Navigating the Complicated Realities of Natural Resource Sustainability

Fishing has a long history in my family. Tracings of fish adorn the termite-eaten walls of our summer cottage and my grandpa—as passed down in familial lore—even managed to catch a fish in his swimsuit (unintentionally, he claimed). My dad, never one to be outdone, managed one evening to wrap his line around a bat while fishing off the dock. So it’s perhaps of little surprise that I’ve lately found myself troubled by a fishy proverb that has spawned more offspring than an overripe shad. Give a man a fish, the saying goes, and you’ll feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, however, and you’ll feed him for a lifetime.

At face value, it’s a feel-good quip that cautions against charity and prioritizes the importance of empowerment and process necessary for long-term well-being. As a professor teaching classes about community development, such virtues are easy to cite. That’s the problem. Sometimes, they’re too easy and cliched. Like a bass that has been caught a few times, I’m increasingly reluctant to reach for shiny axioms that tend to oversimplify irreducible realities.

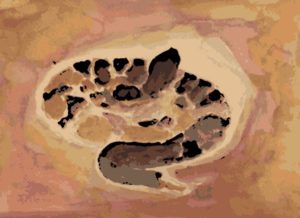

My most memorable encounter with unexpected complexity occurred at the tender age of eleven when, not surprisingly, I had a pole in my hands. Feeling a tug, I reeled in my line only to find a three-inch sunfish on my hook. Frustrated by the endless parade of dinky fish I’d pulled in, this last one having stolen the last of my now extinguished supply of worms, I impulsively cast again, hoping the fish would fly off the hook saving me the time of cutting it loose myself. But the fish held fast and the added weight it leant to my line caused my cast to soar skyward, looping over a branch as it did so. Gravity then brought the fish back down until my spool caught, suspending the startled sunfish just above the surface and only a foot or two from shore. It dangled abstractly for not more than a second when a northern water snake exploded from the shore and latched onto it, thinking perhaps it had caught the first flying fish in Pennsylvania.

Despite my youth I instantly realized I was witnessing something extraordinary. Unsure what to do, I did what came naturally; I reeled in my line. But because the line was looped on an overhanging branch, the fish—and the snake—went straight up into the tree. About midway, with the full four-foot length of the handsome splotchy brown snake now vertically on display, I paused. Unable to let go and with nothing to brace against, the snake was as physically stuck as I was mentally. And even though I was elated to have fulfilled my legacy by being the most recent to snag an unusual catch, I was befuddled as to my next move. The problem was that nothing up to this point had prepared me for this.

In the same way, nothing has prepared our current generation to face the current ecological dilemma. Human population is at an all-time high and still soaring skyward. Over-consumption by western countries shows no sign of abating. Climate change is happening. And resources, be they trout streams or timber stands, are stretched more thinly by the hour. Wes Jackson, author and founder of The Land Institute, wrote that the world follows production at the expense of conservation. He’s absolutely right. And until we reverse this and practice conservation at the expense of production, our natural resources will continue to plummet.

I battle these dystopian thoughts. Like most people, I suspect, I often deal with them by ignoring them. But this rarely works for long. The latest source to sour my day was a recent book by New York Times op-ed columnist Thomas Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree. In a chapter that discusses how globalization can be used for good, Friedman quotes French banker Jacques Attali. Attali, who opted to combat global poverty through micro-finance banking, remarked: “Well, we have millions of poor people who know how to fish. They just don’t have a pole. Through [this banking system], we might be able to get poles for a lot more of them.”

I closed the book and stared out the window, watching chickadees compete at my feeder for the quickly disappearing seeds. According to Attali, the world’s people have learned how to fish. So now it’s simply about getting the right equipment for them. Here was my proverb yet again, this time apparently updated to fit Attali’s thesis. Except the solution failed to address the conservation versus production conundrum. Frustrated anew by this twist, I grabbed my laptop and punched in the original proverb.

Unsurprisingly, the internet was no stranger to the saying, some sources attributing it to Confucius while others argued it emerged much more recently. Whomever the source, and whatever the date, most agreed that if health and independence are the stated goals, then the axiom’s message of enabling people with technical assistance is sage advice indeed. Except that the simplicity of the proverb ignores aspects of resource management, complex agribusiness, and waste management. A few more clicks even got me to my favorite of the saying’s many mutations: “Teach a man to fish and he’ll be dead of mercury poisoning within three years.”

