as different

as Gene Kelly is to these dancers,

but a daughter’s laugh, that,

that sting of wrath wrapped inside

the music of a child’s delight, I

think that’s the same sound

no matter what dance you do,

no matter what creek you hear.

previously published in Galway Review

by Helen Beer

He struggled to find the truth,

but it eluded him. She could

see it reflected in his ever-

shifting eyes; they defied him,

revealed his delusion.

His claim—that his facts were

derived from legitimate sources,

that he didn’t, as she suspected,

glean his talking points from

memes—was laughable.

Point-by-point, he spouted,

nearly verbatim, the talking

points of the far right; he

repeated debunked conspiracy

theories as though gospel.

And she listened, frightened

by the deceit he’d come to

accept, embrace, believe,

regurgitate. But she held

her tongue.

She knew there was nothing

she could say, no data she

could present, no source she

could cite, that wouldn’t be

met with derision, dismissal.

For he was lost in a fog of

lies, and an unquestioning

acceptance of only those beliefs

with which he agreed. He was

steadfast, static, immovable.

And, despite her fear, she was

envious, at times, of his commitment,

of his tribe, of his unwavering

belief, of his alternate reality. And

then she caught herself.

No. I will not dismiss all that

I know, all that I have learned.

No man is worth compromising

my values, my belief system,

my self-respect.

“I can’t do this anymore. I need

you to leave. You’re not good for

me. You’re certainly not good for

my mental health. It’s time for you

to go. Now.”

And then she cast her ballot. For the

first time in four years, she felt

vindicated, powerful. She knew he

would no longer control her every

waking thought. She was free.

I see them running through fields

of waist high grass, chasing sun

between elm islands of shade,

summer bursting in their naked chests.

Orange lilies flame against

dirty white barn sides

decorated with abandoned tires

begging to be rolled down the hill.

Once wrestled from slumber, the sun baked

rubber burns and wobbles under determined hands,

nervous songbirds scatter from its path.

A pause a breath a grunt and heave.

Then shouts of exhilaration

at having done something forbidden

and destructive. The tire, left

where it lands in flattened ryegrass,

will be forgotten, become part of

a landscape it should not belong to.

Filling with the debris

of a dozen snow melts, sheltering

springs of rabbits and winters of rats,

the edges will camouflage

with chickweed and clover.

Yarrow and moss will grow

where once there was mischief and quickness.

And years from now, when this place

seems more dream than memory,

there will still remain

that unchanging wreath

left in memory of a secret between boys.

long stemmed dandelions

bouncing in the meadow

I didn’t notice the bees at first

the weight of each one

pulling down each stem

and letting go

one after another

a field of springing keys

played without sound

I heard a melody

rise from the field—

a death song

a feeling spread through me like water

soundless as dawn

the bees played flower

after flower

going extinct

still singing

POST UPDATE: Sisyphus reader Quantum Kreilkamp has set this poem to music and the author requested the link be shared.

by Mark Bauer

It was a fleeting moment early one Sunday morning on the road in northern Ohio. Such moments always are.

…la rota che tu sempiterni

desiderato, a sé mi fece atteso

con l’armonia che tempere e discerni…

—Paradiso, Canto I

…the vast

wheel you have made eternal by desire

held me intent to hear the harmony

you tune in all its parts…

—trans. Anthony Esolen

I.

The Great Black Swamp is platted farmland now,

drained by a vast, strict grid of ditches spaced

each quarter-mile. From muck rose land to plow,

these quilt-square fields crosshatched with furrows traced

from sluice to sluice in fertile rectitude.

The towns between the Maumee and the Portage

grew flush in times of plenty and renewed

themselves, somehow, in times of shortage.

My last time through I’d grown intrigued and learned

this history. Dawn now: I’ve left the turnpike,

searching for coffee and breakfast, and turned

along a downtown street whose stores stand stern, like

squat, square-shouldered presbyters who ask,

in measured red-brick tones, my business here.

“Sustenance,” I say. And through a mask

of silent shopwindow blinds their answer’s clear:

No lights click on. But up ahead some cars,

American, cushy, vaguely dated,

are clumped outside a diner and a couple bars.

The diner’s Open sign in understated

neon provides the sole sign of life this early.

I enter through the steamed up plate-glass door.

It’s empty but for one booth full of burly,

jovial men; each one of them is more

than half-again as old as I, and I’m

not young. But by their mud-flecked boots I know

Sabbath began some hours ago for them

out in the corn and soybean fields below

a slate-gray sky and fading morning star.

Tucked over in a corner booth, I never

quite catch the quips and stories that they share—

just voices stripped to sound, a wordless river

washing over me, swift waters tumbling in

a rush of glinting, speckling current welling

up, cascading from an origin

far older than the stories they’ve been telling.

Carried downstream, their stories run like silt

scraped up along a broad, brown course from scarp

and bed to settle here as bottomland built

clod by clod, then drained, surveyed, carved up.

They revel in their well-kept stories tossed

around in repetitions recast slightly then

end-stopped by laughs and ricochet guffaws.

These eddy, pool, settle among the men:

Indecipherable to transient eyes

and ears: each story, day, year, generation.

Somehow the repetition sanctifies.

Bring toast as offering, coffee as libation.

II.

