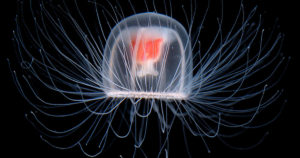

In nature, most things are put to good purpose, little is extraneous, little wasted. Given death’s ubiquity and impact, then, it is difficult to believe that death itself could be a mere accident. Certain species, such as the jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, do not seem to die of aging, only of trauma or disease. They are, except for a bad day, functionally immortal. If these species—although perhaps less daunting in circuitry than a typical mammal—can live forever, then why not we? Some researchers posit that early-life deaths due to trauma and disease relieved evolutionary pressure for immortality against aging. In fact, some species such as salmon, reproduce only in death. Another hypothesis points to finite resources, with death providing the chance for new generations to thrive free of overburdening competition. Death, ironically, is the ancestors’ gift that their progeny might prosper. Religions offer other explanatory lenses for death: the just-desserts of humanity’s sins, the pencils-down phase of a lifelong test, or simply one step (or transformation) along a much broader journey than could be fully understood or experienced from just one life.

It is the last point—transformation—to which my wanderings in nature return me again and again. Invited by a loved one, I recently attended a hypnotherapy workshop that discussed “past lives regression” whereby participants report memories from previous incarnations. Initially, as a scientist of a not-particularly-religious persuasion, I struggled with the concept. Then it hit me: each individual atom of my every molecule has existed for eons. Matter can neither be created nor destroyed. What story would each atom tell? My carbon, my silica, iron, arsenic—where has it been? Have I, in a sense then, not been there, too? Mary Elizabeth Frye’s popular bereavement poem, “Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep,” expresses this idea with poignant flourish, not to be outdone by Carl Sagan’s classic expression: “We are made of star stuff.” One spiritual scientist prefers to think of this continuity in terms of a shared cell lineage, where cell division connects us all, uninterrupted, back through billions of years, as an extension of the first living organism.

Overarching further is the Gaia hypothesis, whereby life and the planet interact to sustain conditions suitable for life—a sort of terra-forming, epitomized in the creation of our oxygenated atmosphere—making Earth a single mega-organism of which we are all part. This lends itself to eco-psychologist Michael Cohen’s concept of Earth as our “other body,” which he demonstrates through a thought experiment drawing parallels between one’s similar emotional responses to one’s own death as to Mother Earth’s. Relatedly, humans (along with several other species), transmit not just the matter that composes us, but also cultures—the teachings of our human ways and of nature. Nature, of course, has much to teach us about death. Matter and love, always recycled, never lost.

I spent my childhood in the rural Appalachian Foothills, among forests far older than I, but mere younglings by a tree’s measure, the posterity of timber. Death, then life, succession. Only one older-growth tree, as far as I could tell, had survived the culls, and my friend and I delighted to discover this gnarled ancient spirit, around whom we could not meet our arms, whose branches bore the nails of generations of children’s dreams. Some years after my father’s passing, I returned home to visit this stately tree but, heartbroken, found it had succumbed to age, its rotting mass stretched on the ground before me now so considerably less imposing, that I angrily wondered whether death had robbed it of its size or my memory had merely inflated it. Just as I was leaving, cursing the fate spared neither my father nor the precious tree, I noticed a young sapling, green and erect, straight from the dead brown bark. Death—life. It was the same realization, recycled, that I had experienced the week my father died. Some days after that personal Armageddon, I remembered that he had cut his hand, smearing blood on the glass door. I went to wipe it off, to save as a memento, but the rains had washed it away. I consoled myself that his blood survived in my veins, but more importantly (I would realize in time), that in me survived everything good about him. Death had burned away all the pain and suffering of his life and, in myself, I had saved all the light—the kindness, the love. And who knows what that iron now nurtures?

Not far from that tree, we would scatter my father’s ashes into a shallow bubbling river running down the Foothills. At the ceremony, a beaver made a fortuitous appearance. I’ve heard several people (my mother among them—red was my father’s favorite color) claim that cardinals are the messengers of passed-on loved ones. I’m not sure from where this folk belief stems, but I delight whenever I see a cardinal. In fact, I hold that most any nature sighting (including plants and aforementioned beaver) is a good omen: at minimum, it makes me smile; a good fortune, indeed, and one I’ve no doubt my forebears would readily visit upon me.

My mother would join my father in the next realm ten years later. That day, I had driven two hours to the mountains, to that golden childhood land in the Foothills. I spent hours there reveling in the cool, crystal winter flows. As I left, I noticed and photographed a tree with a humongous burr—the scar of something catastrophic, something healed—the badge of a wound that could not stop life from thriving.

As we were heading home, I got the call. My mother would have died around the time I had arrived at the forest. Part of me knows she sent me there, knowing that only the river could steel me for the news, that the tree would remind me of my strength. River, before your soft unyielding touch even mountains bow; in your embrace, my heart could never stay a stone. We would eventually scatter some of my mother’s ashes at the river, against the glittering rocky waters, a beautiful white sandy stream, drawn in currents flowing to eternity.

Gazing upon something like a tree, a river, a boulder–feeling the weight of many hundreds, thousands, or millions of years; it is very sobering and calming to behold such wisdom and experience. Much as death provides perspective on what is important then, so too does nature. In its fleeting colors and creatures, in the inexorable advance of its cycles, in its capriciousness, in its splendid grandeur, nature urges that we experience the present, even as it contextualizes—reassures—ourselves as a small but meaningful piece of a much greater scheme that will continue even as our parts of the play move off-screen. Nature reminds that many problems are small, temporary—a flicker of trouble against the billions-years-long global-reaching march of life. Nothing new under the sun.

Time in nature has numerous research-supported benefits for all facets of health, from mental to physical. On top of these general benefits, I think nature helps us, specifically, in our understanding of death. From my own experience, many modern human societies are quite uncomfortable with death—hiding it away behind euphemisms and sterile white walls—in ways that older societies weren’t. In nature, death is visible, omnipresent—but so is life: resilient, ancient, transformative, unexpected. Death, nature whispers, isn’t necessarily something to welcome or seek, but neither to fear. That it is, quite literally, the substrate for life, a mere step along our journey from stardust to what may come. And so too, my parents returned to earth, to become riverbed, a sycamore leaf—to become me, in the best of their ideals, and now you, with the sliver of me you carry now. What ripples are cast and carried by us, long after the pebble is gone?