I chuckled, jotted it down, and closed my laptop. The source of my frustration had emerged: goals! The goals of former centuries, with far fewer people and far more disease, were justifiably centered upon attaining better health and more independence. Resources then were diverse and abundant. But today our goals—our singular goal, rather—should be crystallized around sustaining the dwindling resources we have. According to economists, natural resources are the foundation of the world economy. They are critical not only for wealth, but for sustaining life itself. Due to our dependence on clean air, water, and the myriad ecosystem services our resources freely supply, sustaining them must be the goal. And this goal should trump all others.

Whatever you give to the proverbial man, therefore—a fish, a pole, a stick of dynamite, anything—you’ll only feed him for a day if you don’t prioritize the resource. Jacques Attali was right. The world does know how to fish. Fishing isn’t the problem; over-fishing is. Sustaining the resource, rather than independence, health, or modernization, has to be the goal. We may even have to sustain the resource at the expense of other goals.

Sustainably using our resources is more than science; it’s an art, it’s by design. It’s also overtly complicated as each resource is context-dependent, beholden to scads of stakeholders, and often requires a healthy dose of local indigenous knowledge. While general principles may apply, following simple recipes, or proverbs for that matter, won’t work. This, I’m convinced, is the great ecological challenge of our day: how to convey complex sustainability challenges to an audience—the general public, the media, or even my academic classrooms—that have grown up in a culture of sound bites and simplistic sayings.

It was in the midst of standing in front of my stony-eyed students one afternoon this past fall when I edged closer to figuring this out. After class, a taciturn student unexpectedly became my teacher. I had just finished a harangue about Aldo Leopold’s resource conservation ethic, “All ethics so far evolved rest upon a single premise: that the individual is a member of a community of interdependent parts,” (A Sand County Almanac, 1949) and was feeling decidedly like Chicken Little as I dismissed everybody. All the students filed out except Tyler, an avid outdoorsman who was usually soft-spoken and reserved. Today, however, he approached me with a contagious grin.

“I’ve got to show you these!” Tyler said, thrusting his phone in front of my face. “Just scroll,” he instructed. For the next minute, I ogled photo after photo of some of the most gorgeous brook trout I’ve ever seen.

“Where did you catch these?!” I implored.

“Not far from here, on the upper Wiscoy,” Tyler responded. “It’s incredible! I’ll take you if you want.”

“These were in the Wiscoy?” I asked incredulously. Smack in the middle of a large agricultural region in western New York, I had long assumed the Wiscoy was as fouled up as the river it emptied into, the Genesee, one of America’s few rivers that flows north.

“Oh yeah, they’re in there! It’s chock full of ‘em.

“Did you keep any?” I asked.

“Oh, no,” Tyler replied. “Just photos. These fish need to last!” With that, he pocketed his phone and hustled off to another class.

I haven’t yet made it out to verify Tyler’s claims of a rejuvenated Wiscoy. But through just a few photos and some well-timed words, Tyler rejuvenated me. Yes, I was surprised. But I shouldn’t have been. My grandpa had caught a fish in his swimsuit. My dad had reeled in a bat. And I had suspended a snake. Nature is resilient and always full of surprises. Surprises that should give us hope as we tackle complex questions about sustainability.

Tyler’s hope fed me for the day. Once I get out to the Wiscoy, and see those trout myself, perhaps that hope will take root. It’s only the fish themselves that can feed me—and the rest of the world—for a lifetime.

This piece started with a casual conversation with a loquacious ex-military colleague who waxed about the ability to hunt for foxes on certain golf courses in certain states at night. He’s a hunter and relishes any exotic opportunity to do so. From there, the idea grew into a larger notion of wildness, ambition, habitat destruction and the free market dreams of “fixing the environment.” The rest just happens along the way.

This piece started with a casual conversation with a loquacious ex-military colleague who waxed about the ability to hunt for foxes on certain golf courses in certain states at night. He’s a hunter and relishes any exotic opportunity to do so. From there, the idea grew into a larger notion of wildness, ambition, habitat destruction and the free market dreams of “fixing the environment.” The rest just happens along the way.