“I am an excitable person who only understands life lyrically, musically, in whom feelings are much stronger [than] reason. I am so thirsty for the marvelous that only the marvelous has power over me. Anything I cannot transform into something marvelous, I let go. Reality doesn’t impress me. I only believe in intoxication, in ecstasy, and when ordinary life shackles me, I escape, one way or another. No more walls.” Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell (February 21, 1903 – January 14, 1977)

I’d carefully planned every word I’d say to Anaïs Nin when I first met her. The occasion was the Women’s Celebration at U.C. Berkeley in December 1971—a solo, landmark event for emerging writers. I went to see and photograph the writer who most captured my attention when I’d left my husband and lived alone for the first time in my life, the icon who’d questioned, “How wrong is it for a woman to expect the man to build the world she wants, rather than to create it herself?”

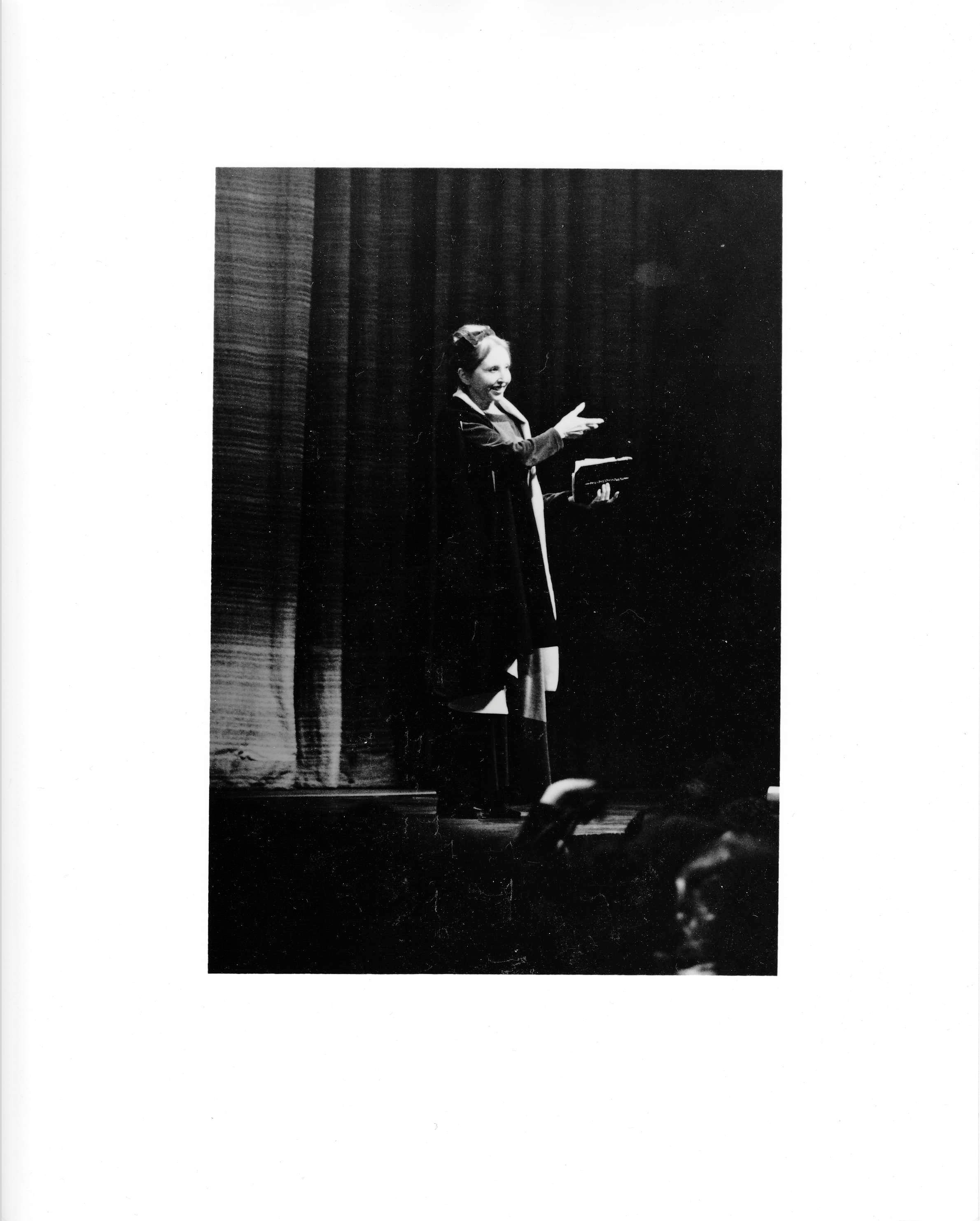

Anaïs floated across the stage in her floor-length red velvet winter gown. She was petite, smaller than I’d imagined, and perfectly formed. Her hands were delicate and en pointe, like the supple dancer she was trained to be, her voice so soft you had to lean in to hear. She spoke graciously, with great care. She reflected before she spoke. She appeared to me French, European. I sprang into action, camera clicking. I took pictures of her as she read, as she spoke, every word elegant and beautiful to my ears. I wondered if any of the two rolls would print well, because I decided to use no flash (at F8 for 1/30th of a second), so as not to disturb her grace. I liked that I didn’t believe in flashbulbs. Like Anaïs, I never wanted to intrude.