The waitress enters, tray in hand. Despite

the hour she moves briskly: soiled plates removed,

glasses refilled, OJ topped off—She’s quite

handy with coffee pots and bowls of grooved

white ampulets of Half-&-Half and packets

of Sweet’n Low. Amiably she glides in

and out; her own contrapuntal banter gets

taken up into the flow as she slides in

another plate. And as their voices blend

another Sunday morning slips in

among these ruddy men, this big-boned blonde.

This blonde: round-faced, apron flapping, wide hips in

snug and faded low-rise blue jeans pie

in slow fan light—and, once and always, someone’s

kin. Their tales, jibes, plates careen, collide

in over-weaving rhythms sprung: Done once

and done a thousand times, she leans and stretches

off across the table wiping milk-dot pearls—

her low-slung jeans and rising top reveal what catches

each man’s eye: A wheel with eagle’s wings unfurled

from hip to hip in blue-green dye. A half-stop’s

silence marks this grace, what these and their folk

half-know between bedsheets, among their crops,

in proper rows in pews: The wheelwork

creaks ahead; each day the escapement ticks

against this mainspring of unbridgeable

nearness; the spring stays wound; these days, these clicks,

this cafe, this winged wheel mean nothing, mean all.

Raise your voice in ache and jubilation:

Bring toast as offering, coffee as libation.

by Diane Ray

ride out the Corona in the saddle of famed hyperbole,

but, seriously, would you call it Splendid Isolation?

If only the only thing to fear were fear itself, or we

didn’t have to fire until we saw the whites of its eyes,

leaving me on patrol priming my radar ears awaiting

my husband’s arriving car post reconnaissance, then

flying downstairs to beat my beloved’s hands to all

the apertures. I intercept the gauntlet– doors, buttons,

knobs. “Welcome home, soldier!” He’s in no mood.

“Go back upstairs! You shouldn’t be down here. I’ve got

this!” My blessed non-obsessive mate, but I know he’s

changing gloves the CDC sanctioned way, then kneels

on newsprint wiping off peril in cellophane which he

believes farfetched but complies to be PC, the abundance

of caution hack, hedge against feeling helpless. I know he

dropped his clothes into a virgin garbage bag when I hear

the tattoo of bare feet streaking upstairs where I lit my

warrior’s way to COVID’s new, nonsectarian Mikvah,

the shower, where he scrubs and purifies post early

morning mission, geezer hour, Whole Foods detail.

———————————————————————————————

Mikvah ritual bathing place for purification according to Jewish law

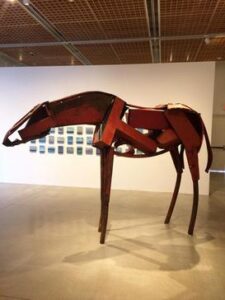

after the sculptures of Deborah Butterfield

In my dream the life-size metal sculpture,

a horse, not solid, but with open spaces,

the connecting curved plates creating

an abstract of the beautiful animal,

the long nose open from crest to muzzle,

belly barrel open too. And yet he

(I knew it was a he, a bay) looked full

of spirit, ready to come to life.

It came to me how we are all

only partially formed and always

in the process of formation,

partially exposed, partially protected.

In children we can see that easily

as they come into being, opening

and closing and opening again.

I’m thinking now about the passage

from the book my husband read to me

last night, just before I slept:

how Jefferson, so long the optimist

concerning the human spirit,

fell into a depression at his life’s end.

And his old friend Adams,

opened into hope at the end of his,

both dying, five hours apart, on July 4.

I’m thinking of the woman on the radio,

called in to quell the rioting kids in the juvenile hall.

They suddenly quieted in their cells

as she whispered, though all could hear,

to the one she knew best on the block,

Jimmy, What’s this about?

When she told the boys stories of the Japanese prison camp

where she’d been held as a child, they listened too

because she opened herself to them.

I’m thinking of my mother,

who became a waitress, then a wife,

then a woman who wanted to die,

and tried, so she was sent to Napa State Hospital,

which she hated. She saw it as the insane asylum.

But then she changed again,

and when she was back home,

baked Christmas cookies,

brought them to the others there,

and was happy

for a while.

I want to ride that horse that’s open and closed,

broken and whole, keep him close to me

so I can remember that always,

even far along the road,

we can learn to be open.

And that sometimes

it is possible

to make our own miracles.

In works of art, just as design choices have both aesthetic and emotional impacts, so too does the absence of design. Ultimately, design also has environmental impacts, which can be brought about either by the materials used in a work or by the presence of the completed work. I was thinking about all of this while writing “The Art of Nothing.”

Two New York artists are vying

over rights to nothing. Both claim

ownership of the idea: a gallery

with empty walls, nothing standing

on the floor. Art historians concur:

the second artist to exhibit nothing

must acknowledge the first.

How about books with pages

not marred by words? Authors

can give readings where everyone sits

in silence for forty-five minutes,

then waits in line for an inscription.

All authors must give credit, of course,

to the first one to publish nothing.

Wikipedia already has a list of silent

musical compositions, starting with

Funeral March for the Obsequies

of a Deaf Man, 1897, by Alphonse Allais.

Why not invisible buildings to end

habitat destruction and global warming

and give the earth back to itself?