One could never imagine her getting angry at anyone. Someone asked if she ever got angry and she responded, “Oh, yes. And then I wait. It goes away.”

I watched her as she introduced the other speakers, her welcoming presence offering them dignity and respect. She smiled with thoughtfulness and wisdom, never shot from the hip, and always praised the best of what others brought to her on stage. “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are,” she advised. I moved to the edge of the stage several times for close-ups.

When the day-long event was over, I waited nervously in queue behind 100 other women also eager to speak to her. After an hour I thought, “Will she leave suddenly, before we can even meet?” I was ready. I practiced in my head: “Anaïs, my name is Donna and I’ve read all of your books.”

But as I reached the author and she smiled up at me, no words came from my mouth. I could not speak when my turn came, not even a whisper. Sensing my anxiety and excitement, Anaïs smiled politely and tried to put me at ease. I remember shaking. She stroked my arm and gently shook my large hand with her softer, smaller one. She’d taken my breath away. She signed my program, in friendship, and I nodded my thanks, believing her, crying the entire time.

She said I must write to her.

After hours in the darkroom, the photographs came out after all. Months later, I chose the best one– a soft focus portrait of her head and neck, her face responsive, all eyes and attentiveness–as she spoke to admirers that previous December. I created an eight-by-ten print with a matte finish on my most expensive Portriga Rapid double-weight paper and mailed it to Anaïs. I included a letter, praising her for her ability to write words that relate to all young women’s struggles to discover themselves. I shared that I was now in psychoanalysis (just like she had been thirty years ago), trying to become who I was meant to be, instead of somebody my family wanted me to be or the person my former husband had ravaged.

Anaïs wrote back immediately, thanked me for the portrait, and asked if I had others. She needed photographs to give her audiences. Could I show her the rest?

After another twenty-four hours in the darkroom, I had five or six more images. I wanted them to be perfect. I still remember sending that package at the Cow Hollow post office on a cold, foggy San Francisco morning before work. I held onto the brown envelope for a minute before dropping it into the mail slot, flipping the handle a few times as if my life were hanging in the balance. Then I waited.

Anaïs’ second letter was full of thanks and—surprise!—a payment, a personal check! She also sent new books, inscribed to Donna, master of light and shadows. I dissolved. I danced. I flew around my apartment, singing, spinning out onto my balcony and telling all the cars lined up to go down Lombard (the crookedest street), “I’m an artist!”

Thus began a correspondence and a job or, rather, a mentorship. Anaïs influenced me in all aspects of my deepest self. I began living in the moment, thoughtfully, not recklessly. I found an Edwardian cottage and decorated it for my taste alone. I took a painting class, another in ballet. Photography and pottery became hobbies. Anaïs used my very first photograph of her on the book jacket of her seventh diary. She asked for many more for stories in the New York Times.

Anaïs invited me to join her writing groups in Los Angeles. I wanted to go, but my psychoanalyst advised against interrupting my therapy. He similarly advised against going to London to study with Anna Freud, when I was accepted at her institute. I complied with his treatment plan, but later wondered about his self-interest. I think he feared I’d become a radical feminist. I became a radical feminist. “Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage,” as Anaïs said.

I enjoyed success at work, was promoted to higher positions. Anaïs had taught we could love many different men, even on the same day, and I dated and explored my sexuality openly. After all, she had husbands on two coasts. It seemed ironic to me when men later criticized Anaïs for the same behaviors they practiced all their lives. I found that this lifestyle had its limits, yet sexual freedom was most exciting for a short time. I came to trust reliable people, work choices, commitments. This was tough in the Seventies when some were enlightened and others were not as thoughtful. Or clear or honest about themselves. Or sober, even.

Our partnership lasted six years, until Anaïs’ death in 1977. At her memorial in Los Angeles, thousands of women spoke about her personal influence on their lives, as the new John Williams quartet played on stage. She wrote to us personally. She encouraged us to consider ourselves as equals. I’ve saved her letters, tied with a purple ribbon, in a small safe. “The role of a writer is not to say what we can all say, but what we are unable to say.”

I continued to work with her second husband Rupert Pole until his death in 2006 and still hear from her publishers occasionally today. Time has passed. In recent years I see a resurgence of interest in Anaïs’ diaries and surreal prose. Whether she remains recognized by the literary world is not as important to me as the effect she had on the women of my generation. She sparked my writing, photography, and clear belief in myself.

Photography classes with Lynette Lehmann and Ruth Bernhard changed my portraits of people. Images became freer, up closer, unabashedly intimate. I began having two- and one-woman shows and joined two art galleries in the subsequent years. Over the last fifteen years of publishing my poetry, I always use my own photographs on my book covers.

People often regard them as watercolors.

Anaïs Nin’s voice was not the edgy language we are told to use today. Hers was the passionate voice of the free spirit, the authentic voice of a liberated heart. I remember waving to her when I happened to be on the seventh floor of a New York City apartment building and she happened to be walking to brunch in the alley below, her publisher beside her. She wore a long black cape that swayed behind her. It was as if she flew, near the ground.